In previous Emerj articles in the AI Power series, we’ve taken a hard look at AI’s increasing influence both in the macrocosm of our global politics and, more intimately, where it stands to hijack human reward systems through essentially the same forces that drove the ascent of the internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Following each of these trajectories to their most likely conclusion, I’ll begin our current entry with a supposition that might seem bold:

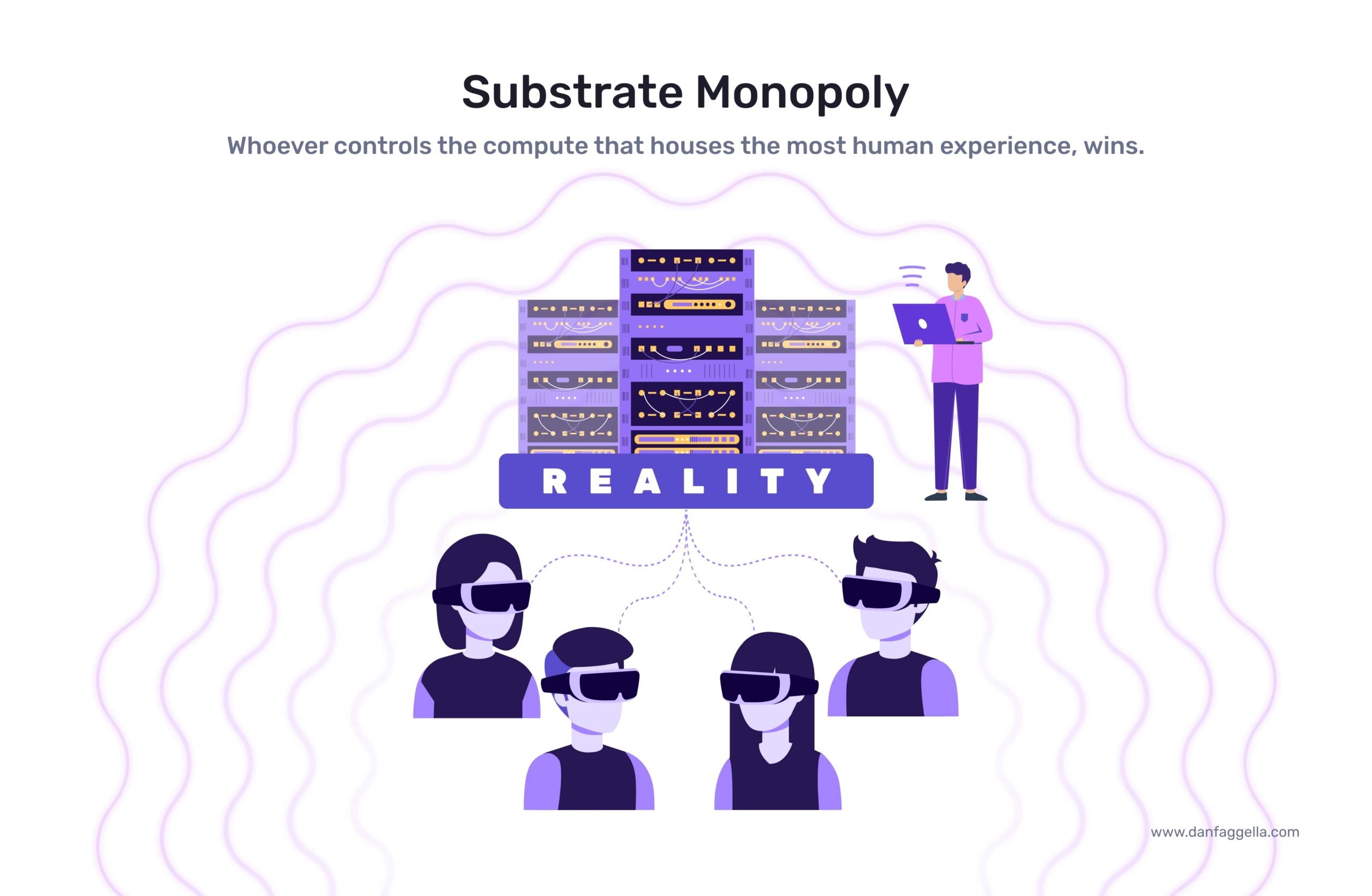

For the remainder of the 21st century, all competition between the world’s most powerful nations or organizations (economic competition, political competition, or military conflict) will be about gaining control over the computational substrate that houses human experience and artificial intelligence.

