Several car makers predict they will able to make true self-driving cars in the next few years – as we’ve covered in our recent self-driving car timeline article. This technology, though, is only valuable if there are plenty of roads these self-driving cars are legally allowed to travel on. Even if the technologies allow for true autonomy, without legal permission the self-driving cars are mostly worthless to individuals and companies.

Even if the industry does manage to overcome the numerous technical challenges required to make cars capable of safely driving themselves (which remains a real technical challenge), that doesn’t assure that the technology will see massive deployment once they do. The industry will also need to deal with legal, behavioral, and economic challenges before we reach a point where self-driving cars can be ubiquitous.

This article examines several of the biggest non-technical challenges self-driving cars could face and how the industry hopes to overcome these issues. Most of these hurdles are intertwined in complex ways, but for simplicity this article will break down the challenges into two main categories:

- The human behavior challenges, which include how people often misuse technology or are scared by change.

- The legal challenges, which include issues like regulatory restrictions, political blowback, and special interest lobbying concerns.

When we get self-driving cars “depends more on political factors than on technological factors” Hod Lipson, Professor of Engineering at Columbia University, and co-author of DRIVERLESS: Intelligent Cars and the Road Ahead told Emerj. Lipson says the technology is getting better at an exponential, “But law and policy isn’t keeping pace… Until governments sets a clear and simple goal, companies don’t know what to aim for and consumer don’t know what to expect.”

To understand the non-technical hurdles autonomous vehicles will face first requires an understanding of how the technology will be used and categorized.

What Self-Driving even Means

The Society of Automotive Engineers defines a vehicle’s autonomous capacity on a scale of 0-5. They are effectively:

- Level 0 – No Automation

- Level 1 – Driver Assistance – Basic driver assistance like automatic braking.

- Level 2 – Partial Automation – Advanced driver assistance like cruise control combined with automatic lane centering, but the human driver needs to monitor conditions at all times.

- Level 3 – Conditional Automation – Under specific conditions the car can drive itself, but a human driver needs to be ready to quickly respond to a request to intervene.

- Level 4 – High Automation – The vehicle is capable of safely driving itself without ever needing to request a human to intervene, but it can only drive itself under specific conditions/pre-mapped territories (such as a mapped downtown area).

- Level 5 – Full Automation – The vehicle can drive itself anywhere under any conditions.

The technical challenges involved in creating a car that can drive itself in every conceivable environment and under every condition means we will not likely see true Level 5 autonomy for a while. For example, Volvo’s autonomous car AI has more difficulty predicting the hopping movement of kangaroos than the running movement of most other mammals — a problem they have spent years trying to solve.

Instead, Level 2, Level 3, and Level 4 autonomy are what we are currently seeing and are likely to see in the near future. The problem is that anytime that you include humans in the process, you create room for human error. There are several ways this human involvement can created unique technical and legal problems.

Autonomous Vehicle Regulations – Issues of Human Behavior

The Hand-Off Problem

In theory, a car with a Level 2 or Level 3 system that can automatically perform 90 percent of all important driving tasks and automatically avoid most accidents would be much safer than a car without one, but in practice it doesn’t exactly work this way.

Humans are easily distracted, and it takes them several seconds to mentally switch from one task to another, which could mean life or death when driving at 70 mph. Unless a person is constantly involved in the driving process, it is easy for them to become, bored, highly distracted or even fall asleep.

A system that is good enough but not yet perfect can lull individuals into a false sense of security, resulting in a catastrophic failure. This means Level 2 and Level 3 systems require a way to keep drivers alert and readily engaged when they have nothing to do, which in practice is no easy task. Ford tried everything including lights, loud noises, vibrations, and even a copilot to keep their engineers engaged during testing, and none of it worked.

A real life example of a driver being lulled into a false sense of security may have occurred on May 7, 2016 in a fatal crash involving a Tesla Model S. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) investigation found that the car was in Autopilot mode (Level 2 technology) when it collided with a tractor trailer.

Even though the trailer “should have been visible to the Tesla driver for at least seven seconds prior to impact,” the driver took no action to avoid it. This likely indicates the driver was not paying attention, despite Tesla’s explicit warnings to drivers about the limitations of their Autopilot system and their use of built-in systems to keep drivers alert.

This hand-off issue is so bad companies like Ford, Volvo, and Waymo have decided to effectively avoid Level 3 cars all together. Even the car companies that are pursuing Level 3 are dramatically limiting their use. For example, Audi claims their new Traffic Jam Pilot is Level 3, but drivers can only use it when stuck in very slow traffic on limited-access, divided highways.

