While in previous decades military unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) were very simple pieces of equipment, the technology has advanced rapidly. They are now used all over the world and are a multi-billion dollar industry. According to the Teal Group, current worldwide military UAV production stands at around $2.8 billion, and they project it will grow to $9.4 billion in 2025.

The Center for a New American Security and Bard College do their best to document the use of drones around the world. Yet obviously, since military development is often a closely kept national security secret, there are limitations to what they can find out. From their data we currently know there are at least 150 different military drone systems being used by 48 countries. Drones range in size from the hummingbird size Black Hornet mini-copter to the massive 15,000-pound RQ-4 Global Hawk.

In 2001 the United States became the first country to use a true armed drone in combat. Now there are at least 28 countries with armed drones in their military, and we know at least nine (the United States, Israel, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Iran, Turkey, and Azerbaijan) have actually used them in operations. Six of those countries only first used an armed drone in just the last two years.

This article will look at three countries heavily involved in developing and producing military UAV: The United States, Israel, and China. For each country, we’ve done our best to cover:

- The most cutting-edge current UAVs in the USA, Israel, and China

- The role of artificial intelligence in the UAV applications

- How UAV-related industries are impacting the international market

One important aspect to keep in mind whenever talking about military technology development is that almost all countries have top secret programs. While it is possible to get a good sense of where things stand based on public data, the picture will always be incomplete.

(For readers who are interested in the broad range of non-military drone applications, please see our full article “Industrial Drone Applications”.)

UAVs in The United States

The United States is by far the largest researcher, producer, and user of military drones. The Teal Group projects that the United States will account for 77% of total military worldwide research, development, test & evaluation (RDT&E) spending on UAVs in the coming decade and just over half of all military procurement.

The most recent military budget request called for $2.4 billion to be spent on research, upgrades, and procurement of unmanned aerial systems. The single biggest item is $1.2 billion for the MQ-9 Reaper, which is the primary offensive strike drone for the United States military.

The MQ-9 Reaper is built by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems and the latest in their line of the Predator®-series. This drone has a top speed of 240 KTAS, a maximum altitude of 50,000 ft., can carry a 3,750 pound payload, and can operate for 27 hours. Each is equipped with advanced infrared sensors, cameras, laser range finders, and several possible ordinances. They can be controlled remotely or fly autonomously. According to General Atomics, as of last year its Predator-series vehicles clocked a total of four million flight hours.

A highly sophisticated MQ-9 Reaper costs around $14.5 million per airframe, but the unit cost of the cheapest manned F-35 is still $94.6 million. Military drones are cheaper than planes, cheaper to operate, can operate longer, and may soon be better at combat.

Psibernetix – an Ohio-based artificial intelligence company – has developed a fuzzy logic AI they named ALPHA. They claim their AI now easily bests highly trained pilots in simulated aerial combat where opposing plane try to shoot each other down. This AI has not officially been deployed in any military system, but it indicates what can be theoretically done and may be done in the near future.

Perhaps the single most telling data point showing just how dramatically armed drones are changing the nature of American air power is the impact they’ve had on Air Force pilot allotment. The Air Force now has more pilot positions for operating Predator-series drones than any other type of pilot position. The Department of Defense projects that by 2035 unmanned or optionally manned vehicles will make up 70 percent of its entire fleet.

America is a leader in the use of armed drones, but it also uses a wide range of UAVs, from the massive to the tiny, for surveillance. One of the Pentagon’s efforts to always improve its surveillance capacity is the development of tiny and relatively inexpensive Perdix drones. These drones have been undergoing testing for the past few years.

Unlike large remote-controlled drones that can perform autonomous functions, these cheap AI drones operate entirely autonomously using swarm intelligence. The swarm stays in constant communication with itself and changes its configuration to complete the mission if any one drone is lost.

The idea is to have a swarm over a battlefield with the drones automatically positioning themselves so they collectively have line of sight coverage of every raise, depression, or possible hiding space in the landscape. This would allow them to perform highly detailed surveillance or use their coverage to jam communications.

It is not surprising that completely autonomous drones are being used first for surveillance and communication. There are safety, moral, and legal reasons to want people still in the loop for any weapons system, but surveillance raises fewer ethical issues.

While America is the dominant user and developer of UAVs, its role as an exporter of these systems is relatively limited thanks to laws restricting their sales. That might change in the future as President Trump recently launched a review of these restrictions.