By “computational substrate that houses human experience,” I specifically mean the servers and computers that host our digital lives – which will eventually become our entire lives (our work, our communications, our records, how we interact with the people we love, etc.). In the present context, the “computational substrate that houses artificial intelligence” then refers to the computers where the algorithms and data are stored and processed to enable AI.

We are not only seeing glimmers of that vision in generative AI use cases from ChatGPT to the astounding text-to-image applications that have taken the internet by storm in the last year but in discussions of emerging AGI (or ‘artificial general intelligence’) – short for describing technological capabilities that far outstrip what we meager humans can contemplate and accomplish.

AGI will likely come to fruition as augmented reality and virtual reality become ubiquitous, and the systems that support these virtual spaces essentially become “worlds” unto themselves, or virtual “places” where people spend most of their time.

As the next decade progresses, we have every reason to believe that our digital reality – where we work, play, and interact with our loved ones – will become preferable to the “real” world. “We are going in,” as I like to say, and the digital world will continue to be more and more prevalent.

Simultaneously, the substrate that makes our brave new digital world possible will eventually become more powerful and coveted than money, electricity, or any single economy on the globe – as it will be the physical residence for how we interact with these domains and anything we value in life.

Given the power that these systems will hold, it stands to reason that whoever controls the substrate – be it a company, country, some other entity, or alliance of these powers – then effectively controls human destiny.

The goal of this article is to estimate both of the following:

- The most likely organizations (public or private) that will be able to achieve AGI and effectively control the substrate of our digital future.

- The likely strategies that these leading power players might enact to secure that control.

In some cases throughout the article, I’ll draw upon quotes and interviews with various experts and leaders in the fields of AI, biology, human political economy, and specialists in the major players in the competition for substrate control.

To tie their insights together in a coherent narrative, I will break down my conclusions into the following subsections:

- Historical power transitions: Taking a high-level look at biological evolution for the last four billion years and the human history we’ve been able to track for the previous 70,000 to draw conclusions about the distinct and objective trends that shape who or what wields control over life on Earth. We will also examine how these dynamics will play into the race to control the digital substrate.

- Players on the field: A comprehensive list of categories for each of the major players in the race for substrate control, from private companies to international governmental organizations.

- Framing the winner: While it is impossible to tell how exactly the power struggle will play out, I will offer my thoughts on the most decisive advantages that certain players will have over others and why those advantages might be insurmountable at some point.

- Policy considerations: In light of our conclusions on who will play and likely win, I will offer ideas on how to shape short-term AGI policy so that the race for substrate control is not concentrated in the hands of a few or nefarious entities.

1. Historical Transitions in Power Paradigms

Power Paradigms in Biological History

Our planet has endured no less than five mass extinction events just over the last 500 million years – a minor fraction of Earth’s four billion-year history. After each mass extinction event, the removal of so many species from their ecosystems in such a short amount of time drives down the competition for resources. What’s left behind are vacant niches, which surviving lineages evolve into.

The surviving lineages – from the tropical marine species that went extinct 365 million years ago to the dinosaurs some 200 million years later and onto human beings today – reflect the successful strategies for intelligence to ascend biological substrate.

Taking an example every American school child knows from the meteor that killed off the dinosaurs, we see these dynamics at play in the rise of mammals and then humanity in their wake:

- The biological life that evolved from a planet buried in ash and covered in methane clouds had to be smaller and agile enough to hide in vacant niches long enough to recover from the meteor’s impact.

- After the smoke cleared, it was open season for evolution to start again – leading to the rise of humanity’s lineage, in which the evolution of our prefrontal cortex gave us dominion over every other species in the span of a few hundred thousand years.

