We interviewed Karine Perset, from the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation in France about the informational pillars that make up strong AI governance for governments worldwide. She offered us numerous insights into how the OECD developed the AI Principles and works with governing bodies to design policies that will keep AI safe and trustworthy into the future.

Additionally, we discuss which types of policies are necessary for which types of AI software as well as the scale at which these policies should govern. This could range from city to city at the local level as well as an international level as governments around the world continue to work on global standards for AI governance.

AI Principles from Karine Perset’s Perspective

In our interview with Perset, we focused on the differences between local, international, and global policies for AI systems and products. There are many considerations for this issue especially with how many different types of AI need to be considered, however there can be no single correct answer to this. Instead, Perset explained how the OECD works to make these decisions while considering the following questions:

- Which policies and legislation should stay local, and which should be global?

- What is the purpose of starting with AI principles?

- What will progress look like on the practical level of AI governance?

Listen to the full interview with Karine:

Subscribe to our AI in Business Podcast with your favorite podcast service:

Which policies and legislation should stay local, and which should become global?

There is a need for international cooperation for creating AI governance much like early 2000 for the internet and the digital economy in general. Many AI vendors and their clients operate internationally, and so any AI system they deploy will have an international or possible global effect. Additionally, these companies need stable and predictable policy environments at the international level so they can reliably create solutions they know they can use anywhere.

The OECD has been working on their first phase of creating new international and global precedents through AI governance, and this includes collaborative brainstorming with the countries and governing bodies they work with. This first phase is about developing common visions between countries and the OECD of how we want AI to help us as humans, boost growth, and stand up to global threats such as climate change. To the OECD, this is equally as important as finding common values that governments across the world want AI systems to respect. This is because they are trying to build as many resources and examples of success as possible for governments to refer to when building policy for their own country.

Part is this vision is recognizing the need for AI systems to provide an inclusive benefit to everyone affected. This goes hand in hand with the need for these systems to respect human rights, and be fair, transparent, explainable, and secure. The OECD is working on this with national governments, corporate stakeholders, and some representatives within civil society to drive this focus into the future.

When asked about where global AI governance is aiming currently, Perset said:

“In May last year, the OECD members and many partner countries adopted the OECD AI Principles, and … a month later the G20 also adopted the same AI principles which is very important because this provides the beginning of a globally policy and ethical benchmark if you consider just the geographic breadth and the economic role of the G20 countries.”

The G20 consists of the European Union and the governments of 19 nations including Canada, China, and India. Hopefully, the adoption of the OECD’s principles will help other nations recognize the importance of AI governance and lead them to greater levels of public safety.

Since the G20 adoption of these AI principles, the OECD has been working on identifying the practices and policies needed to implement those visions. In particular, the OECD established an OECD Network of Experts on AI (ONE AI) early 2020 to provide expert input about policy, technical and business topics related to OECD analytical work. The network includes representatives from government, civil society, the private sector, trade unions, the technical community, and academia. ONE AI is focusing on:

- Developing a user-friendly “classification” framework to help policymakers understand the different policy considerations associated with different types of AI systems;

- Identifying practical guidance and shared procedural approaches to help AI actors and decision-makers implement effective, efficient and fair policies for trustworthy AI (i.e. AI that is inclusive; respects human rights and is unbiased/fair; transparent and explainable; robust, secure and safe; and accountable);

- Developing practical guidance to help implement national AI policies for: investing in AI R&D; fostering data, infrastructure, technologies, & knowledge for AI; shaping institutional, policy and legal frameworks to promote AI innovation, including through experimentation, oversight and assessment; d) building skills and preparing for labor market transformation, and co-operating internationally. The network also facilitates information exchange and collaboration between the OECD and other international initiatives and organisations focusing on AI, including the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI), the European Commission, the Council of Europe, the United Nations and some of its specialized agencies like UNESCO, the International Standards Organization, OpenAI, and the Partnership on AI (PAI) among others.

In some cases, these practices will start in specific areas of greater AI impact and will help build an example base that will inform broader policy and legislation in the future. As policies are seen to work at the local and domestic level, they can be emulated elsewhere and possibly expanded to the international levels.

Currently, there are not any general regulatory instruments that are specific for AI either at the national or international level. However, several governmental bodies are exploring whether existing laws and regulations could be adapted or whether new regulation is necessary, and if so, in which specific cases. Consultations are taking place at the European level. Other regulatory interventions span from bans and moratoriums (on lethal weapons, deepfakes, facial recognition systems), to testbeds and regulatory sandboxes, and certification programs. One example is the country of Belgium, which has prohibited the use of any autonomous lethal weapons by their local armed forces.