Liability

This hand-off problem also raises a legal liability issue. If an accident is caused by a car with zero automation, the driver is obviously to blame. Similarly, if a vehicle completely under AI control causes an accident, the liability would fall on the car marker/software provider. Google (now Waymo), Mercedes, and Volvo have said they would accept liability for their autonomous systems.

Who exactly is liable, though if a Level 2 or Level 3 vehicle gets in an accident? If the car warns a driver but the driver doesn’t react in time, is the car or the driver at fault? What is an appropriate amount of time and level of warning before a hand off? We might imagine that this kind of an issue would be even more concerning with larger, heavier self-driving trucks.

These are questions without an easy answer or even one answer. Liability laws and legal precedent vary significantly from country to country and even from state to state. Without national regulation, there are no real guidelines for how possible cases might be decided. Moreover, given the technology is so new, there are few existing lawsuits to look at.

Common laws is based on judicial precedent. Decision by high courts on new legal issues effective bind lower courts and give anyone an expectation of how laws will be enforce. Until a body of cases involve these technology work their way through the courts it is unknown how the judiciary will treat these liability issues.

Fearing What’s New and Unknown

In general, people have an irrational fear of new dangers and become too complacent about established dangers. This can be a problem for self-driving cars.

Take, for example, this fatal Tesla crash in Florida. It was covered by a number of media outlets including the New York Times, the Guardian, Reuters, and the Washington Post.

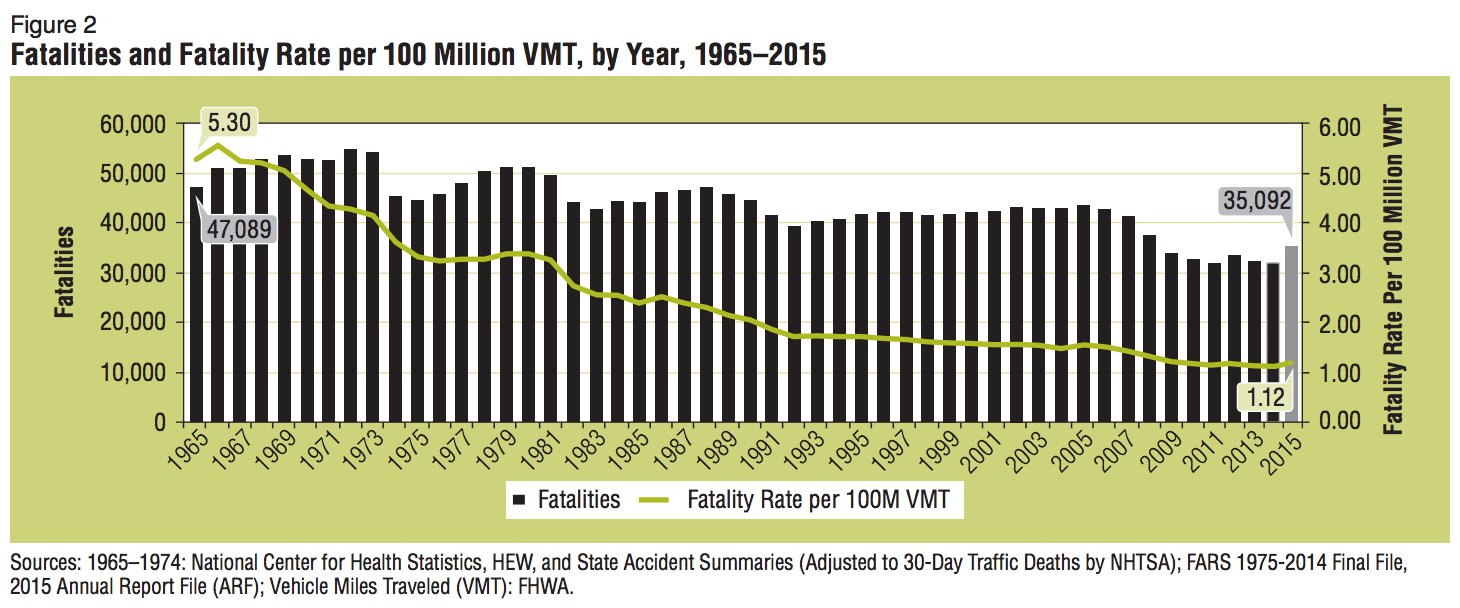

Now consider that, according to the NHTSA, just over 35,000 people died in roadway crashes in 2015. That means on May 7, 2016, when Joshua Brown was killed in the Tesla accident, roughly 100 other people likely died in regular car accidents. None of these other normal traffic deaths generated anywhere near the level of national and international press since they weren’t unexpected or new.