In the context of the race for substrate control, another way of looking at life after the dinosaurs is to conclude that only through mammalian DNA substrate could intelligence re-establish its dominance over the planet. The reptilian and avian substrate that had reigned supreme over Earth for millions of years before still failed to evolve fast enough to escape the fate of the famous meteor that wiped them out.

Power Paradigms in Human History

In human affairs, we see these fundamental dynamics at play in the domains of our technological advancements and the residual effects those changes have on our political economies. In other words, as technologies advance, social structures change as social groups and individuals employ successful strategies to improve their circumstances based on the vacant niches these technologies afford them over competition.

From the technological point of view, it’s less the work of revolutionaries like the American founding fathers or the French proletariat that ended the divine right of monarchs in the 18th and 19th centuries, but rather the emergence of the steam engine. Thanks to steam engines, more people could work, live, produce, market their goods, specialize their skills, and expand their operations without depending on significant waterways that powered the mills of antiquity. Without commerce relying on major waterways, cities became less powerful, and the economic playing field was leveled.

As the Industrial Revolution jettisoned in earnest on the wings of steam power, the importance of industrialists and political elites in the evolving suburban strata usurped that of monarchists in political capital cities throughout the developed world in the 19th century.

Fast forward to today, scientists and historians are already differentiating the “Age of AI” (versus the Digital Age, the Internet Age, and the larger Anthropocene), and it has barely begun. Much of the nomenclature shift concerns the astronomical political and economic power that AI-powered companies, from Google to TikTok, wield over traditional power centers in financial institutions or military contractors.

The bottom line is that a more dynamic competition for control is a product of the hastening pace of technological evolution. For many of us who witnessed the transition from the Industrial Age to the Digital Age with the advancement of personal computer technology and then the internet in the late 20th century, we’ve seen these dynamics play out not over centuries but in just a handful of decades in our lifetime.

The Future Paradigm

The industrial revolution in the UK would have been hard to predict. Why didn’t the Romans get there first, or the Chinese? In biology, the prevalence of crabs would also be hard to predict. Why not eels or bats?

While I’ll leave those answers to historians and biologists, I’ll admit as a technologist that the transitions ahead will be similarly difficult to predict. I won’t be attempting to provide a view into a crystal ball in this article. Instead, I’ll outline some of the likely power dynamics we’ll see in the early transition to an AGI future to flesh out potential ideas about the future.

Let’s start with what we know – or at least our strongest assumptions backed by evidence – about the future.

- The future of ‘Programmatically Generated Everything‘: As I’ve supported in previous articles in the ‘AI Power’ series and tied together in the introduction above, we’re heading into a world where everything we touch, work for, care about, love and hate will not just reside in a digital substrate – but also be generated by that same substrate as well.

- The hardware stack: While our lives may be digitized, the machinery and systems that will house and generate our experiences will remain tethered to physical reality. Simply put, there’s no such thing as software without hardware.

- The transition to the ‘husk’: As human evolution adapts to brain-computer interfaces and a large percentage of First World citizens will spend the majority of their time “plugged in” to the digital realm, they will enter a phase of posthuman transition, I’ll refer to as the ‘husk.’ We see glimmers of the husk in digital identities on social media that far outstrip the influence their authors’ physical identity wields outside the internet.

Given these trajectories, we see humanity on an irrevocable path – or, as I’ve said previously, we’re “going in.” As with many digital trends in the first world, Japan represents the front end of the train in many ways.

From their vantage point, we find a rather frightening vision of what an unregulated, haphazard transition into the husk phase will look like:

- Sexual abstinence and plummeting birthrates:

Birthrates are plummeting in Japan, where the average age is nearly 50. Many Japanese youths and adults – even those with relatively healthy social lives – have little interest in sex or dating and prefer video games and pornography to the awkward world of dating. In a recent study, 30% of the 2,706 men sampled and 26% of the 2,570 female respondents said they were not looking for a relationship.

- Virtual escape:

The Japanese term “Hikikomori” refers to Japan’s numerous (reportedly over a million) shut-ins, usually male, who stay indoors for months at a time – often living with their parents well into their 40s. Hikikomori often have no interaction with other people except through video games or online mediums. I discuss the problem of virtual escape in my previous ‘AI Power’ article on human reward systems.

