Within the rapidly growing field of brain-computer interface (BCI) research, we have already begun to see devices that can help amputees control prosthetic limbs and paraplegics move their hands and arms just by thinking, but the latest BCI research involves giving speech to patients who are unable to voluntarily vocalize.

Edward Chang, a neurosurgeon at the University of California, San Francisco, is developing a BCI that he hopes will give a voice to the speechless. According to a report in Discover Magazine, the wireless device could translate brain signals into speech by means of a voice synthesizer.

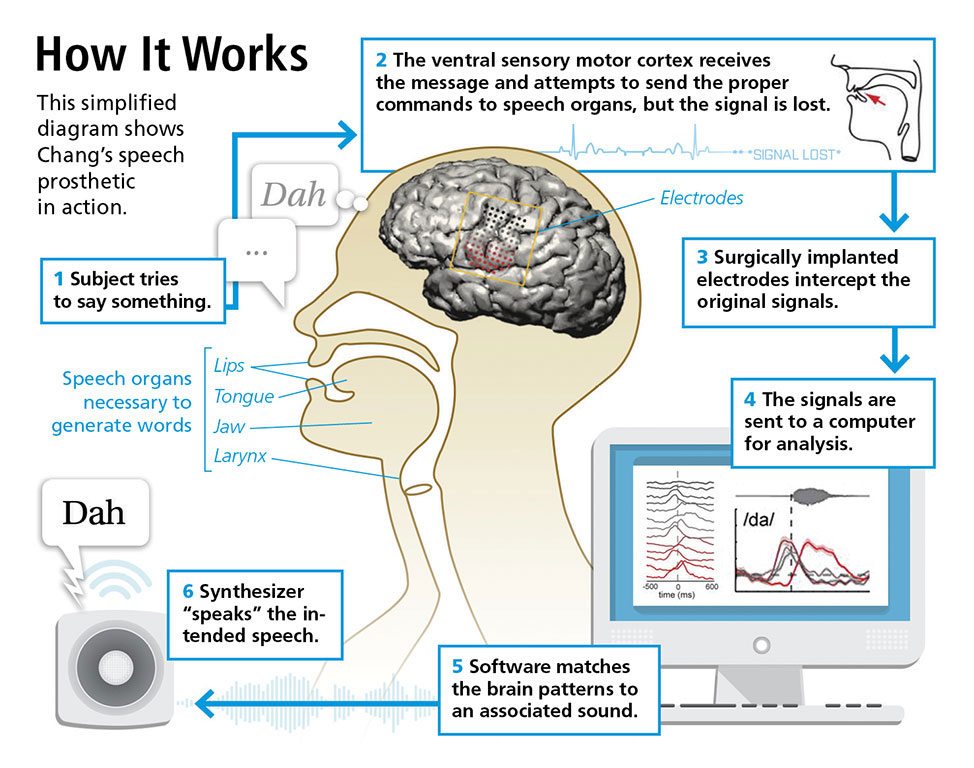

Over the past five years, Chang’s research has focused on patients with epilepsy. He has performed surgery to implant an array of electrodes beneath the patients’ skull in order to map certain types of brain activity. In the future, similar devices could be used to record electrical signals from within the motor cortex area of the brain; signals that are responsible for stimulating the movements of the jaw, lips, tongue and vocal chords that lead to vocalization. Though several areas of the brain are involved in speech, Chang believes that the motor cortex is the most important for this type of research. Once recorded, the electrical signals could be transmitted to a computer, which will translate them into audible speech via a voice synthesizer.

Chang and his team have been mapping the brain’s speech centers by monitoring electrical activity while patients made basic sounds such as “goo,” “dee” and “bah.” The data will help them to determine how the motor cortex functions and in which sequence neurons are activated during voluntary speech.

This work is very challenging and Chang still has a long way to go, but his hope is that this form of vocal prosthetic could help people whose brains are unable to directly stimulate speech production. It could give voices to people who have suffered a stroke, brain trauma, spinal cord injury or ALS. Chang expects to begin human trials on the BCI voice synthesizer within the next three years.

Image credits: Discover Magazine