This disproportionate media focus on any death involving an autonomous car will likely continue, and there will be more deaths. According to the NHTSA, 94 percent of accidents are caused by human error — so while theoretically perfect self-driving cars can eliminate most accidents, even they won’t stop all of them. While rare, there are always going to be problems (like freak rock slides, or deer jumping into the road) that probably can’t be avoided.

Heavy media attention around autonomous vehicle accidents and irrational fear can make individuals more scared of something new than they should be based on the statistics. This can create a political environment that is more difficult for new regulation.

Autonomous Vehicle Regulations – The Legal Challenges

The legal hurdles that might slow the deployment of autonomous cars are numerous but can be divided into two areas. On one hand, bureaucracy often moves slower than technology changes. On the other hand is the political considerations.

Even if an administration nominally supports the technology, public agencies are required to be diligent in writing new regulations. Additionally, legislators often have more pressing issues to take up than bills about a technology that may or may not actually exist in the future.

Regulatory Patchwork

The United States’ federal agencies are, at the moment, very supportive of self-driving car technology, but they admit they currently don’t have the regulatory structure or statutory authority necessary to make it work. In self-driving car guidelines issued last year, the Department of Transportation wrote:

The more effective use of NHTSA’s existing regulatory tools will help to expedite the safe introduction and regulation of new HAVs. However, because today’s governing statutes and regulations were developed when HAVs were only a remote notion, those tools may not be sufficient to ensure that HAVs are introduced safely, and to realize the full safety promise of new technologies.

The paper highlights several places where the Department of Transportation would potentially need new legislation such as pre-market approval and cease-and-desist powers.

While the department continues to let states experiment with self-driving car regulations as they work on their own rules, they acknowledge it is not a good long-term solution. The department points out the goal must be for manufacturers to be able to focus on one standard instead of “50 different versions to meet individual state requirements.”

Congress has begun work on a bipartisan effort to fix this patchwork problem by giving the department the authority it needs to set national rules that pre-empt current state laws. There is no guarantee when or if Congress will get to it, given their busy legislative calendar full of more pressing issues. The industry has been wise to aggressive push for these regulatory changes well in advance of when they expect to make use of them.

Until federal action is taken, the growing patchwork of state laws will remain a mess. Currently, 20 states have adopted their own autonomous vehicle laws, and three states have executive orders on the subject. While these varying state laws have been useful for helping companies’ testing, they could hinder actual commercial deployment.

Political Problems

American regulators and legislators are fairly pro-autonomous vehicles at the moment, but political opposition could emerge to actively slow or stop the process. Lobbying groups, such as taxi drivers or airlines, might oppose the technology as a direct competitor. Similarly, landowners and businesses in certain areas may be legitimately concerned about how changing commuting patterns would impact their land value.

There are roughly 1.8 million heavy truck drivers, 1.3 million delivery truck drivers, 660,000 bus drivers and 230,000 taxi drivers/chauffeurs in this country. That is a lot of people who could lose their jobs due to the technology and create a political backlash.

India’s highways minister Nitin Gadkari recently claimed India won’t allow self driving cars because, “We won’t allow any technology that takes away jobs.” He might not be the only politician to take that position once the technology starts being used.

Even the United States is no stranger to laws that prevent automation from eliminating totally unnecessary jobs. To protect jobs, Oregon and New Jersey still don’t allow individuals to pump their own gas.

“It is going to be very ugly,” Vivek Wadhwa distinguished fellow at Carnegie Mellon University and author of The Driver in the Driverless Car: How Our Technology Choices Will Create the Future told Emerj. With some many jobs at stake and so many big changes likely to result for self-driving cars, “there are going to be [regulatory] battles everywhere.” Both at the national level worldwide and big fights state by state. While Wadhwa believes “technology will win out in the end,” these fights could slow the roll out of technology in many places.

It is worth noting that the first country to really let a company experiment with self-driving taxis on their roads was Singapore, a city-state which aggressively discourages car ownership and driving — making it a country were the possible political impact of autonomous vehicles is likely to be very limited.

Beyond employment concerns, people might irrationally fear the technology is unsafe, be upset that it gives rich people some advantage, believe that “zombie cars” will cause traffic downtown, dislike them for aesthetic reasons, or just hate change.

Polling by AAA found 54 percent say they would feel less safe sharing the road with autonomous cars, and 78 percent would be afraid to ride in one. These are fears any organization which would financially be hard by the widespread use of the technology could exploit to slow it down or stop it.