- Suicide epidemic:

Japan’s suicide rates are staggeringly high. At the 14th highest suicide rate in the world, Japan (like neighboring South Korea) is unique in having such a high suicide rate with such a relatively high per-capita wealth. Most of the rest of the top 15 are taken up by poor Slavic countries.

Parallel trends are easy to find in other similarly wealthy Western countries. Video games in the relatively rich Nordic countries are one example. The opioid crisis in the United States is another example. Plummeting birth rates and reduced frequency of sex among Western youth are probably also symptoms – as well as increasing teen suicide and addiction to social media.

Taken together, the trends all speak to a broader pattern in the First World:

- Countries get rich and gain wealth but don’t gain meaning

- Unhappy people seek gratification through increasingly virtual means

The cycle will eventually continue into a “Great Virtual Escape” that will mark humanity’s transition into the digital substrate I have described. Japan is simply farther along in the transition.

2. The Players on the Field

The major players who will shape the competition for substrate dominance fall into five major categories:

- AI Infrastructure Developers

- Core AGI Models

- End-User Enterprises

- Governments

- Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs)

We will discuss who they are and their strategic advantages and disadvantages in the substrate competition before discussing any educated guesses as to how their interactions will play out.

AI Infrastructure Developers

In referring to the enterprises responsible for developing the hardware infrastructure that will make AI-driven virtual worlds possible, we’re specifically referring to those enterprises that will command access to specific, particularly critical data sources that those AI models will need in ongoing access so they can function correctly.

To clarify the importance of these players, let’s take a step back in time to the California gold rush of the 18th century for a straightforward analogy: One way to get rich quickly in that era was to go to California in search of gold, as many American settlers did. Of course, doing so was still reasonably risky: You’re traveling a long way and don’t know exactly where the gold is, but you’re operating on good information that it’s all over the West Coast.

A much more efficient way to accrue wealth from a gold rush may not be to seek the gold itself but to sell shovels to treasure hunters willing to take those risks. AI infrastructure developers are the shovel-makers of the 21st century AGI gold rush, and their strategic advantages and disadvantages disseminate from their position at the front of said pipeline.

Strategic Advantages:

- As gold seekers will need pickaxes in a gold rush, AI-augmented VR will need data and computing hardware no matter how it looks or operates in the future. These companies may not define the user relationship, but they will be able to shape it from the top of the service funnel.

- No matter how you divvy up the rest of the service funnel, there’s just no escaping the physical necessity of infrastructure and hardware.

- More than the other players on the list, except maybe core AGI Models, AI infrastructure developers can compile benefits in economies of scale regarding GPUs and create a reliable ecosystem that customers trust enough to lock into.

Strategic Disadvantages:

- Infrastructure is essential, but one thing these developers can’t do is provide their own data. Subsequently, it’s impossible to build a worthwhile model without worthwhile amounts of user data – but ultimately, that doesn’t mean data ownership translates to any ownership of the user relationship.

- Collecting data often comes at the user relationship’s expense – otherwise, Meta might still be called Facebook.

- AI infrastructure also cannot compile the benefits of core AGI models unless they own what’s being computed. In typical infrastructure-model relationships in the tech ecosystem, they’re kept far from that ownership.

- There’s a chance that core AGI models can rent hardware or find (perhaps dubiously legal) ways to learn and draw from that rented hardware; doing so renders infrastructure developers out of the substrate competition.

- There also doesn’t seem to be a way for infrastructure developers to benefit from the hardware they create other than to hold it hostage from the other players. They can’t feed off the hardware to harness new technological capabilities. They cannot harvest data to do anything meaningful with it.

Analysis:

- Yes, the shovel-makers in the California gold rush carried less risk and probably slept better at night knowing they had job security, but they didn’t end up with the biggest payout. At the end of the day, risk and reward go hand-in-hand – and in many ways, the competition for substrate domination will be no different.

- There is a possibility that core AGI model players will fight among themselves, and the hardware designer for the winner incurs substantial power riding the winner’s coattails. Still, it’s hard to imagine infrastructure developers getting any farther in the substrate game, given their state of play.

