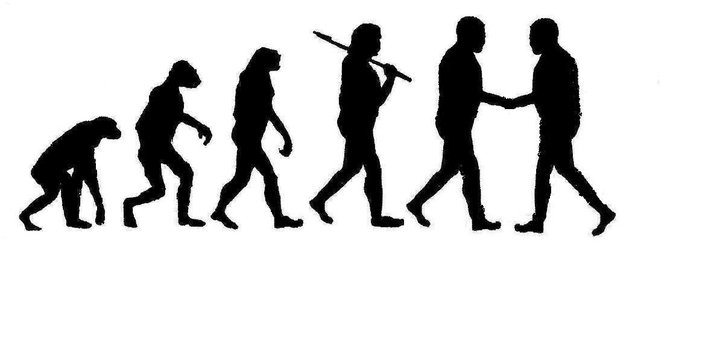

Human beings are not the biggest animal on Planet Earth. Neither are we the strongest, fastest, sturdiest, or longest living. However, we have become the most successful apex predator in existence as we know it. How have we accomplished this? What sets us apart is our intelligence and ability to use tools. These interrelated abilities have allowed us to overcome our environment and any other predators we have faced.

Furthermore, humanity has distinguished itself by radically altering the world around us to suit our needs. We have even escaped the bounds of the very planet that birthed us, soaring into space on fiery rockets in defiance of gravity. We are the unparalleled conquerors of all that we survey, the pinnacle of evolution.

And we’re just getting started.

“We are more different genetically from people living 5,000 years ago than they were different from Neanderthals,” according to John Hawks, University of Wisconsin anthropologist. “Five thousand years is such a small sliver of time – it’s 100 to 200 generations ago. That’s how long it’s been since some of these genes originated, and today they are in 30 or 40 percent of people because they’ve had such an advantage. It’s like ‘invasion of the body snatchers.’” Hawks continues, “What’s really amazing about humans, that is not true with most other species, is that for a long time we were just a little ape species in one corner of Africa, and weren’t genetically sampling anything like the potential we have now.”

What this would tend to suggest is that not only is human evolution still occurring, but it’s accelerating. To put this in perspective, since the stone age, human evolution has occurred at a rate that is roughly 100 times faster than at any other period in human history.

But this still isn’t fast enough for us.

We use technology to overcome what to us seems like the “sluggishness” of evolution. A perfect example can be found in the treatment of diseases. Normally, a disease would decimate a population, but a certain number of that population would have a gene that makes them resistant to that disease, thereby surviving and passing that gene on to their children.

However, with the introduction of antibiotics, antivirals, and other medicines, we’ve partially removed ourselves from that cycle of natural selection. Now, with the dawning age of genomic medicine and advances in the field of epigenetics, we are beginning to be able to understand and guide the very process of evolution itself. And where biology fails us, we’ve created technology to bolster us. Artificial organs are approaching near parity with natural organs, which will likely happen in the next several decades. Not to mention all the currently available technological devices we use on a normal, daily basis to overcome our “natural limitations.”

It’s extremely easy at this point to veer into the realm of speculation, imagining a future where altering our genome produces distinct species of humanity, or where cybernetics produce humans who are as much machine as man, but that’s not what this column is about.

When the implications of future technology are so startlingly vast, it’s easy to focus on that without ever stopping to ponder the implications of where we are now.

So, if you would, pause for a moment and consider: Humanity has begun to consciously guide and alter its own evolution. We have transcended the limits of our own minds by storing information on technological devices, and the limits of our own bodies through medicine.

For 200,000 years the micro-evolution of homo sapiens sapiens was accomplished through natural selection. That is no longer the case. It’s hard to pin down the exact moment it happened, though two prime candidates would be Louis Pasteur’s work with vaccination in the late 1800’s or Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928. Even in centuries we look back on as being technologically primitive, humanity had already begun to take control of their own evolution.

The weight of that statement is so profound that it’s almost impossible to comprehend. However, because the shift from natural selection to guided evolution has been so incremental to the way humanity perceives time, it’s been easy to overlook. Only now, as we stand on the precipice of fully taking control of our own evolution and with it the whole of the future, do we begin to become aware of the ethical implications.

However, even bio-ethics and the ethics of emerging technology have been largely limited to specific situations, discoveries, or technologies. As the pace of discovery continues to exponentially increase, we can no longer afford to rely on this approach. Ethics can no longer be reactive, it must become proactive.

Guiding principles must be developed in advance of technological and biological advances, not in response to them. More than any specific discovery, an overarching ethical framework, or lack thereof, will decide whether our future is utopian or dystopian.