The rise of drones has also created the need for the development of anti-drone systems. Anti-UAV Defense Systems are being deployed by United States forces to counter small drones being used by rebel groups. The US military also recently contracted with Syracuse Research Corp. to build anti-UAV systems with spatial, frequency, and optical surveillance capabilities to detect drones and then disable them with jamming equipment.

(For readers with a broader interest in military applications beyond gliders and drones, see our full overview article on military robotics applications.)

UAVs in Israel

The state of Israel is believed to be the largest military UAV exporter in the world. According to a 2013 report from Frost & Sullivan estimates that Israel’s UAS export revenue totaled $4.62 billion from 2005 to 2012. Israel and other countries often don’t say exactly how much military equipment they buy or sell so estimates often merely inferred from numerous sources.

Israel owes this dominant position to a few important factors. First, Israel had some of the earliest uses of UAVs for surveillance. Second, as a small country surrounded by hostile powers it has a highly developed defense industry which often focuses on technology as a force multiplier. Third, the long reluctance of the United States to share its drone technology created a clear market opportunity.

Reporting indicates the Israeli military has more than 100 drones, and they account for around 70 percent of the Air Force’s flying time.

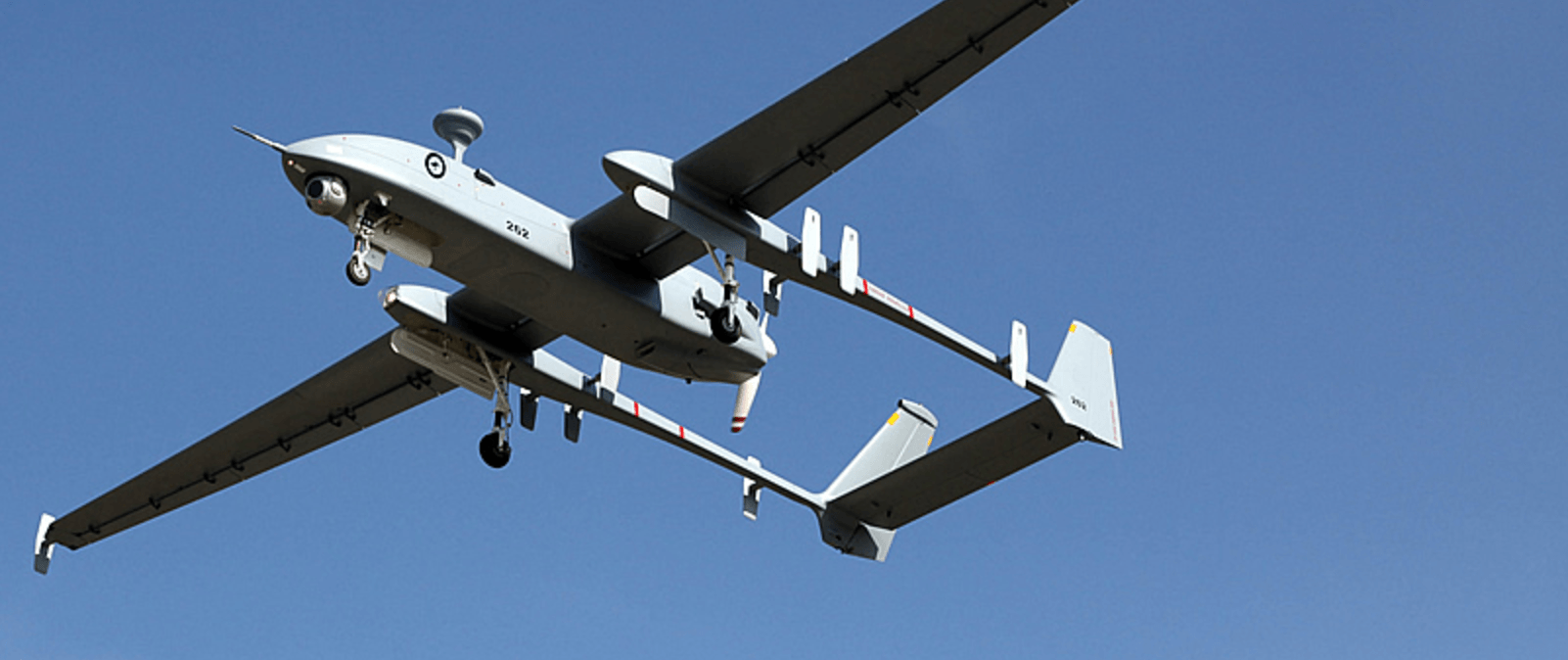

One of the country’s leading UAV makers is the state-owned Israel Aerospace Industries, which produces the Heron family of drones. The Super Heron can fly for up to 45 hours, has a top speed of over 150 kTAS, and it has a wide spectrum of sensors. It is equipped with an Autonomous Flight and Automatic Take Off and Landing (ATOL) system. Versions of the Heron have been exported to numerous countries around the world with India being a major customer.

Israel is also a major innovator in anti-drone systems. Israeli defense contractor Rafael recently announced the launch of their “Drone Dome.” It is a radar-based system which can identify targets and use a laser to neutralize them from several kilometers away. It is a natural progression of Rafael’s Iron Dome system to intercept rockets and artillery shells.

UAVs in China

China has the largest army on the planet by personnel numbers and the second highest military budget behind the United States. The country has rapidly become an increased user of drones for its own military and an exporter of these systems to other countries. China has particularly found a market for their UAV among countries that for political reasons would prefer not to buying from Israel and don’t meet the United States’ tight requirements for export.

For example, earlier this year Saudi Arabia announced it had reached a deal with China to build a military UAV factory in Saudi Arabia. While details are limited, it could be one of the largest international drone deals to date. China is a major source of drones for countries in Africa and the Middle East.

China recently claimed that the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation is ready to start mass producing the Cai Hong 5 (CH-5), the country’s most advanced publicly acknowledged drone. They claim the CH-5 is equal to the MQ-9 Reaper in technology, although specifications indicate it has a weaker engine. It is said to be able to operate for 60 hours and fly at 30,000 ft.