Core AGI Models

At the moment, companies developing core AGI models may seem to hold all the power. Their tools – as evidenced by much of the hype over ChatGPT – appear equally powerful, even for their temporary shortcomings (i.e., “hallucinations”).

However, cracks in the armor have been well revealed by now. Just a few months ago, there was a leak of a memo written by a Google researcher (with the evocative and telling title of “We Have No Moat, and Neither Does OpenAI”) that revealed there is a fundamental problem that core AGI models run into when faced with open source competitors. We’ll discuss these weaknesses below in context.

Strategic Advantages:

- Core AGI models are not easy to build, and once you have a foundational model, you may not have a moat forever (more on this in a moment). Still, you have a sizable moat compared to your direct enterprise competitors for the foreseeable future.

- Equally fleeting is the momentary edge in quality that closed models are enjoying. Again, like the status of their moats long-term, no one expects them to stay ahead in quality for long.

- Because foundational models require so many resources, highly skilled talent, and enormous computing power, successful creators often find themselves uniquely positioned to command a healthy moat of resources.

- Subsequently, the current crop of AGI labs sits well ahead of most competitors in terms of their ability to tap those resources from tech monopolies (i.e., OpenAI’s partnership with Microsoft, as well as ChatGPT’s principal competition from Google’s Bard and other tech heavyweights).

Strategic Disadvantages:

- If core AGI models have a solid user base, they’re worth very little. ChatGPT may have astounded the world in just a few short months, but all of their millions of users still had to access the software through a browser. Without the browser? No access to ChatGPT.

- Framed in such a way, we see core AGI models as being stuck in the middle of the substrate pipeline, which is not a powerful position.

- As foundational models become ubiquitous with open source, everyone can stand on the shoulders of all the radical work that closed LLM models have done in bringing us to the current moment of sweeping AI adoption through the tech ecosystem.

- As discussed widely in Google’s now infamous “We Have No Moat” memo linked above, such was the case when Meta’s LLaMA model was leaked to the public.

- Because of their resources and computing power, core AGI models are big, bulky, and anything but agile. The truism emerging here is that long term, the best models are those which can be easily and quickly reiterated.

- Without the legacy data and customer base, it is much more difficult for newer and open-source players to control user relationships. As with OpenAI’s partnership with Microsoft, they need a partnership with a giant user base – and usually, the abject tech monopolies are the only game in town.

Analysis:

- The current quality moat core AGI models enjoy over open-source iterations is closing quickly. As much was predicted in the leaked Google memo, and we’re already growing noise in OpenAI developer forums that their GPT-4 language model released in March has plummeted in accuracy and functionality in just a few months.

- Perhaps the most damning line in the leaked Google memo is worth spotlighting here: “[Open source model developers] are doing things with $100 and 13 billion parameters that we struggle with at $10 million and 540 billion.”

End-User Companies

If users use your products and interfaces to access core AGI models and their infrastructure, you have sweeping power to hold the entire AI access pipeline hostage. Who are these companies? You might have heard of companies like Apple, Google, Meta, and a small-up-and-comer in the ranks called TikTok that’s popular with teenagers. In all seriousness, there’s even more nuance among these players.

For instance, Apple has gone far out of its way to prove to Meta and the rest that they have the closest end-user relationship through its sweeping features to ensure greater user privacy and controls – all at the expense of any and all attention-driven tech business models. Apple’s management of the App Store landed them in litigation with Epic Games in 2020, who claimed the company’s anti-competitive practices qualified as an illegal monopoly over the market.

Epic may have lost the suit, but Apple’s message to the other players is unmistakable: We’re not messing around, and if you want eyeballs and fingertips, you have to go through us.

Strategic Advantages:

- To state the obvious, Apple, Google, Meta, Amazon, and TikTok dominate how users access the internet. Most roads to anything you want to buy, watch, or read ultimately run through them.

- Not only do they have the users, they have the resources. They can operate at a loss and drive out competition (best exemplified by Amazon), and – likely through their sweeping lobbying and political influence – the arbiters of U.S. antitrust laws don’t seem to have a problem with it.