Intel, which is a major producer of self-driving car components, understand this is potential consumer and political problem. It has been doing extensive focus group research on the ways to best make people comfortable with the technology.

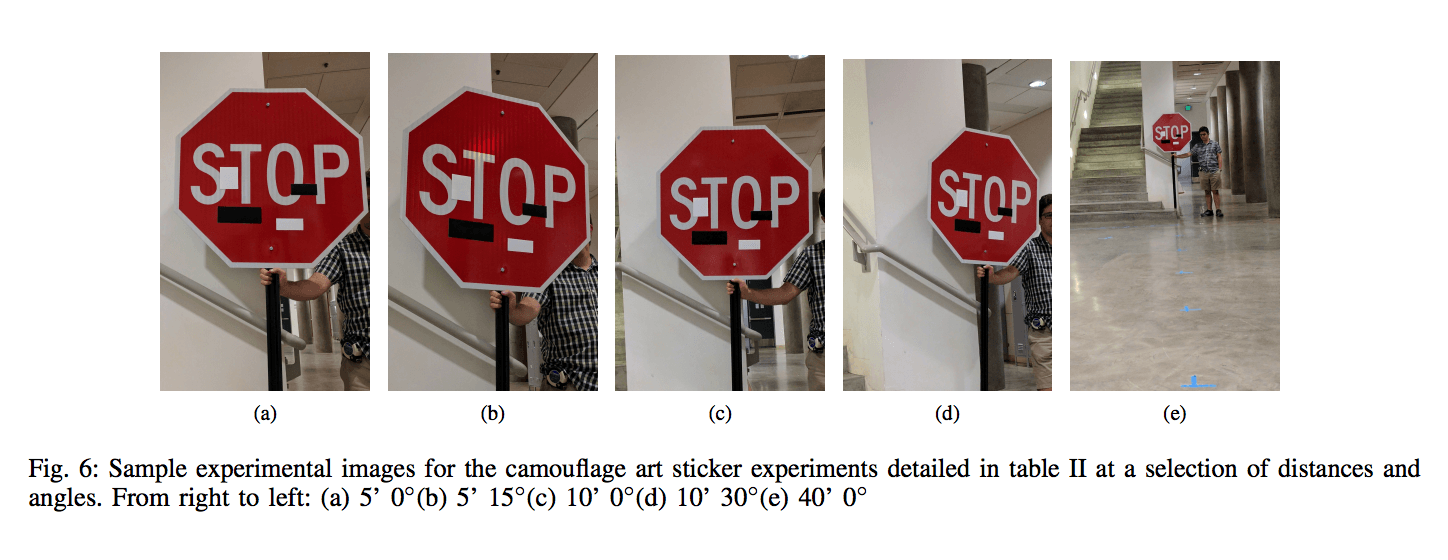

While most people probably think of telephones as a great technological advancement, back in the 1880’s many groups actively fought against putting in telephone lines as blight. In some cities police cut down poles and people threatened to tar and feather workers installing them. The opposition was short lived but intense. Researchers found that it would be easy for disgruntled individuals to mess with current self-driving car AI. A simple graffiti can making traffic signs unrecognizable their vision systems.

Conclusion

The way car makers and technology companies have been aggressively investing in autonomous vehicles leaves the strong impression they expect Level 4 self-driving cars to be a rapidly adopted and transformative technology. Theoretically, big improvements in safety, convenience, and efficiency would on net make society better off, so the technology should be appealing.

However, self-driving cars will only see massive deployment in countries where the government allows them on the roads. In a democracy, getting that approval requires the right political environment. For example countries where fewer people hold driving based occupations might be more politically receptive to the technology

The issue is that at least in the beginning, the benefits for most people would likely seem modest and nebulous. At the same time, for the millions at risk of losing their jobs, the downside would likely feel huge and immediate. Even when the side that benefits vastly outnumbers the side that is losing, losers can have a disproportionate impact on policy when they are more motivated.

For example, in the United States the penny has so little value it cost the taxpayers more to make one than they one is worth. Pennies are a net drain on the government. Yet since the benefits of getting rid of are rather diffuse, zinc companies have effectively lobbied for year to continue their production. Zinc is the main component of pennies.

Exploiting the public’s current fear and skepticism, lobbying groups that might lose out from autonomous vehicles could generate some real traction if the technology ever starts making a real impact.

For now the economic impact debate is mostly theoretical, so it is smart that the potential autonomous car markers are pushing for the legislative and regulatory changes they need while the issue is mostly ignored. At the moment, is it going rather smoothly but that could change when the autonomous rubber meets the road and people start losing their jobs.