The Chinese government is rather tight lipped about how exactly it is using and plans to use AI for its military, but it has made clear it sees heavy investment AI as critical to the country’s future and will be used to “maintain national security.” The Chinese military seeks to capitalize on the future of autonomous warfare and use its growing civilian AI development to help do so.

For example, earlier this year China Electronics Technology Group Corporation claimed to have launched a record-breaking intelligent drone swarm with 119 UAVs. They claim the drones were flown with ad hoc networks and under autonomous group control, but they have provided no information on when or where this test took place.

The United States shares China’s belief that their focus on AI will have broad military implications. Chinese companies have been making large investments in American AI companies, and the United States government is weighing whether to further restrict these investments to prevent technological transfer.

Concluding Thoughts on Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

Major and minor militaries around the world see UAVs as the future of airpower. In 2015 the United States Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus said the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter will likely be “the last manned strike fighter aircraft the Department of the Navy will ever buy or fly,” and that autonomous unmanned vehicles will be the “new normal in ever-increasing areas.”

Drones already make up a large share of vehicles in operation in major militaries and the percent of airpower and flight hours they make up in air forces is expected to grow significantly. As a result, the market for drones is projected to increase several fold in the coming decade with the United States, Israel, and China playing a major role.

The United States’ massive military budget and long history of cutting edge military research effectively guarantees it will be a major source of military UAV spending and investment. The United States’ restrictions on military equipment sales, though, means Israel and China will continue to play a big role in the international market.

Governments are heavily focused on using AI to improve drones’ flight performance and surveillance information processing, but exactly how they are planning to use the technology is mostly kept secret (we’ve written recently about machine learning applications for satellite imagery, and it’s increasingly likely that militaries will be using UAV camera data for similar computer vision-aided surveillance and reconnoissance). The fact that it is a closely guarded secret, though, does point to the high value certain governments place on its development in this field. At least one area that is likely to see real deployment in the coming years is the use of swarm intelligence to have hundreds of small drones taking surveillance role currently being filled by large UAVs.

The market for military UAVs, the AI technology flying them, the sensors that power them, the programs that process the massive amount of visual data they collect, and systems that allow them to connect to satellites/ground forces will all grow. Market Focus projects the global military AUV market to grow at a compound annual growth rate 38.7 percent between 2016-2022.

The growing use of UAV by militaries and rebel groups also means that there should be a corresponding increase in demand for anti-UAV technology.

Header image credit: Defense Industry Daily