- If core AGI models want users, they must partner with an abject tech monopoly or one of their also-ran second-tier competitors (i.e., Microsoft and OpenAI’s partnership).

- The most powerful models will require equally powerful computing; for now, only end-user monopolies have those kinds of resources.

- End-user companies can also knee-cap service firms and various model-based applications, as with Apple’s ongoing cold war with Meta over privacy settings.

Strategic Disadvantages:

- Similar to the predicament of AI infrastructure developers and their position at the top of the substrate pipeline, end-user companies’ role in controlling the end of the pipeline makes them powerful, but only to a point. It can command much in negotiation with the other players, but driving a car from the backseat is hard.

- While they have, I would argue, the best seat at the negotiating table given their position – it’s still hard to imagine their dominance outright without wielding direct AGI capabilities or infrastructure themselves. They may gain most of the power but probably have to share a minority stake to maintain their position.

Analysis:

- End-user monopolies can lend their lobbying power to legislative efforts to regulate artificial intelligence through their political connections. Effectively, governments (more on them in a moment) are on their side.

- It will depend on how much they can make their relationship with the user the only relationship that matters in the pipeline. (more on this in “my thoughts,” etc.)

Governments

Fairly self-explanatory, but let’s be explicit and refine the category to nation-states, public sector organizations, and militaries worldwide.

Strategic Advantages:

- There may be no effective end-user monopoly in the great game of life than who owns all the guns. For the time being, those are governments. Let’s also remember the strength of the US and China in unbridled global intelligence and surveillance powers. Even in Western democracies, governments need only jump through some legal hurdles to hack almost any technology.

- While governments are painfully slow in their machinations compared to the private sector, they still are the law. As cumbersome and varyingly ineffective as most regulatory regimes are, they can still work – or cause more headaches when they don’t.

- How many headaches did the US federal government cause TikTok just by talking about banning them? The jury still seems to be out about whether TikTok itself is an arm of the Chinese Communist Party.

Strategic Disadvantages:

- There is an extreme weakness among governments regarding AI talent and fluency, particularly in the West. China also likely shares these weaknesses despite its daft focus on governance.

- Regulation is a slow, blunt instrument that rarely works as intended. For its strengths in inflicting consequences on private sector players, it isn’t easy to know what those consequences will be as regulations are drafted.

- A country that over-regulates its tech sector may impede its ability to compete in the global economy, thus undermining its seat at the table in the substrate game. I would argue that the EU is at risk of doing so now.

Analysis:

- Most of the efficacy of any government to affect the substrate game is wielded by global superpowers like the United States and China. Ultimately it’s their game.

- Unfortunately, the US is barely in the race at all – despite all the military use cases being tested in Ukraine at the moment – and China similarly lags behind.

- With the precedent of the US considering a full-fledged ban of TikTok, it’s easier to imagine a future where perhaps a defense agency would commander a core AGI model and infrastructure as it becomes a threat to nations as the true arbiter of global power.

- Most likely, such a usurpation would come in the form of an agreement rather than a hostile takeover – perhaps a defense contract that an AGI developer ‘could not refuse.’ In China, these usurpations are implicit in the government’s ownership of tech companies.

Intergovernmental Organizations

Let’s just cut to the obvious: No one imagines that IGOs will win the substrate game.

UN Secretary-General Angel Guterres gave a scathing speech in mid-June about the existential risk of AI on the future of the human species. Much like his passionate pleas to reverse the effects of climate change, it’s hard to argue that he’s not telling the truth. That still hasn’t done much to deter global governments from implementing public policy that will affect either problem realistically in the short term.

That said, describing the players in the substrate game isn’t just about which single player is most likely to win but rather, what overall players will ultimately matter in deciding who (or likely, what arrangement of players) will win.

To return to our analysis of power paradigms in human history: the Prussian Empire may not be remembered as commanding anywhere near the power or resources of Napoleonic France or the early 19th-century British Empire. The story of how Napoleon became master of Europe is still impossible to tell without talking about Frederick the Great.