Additionally, there is significant experimentation happening at the local level with autonomous vehicles. Some regions have legalized the use of public roads as a “living lab” for autonomous vehicles, such as California. However there will still be obstacles keeping AI companies from instrumenting their products at a global level even with these considerations. For example, an autonomous car manufacturer will need access to Australian road data in order to properly train a machine learning model to recognize the idiosyncrasies of Australian roads such as kangaroo crossing.

Perhaps surprisingly, France has provided another example of this type of experimentation. The French minister of the digital economy has recently declared that France wants to experiment with facial recognition before deciding on how exactly to limit it on the city and national levels. Some European countries are more commonly known to be risk-averse when it comes to the risks associated with new technologies, but this is beginning to change.

In parallel, governments are issuing guidance and are considering practical implementation guidelines for the use of AI systems, including in government. For example, The United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has produced guidance for organisations on explaining decisions made with AI, guidance on AI and data protection, as well as an Auditing Framework for Artificial Intelligence. New Zealand’s Government recently published its Algorithm Charter for Aotearoa New Zealand to guide the use of algorithms by its agencies.

What is the purpose of beginning with AI principles?

The OECD has developed their set of AI principles so that countries can build policy frameworks and legal infrastructure that are coherent with an international standard and with best practices. From there, good practices of each country can be identified so that governments can understand the lessons their peers have learned and emulate policies that have been effective elsewhere. They intend to help create the foundation on which strong and specific AI policy is built so that countries around the world can leverage the tremendous good that the technology can bring while also creating solidarity around risks and safeguards for using the technology in the future.

The OECD hopes to help motivate more countries to join them by acting as an exemplary organization for promoting AI-powered growth and innovation while addressing economic, social and ethical risks associated with AI. This will hopefully lead countries to adopt their AI principles or similar policy foundations that will help them get a handle of AI governance and prepare their country and people to benefit from AI. The next step for a country that does this will be to work on national AI policies and partnerships with relevant organizations to achieve their specific AI-related goals.

What will progress look like on the practical level of AI governance?

As AI technologies become more broadly capable, the need for local, national, and global AI governance will change to attempt to understand those new capabilities. Ideally, this new power can help governments benchmark progress, and identify the best policy options to achieve a specific goal before designing policies. Depending on the extent to which a powerful AI system becomes a challenge, the policies around it may need to be expanded internationally or globally.

When talking about how local policies are identified and expanded internationally or globally, Perset said:

“In the same way that environmental policies or tax regimes [sometimes] require global governance, those AI systems that have local impact will require local governance and those that have a global impact will require global response.”

Some of the challenges that powerful AI systems can raise have already been identified, such as risks to democratic values. AI-powered surveillance systems could violate human rights without the proper accountability mechanisms. Another concern is if market concentration becomes so high that corporations could pose a challenge to governments in terms of access to skills, AI talent, and competition. This could compound growing public fear of labor displacement as AI changes – and perhaps accelerates – the tasks that can be automated. Policies are needed to accompany the transition to an AI economy, both to build new skills and accompany displaced workers. Without such systems in place, there is a possibility of disruption and turbulence in labor markets as technology outpaces organisational adaptation that could result in political and economic consequences that are hard to predict.

Many AI policies that begin locally or nationally carry useful lessons internationally both in terms both of opportunities and of mitigating risks, underscoring the importance of countries sharing their stories and experiences with one another. For this reason, the OECD is building the evidence base to help inform policies by monitoring and analyzing participating countries and how their experiments may help each other’s research.