Many cynics and critics argue that the most influential IGOs – the UN, the IMF, etc. – are mere extensions of US and Western hegemony. It still makes sense to list them in their own category for the fundamentally different manner in which they wield (and yield) power in ways neither the United States nor China accomplish on their own.

Strategic Advantages:

- Until recently, trying to get more than 100 countries to agree on anything has been more or less considered impossible in diplomatic circles unless you’re talking about child sex trafficking (and still end up with 44 abstentions in the UN resolution vote).

- A grand exception to the rule arises from the OECD’s efforts to organize a global minimum tax, an effort endorsed by 138 countries. The specifics of the tax itself are not worth dissecting for our purposes other than to say much of it has to do with governments wanting to demonstrate more significant influence over multinational corporations.

- Yet from the precedent alone, it’s easy to imagine 138 countries or more feeling threatened by an emerging AGI competitor and wanting to guarantee their loyalty to the international order in a similar way.

Strategic Weaknesses:

- The global minimum tax is still not a reality just yet, so the rule that getting most of the world to agree on anything is impossible remains logistically unchallenged.

- The perception that many of the largest IGOs are extensions of the US-led world order is much of why their ability to wield tangible global influence is stifled.

Analysis:

- In the coming years, many governments may feel threatened by AI firms and capabilities, providing a stronger incentive to address the problem through IGOs. Doing so will only preserve their market share of global political power, however futile that might be in the long term.

- AI is a fundamentally different issue from climate change and childhood poverty in terms of how it will determine the way nation-states wield political power.

- Many governments sustain their power from the influence of fossil fuel regimes, thus having no incentive to address climate change while maintaining their strength. UN Secretary-General Angel Guterres is very clear about the nature of the problem in his addresses on climate change.

- If we can all agree that the ‘monopoly’ part of the prospect of substrate monopoly is the most dangerous to human quality of life, IGOs will likely be crucial in disseminating and “democratizing” the power of AGI systems. I will detail more on the subject in our final section on policy considerations.

3. Substrate Power Over Time

So who – or what arrangement of players – will win the substrate game? In so many words, whoever can wield the most control over end-users in the substrate likely has the largest say in the winner.

If you’ve been paying close attention to my analysis of the players, the end-user companies category seems especially well-positioned. Whether that is Google, Meta, Amazon, or a competitor will matter in the emerging relationship between AGI and the end-user.

We’re still far from knowing what that system will look like or what logo it will wear. The point is that whoever can provide the best medium for fulfilling human reward systems – pleasure, power, entertainment, or even labor – will no doubt be the most popular, regardless of what exact hardware they are using.

It is reasonable to assume that whoever can achieve maximum personalization in these systems the fastest, especially since personalization of ordinary online systems today is already a robust AI use case across industries.

For whatever concerns there are about the shortening IP moat of foundational models with impending lawsuits from content creators demanding compensation from generative AI leaders that trained their models on their copyrighted works, it’s hard to imagine property or privacy law extending into the human brain.

Core AGI model developers will bank on that lack of regulation as a gateway for the future strength of their systems. At this point, they will not only be able to scrape data from the web and access proprietary data sources at high prices but track the very fundamental activity of human intelligence through their networks.

4. Policy Considerations

AGI policy is challenging because it belies a few dynamics in how we think about our freedom and rights in a future increasingly dismissive of personal privacy as we’ve known it for a few millennia.

For what we might lament in the West regarding these transitions, we must remember the lessons of power transitions from biological history to human history and onto a posthuman future. Or in other words, the meteor that killed off the dinosaurs also gave mammals enough time to proliferate, speciate, and evolve into homo sapiens.

A few general suggestions seem pertinent:

- AGI policy must be global and insulated from the dangers of true monopoly or too narrow a power concentration.

- To such an end, IGOs deserve a more prominent seat at the table for serving as that arbiter. In many ways, the OECD global minimum tax proposal gives us the most precise picture of what that dissemination might look like, for better or worse: slow, reactionary, and outright punitive to the most significant players – but that’s what brings the global powers together.

- There will need to be a more overt effort to counter the advantages that totalitarian regimes will have in consolidating the power of prospective AGI systems and using them for their distinct

The next step is to ask ourselves what global, fundamentally “democratic” AGI will look like.

At such a juncture, it becomes much more difficult to talk about AGI without resorting to strict polarities of any utopian-to-dystopian spectrum. Admittedly, talking about husks and brain-computer interfaces doesn’t feel much to anyone like democracy, especially given what these renderings look like in science fiction and pop culture (I probably don’t need to mention The Matrix).

Still, I would remind ourselves of our earliest version of Western democracy and where it began: as a direct descendent of Ancient Greek theater.

We should also think of theater as the great ancestor – not only of our freedoms and our ability to envision the perspectives of others in an environment that prioritizes empathy above all else – but for the substrate future we see on the horizon. What I’ve referred to as ‘Programmatically Generated Everything’ is merely a theater-of-the-mind concept taken to its logical extreme.

In light of the history I’m highlighting here, it’s worth asking what about the ‘analog’ historical theater lends itself to a societal ground floor of fundamental rights and shared values that will be most challenging for a digital theater-of-the-mind to foster in the same way.

First and foremost, that challenge appears to be that the trajectory of AGI is continued and intense isolation of individuals. In the ‘analog’ theater, you’re experiencing the performance on almost the same terms as everyone else. You’re laughing together and may have different seats, but the rest of the production should be meant to counteract that imbalance if it is well-produced.

As we have seen in the last two decades of social media proliferation and culminating with trends I have described in previous subsections on where Japan is going, artificial communion and companionship are likely to be robust, front-door use cases to a substrate future. Much of that concerns how much social isolation is a distinct feature of Western societies.

If you’re a single aging male in a society like Japan, or even just an everyday user of dating apps – where only the top 5% of males receive 80% of the attention from female users – it may be easier to rely on glorified chatbots as friends and romantic partners than to engage in the manual labor of connecting with humans in physical environments.

Communities and relationships are at the heart of seeing yourself as equal with your fellow hominid citizens of any society. As artificial companions and communities become dominant, AGI policy should focus on the following:

- Ensuring virtual environments developed by core AGI models make critical distinctions between artificial and hominid avatars traversing their spaces. We are far from the point in these capabilities where we need to ask ourselves about AI sentience, autonomy, and natural rights in proximity to hominids.

- Until we reach that bridge, we need to make global, democratic AGI systems serve homo sapiens – at least until we’re ready to “hand over the baton.”

At such a point of my comparison to ancient Greek theater, I’m wondering how much it would help if such systems were a way that not only a digital sense of global democracy could be secured but also enacted.

Ancient Greek theaters were also courtrooms as well as places for juries and assemblies to congregate. Actors displayed passionate performances and athletes competed in the same arena where political power was exercised in the full view of the Athenian public.

If we challenge ourselves to envision ways AGI and VR worlds can help connect us rather than separate us, we may find ourselves asking ourselves some admittedly utopian questions along the same lines:

What if such systems could be the proper platform to democratize IGOs? What if the International Criminal Court could make decisions with the considerations of everyday people as jurors from across the globe through such a system?

If we went a more extreme, utopian step further and asked: What might a global voting system look like that could provide a meaningful check, perhaps a simple veto power, on so-called Western-dominated IGOs like the UN and OECD? It may look a lot like a global VR simulation, where systems that are finely tuned to human preferences will be essential for relaying those preferences in a global political context.

Call that a pie-in-the-sky vision, but with dystopia so much easier to imagine given the offset, we have the ethical responsibility to prioritize even our most hopelessly hopeful visions of the future.

And is it really that unrealistic? At a time when monopolistic players openly admit they don’t have much of an advantage given open-source players, as in the now-infamous Google memo? A leveled playing field for developers may be a feature of bespoke AGI models, as end-user companies’ pre-existing tech dominance might be a feature in how these players can play the game.

More to my point: democratizing these systems will depend on their ability to put tangible, global political-economic power in the hands of everyday people. Democratic systems – digital, AGI, or analog – can’t just be places where everyone happens to be equal; they need to be systems that beget the same equality as part of their innate function.