AI Research at the OECD

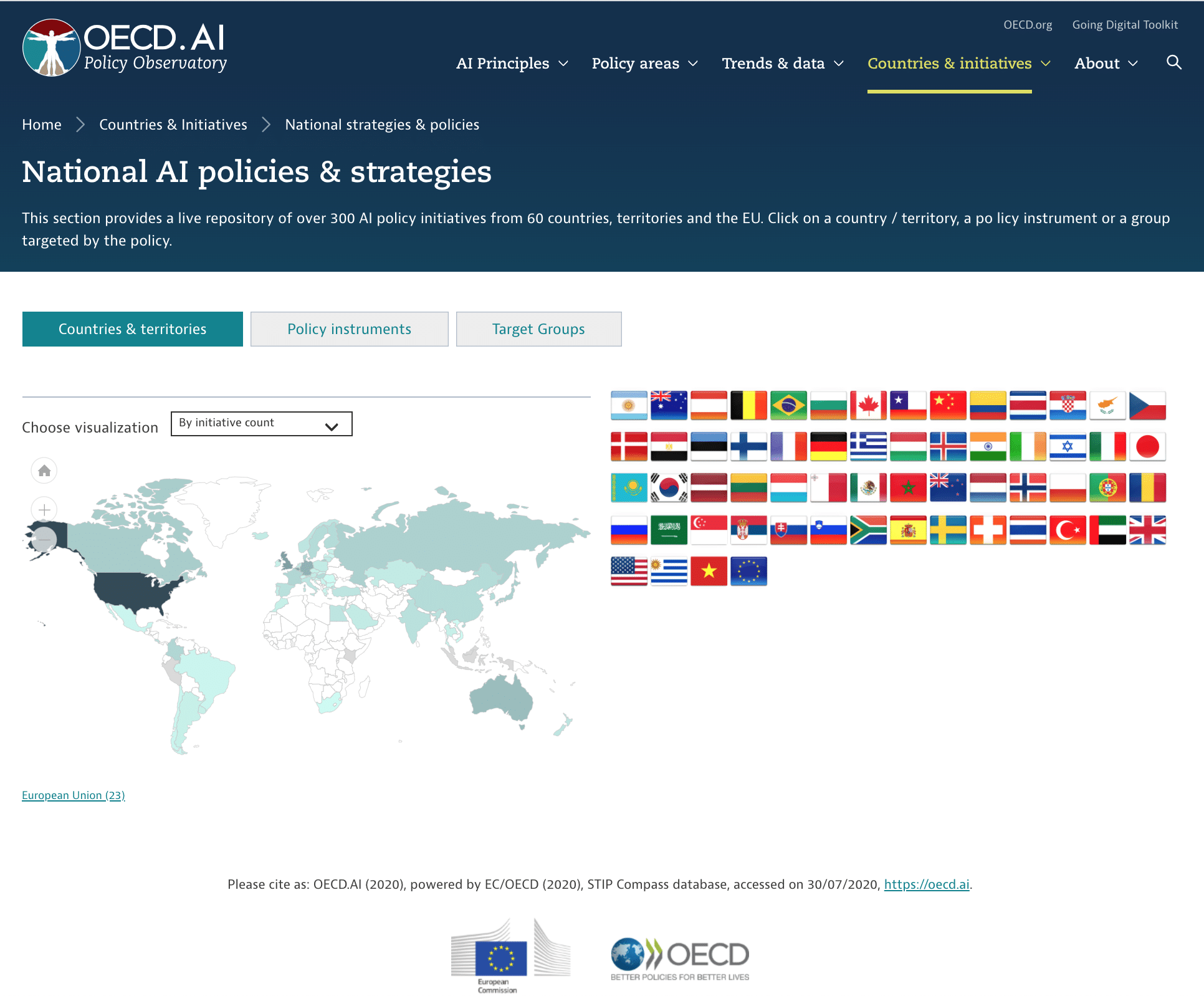

The OECD has created an AI Policy Observatory. Here, readers and researchers can investigate the governmental policies concerning AI across the world, and what types of initiatives are currently underway. Two of the main pillars of this observatory are called “Countries and Initiatives,” and “Trends and Data” respectively. We believe these pillars to be invaluable resources on what is happening in AI governance now and how governing bodies have made it to their current policy positions historically.

Countries and Initiatives

This pillar of the AI Policy Observatory focuses on the political initiatives surrounding AI across OECD member countries. One can organize the countries according to how many active initiatives are currently being pursued as well as by the range of their budgets. The U.S. has one of the highest initiatives counts at 36, while the United Kingdom and the Russian Federation have some of the widest budget ranges. If a user clicks on a country or its AaaaqqaD BBC they will be brought to a corresponding page that shows all of the OECD’s data on that country’s initiatives, a live feed of relevant AI policy-related news data, and a list of their current initiatives and what they are.

Below is an image of the OECD’s interactive map showing each country highlighted according to their number of active initiatives:

Ideally, this tool could be used by policy-makers across the globe to help them get a sense of what is going on in AI regarding their area of politics. They can use examples from political initiatives from other countries to show their peers possible ways forward and why their own ideas may work. Additional access to live news data might help newcomers get a sense of what is important right now as well as areas they should work on to build a foundation.

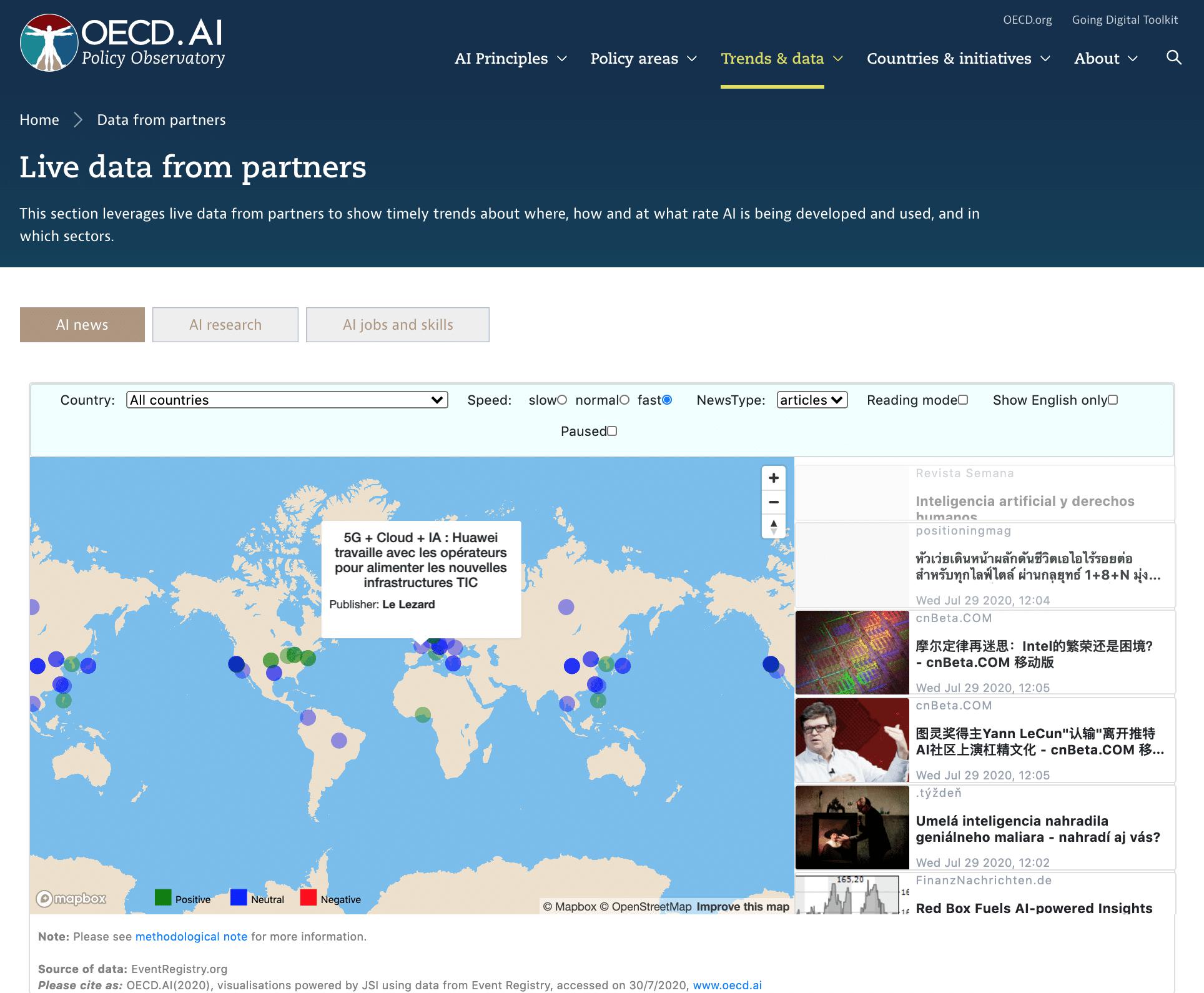

Trends and Data

The OECD’s collection of trends and data are valuable for those who want to predict the next big wave of AI innovation and start thinking of ways to create policy around it before the demand for it rises. Their collection of live data from OECD partners like the Slovenian Josef Stefan Institute, Microsoft Research and LinkedIn allows readers to investigate how much AI research is going on in other countries, how AI jobs and skill requirements are developing, and how people with these skill sets migrate between countries.

Below is one example of the trends and data section, where the user can see a live feed of news updates next to an easily navigable map. If the user clicks “AI research,” or “AI jobs and skills,” they will be able to see data relating to the previous country they were viewing:

While it is likely the live AI news section helps to inform the OECD’s trends and data, the tool itself may be more useful for those who are tasked with more ground-level research which they bring to their superiors who may be legislators or policymakers. This is because the news map acts as a portal to myriad articles as they are published across the world, but they are not immediately categorized and listed in a way that a decision-maker might easily parse. We hope that those interested will explore the OECD website (including their new AI Wonk policy blog) in more depth, as there is undoubtedly a plethora of important policy information that could help them make their next move legally or within the enterprise.