This article was written and contributed by Thomas A. Campbell, Ph.D. and Jon Fetzer of FutureGrasp, and was edited and published by the Emerj team.

Since early 2017 when the Canadian Government published its Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, generally recognized as the world’s first artificial intelligence (AI) national plan, there has been an explosion of interest by States to release their own visions of where and how they see AI contributing to their economic growth, military postures, and cultural and societal benefits.

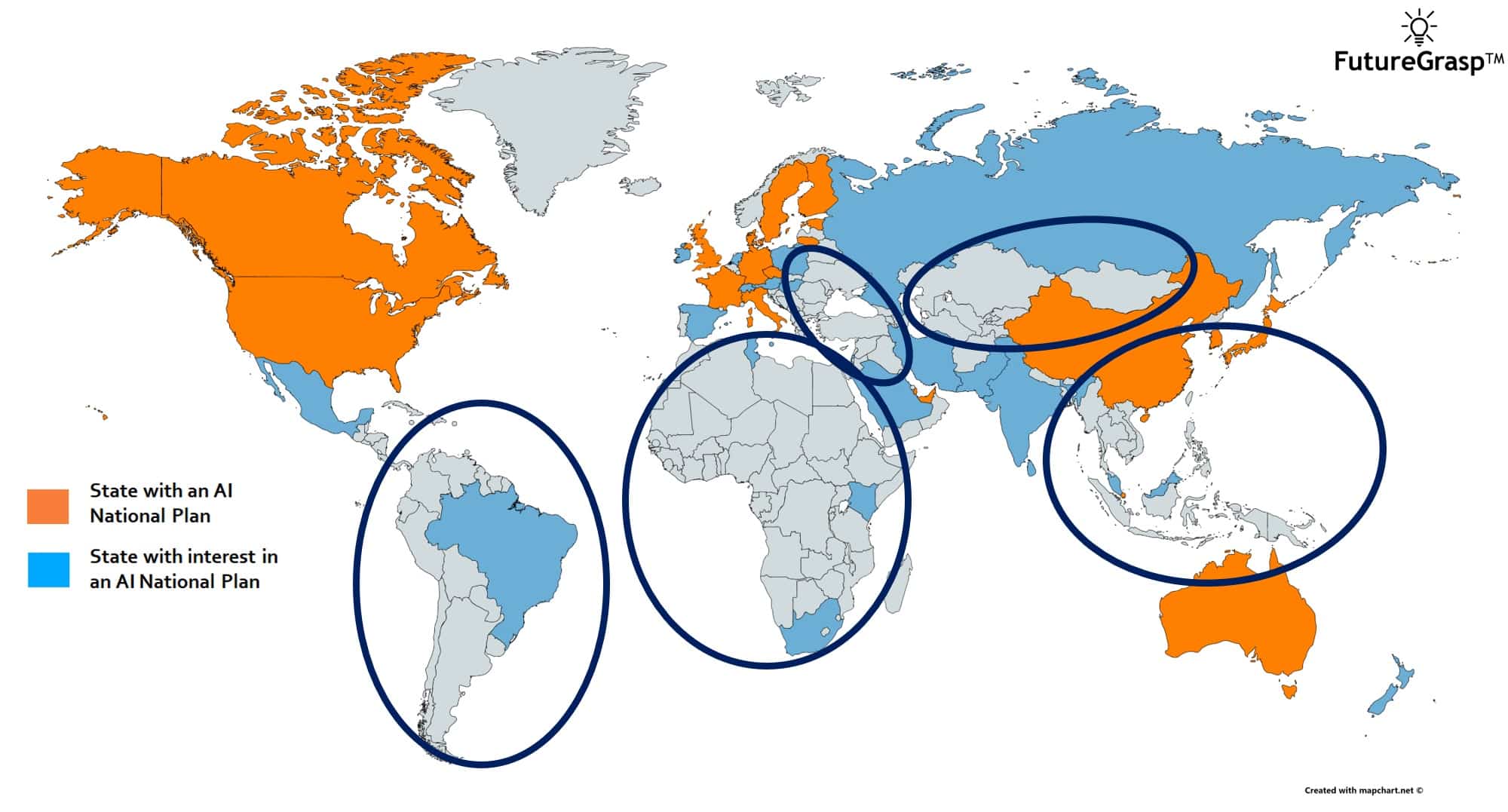

According to a recently published report by FutureGrasp, Artificial Intelligence: An Overview of State Initiatives, there have been 19 AI national plans published with 22 additional States interested in or actively developing one up to early June 2019.

While interesting from a geopolitical perspective, should AI national plans and their related government investments be on the radar of the C-suite? Why should corporate leadership care if a State decides to draft a guiding document for its nation’s AI activities?

This note breaks down why corner office leadership should be not only interested in State AI initiatives, but they should also appreciate that it is imperative to understand and engage in them.

The figures below list and show geographically the States that have an active or have expressed interest in an AI national plan up to early June 2019. The global map indicates with circles those regions with little to no AI activity from their respective governments. What is striking about this data is not so much which countries have AI activities already – generally the wealthier, more developed States – but those which have no activity at all.

Of the United Nation’s 193 member States, only 41 States are represented. Notably, it is observed that there are few States with AI national plans or significant investments in several geographic regions, including: South America, Africa, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia.

Such geographical heterogeneity presents both challenges and opportunities for the C-suite. FutureGrasp describes below five core reasons why State AI initiatives should be of strong corporate interest:

- Amplifying business

- Finding hires

- Executing R&D

- Appreciating societal sentiment

- Grasping ethics & legal liabilities

Amplifying Business

States that have active AI national plans will be more disposed to corporate engagements and investments. Amplifying industrial activity is a core part of several existing AI national plans. Per the FutureGrasp report, State funding for Industrial Strategy as an AI sector is allocated by nine States: China, Finland, Germany, The Republic of Korea, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, The United Arab Emirates, and the United States.

Investing in promising startups and medium-sized enterprises, as well as identifying companies for potential acquisition, is thus going to be naturally easier within such States than approaching States that have no specifically delineated strategy for engaging with the corporate world. For example, the Korean plan, Mid- to Long-Term Master Plan in Preparation for the Intelligent Information Society Managing the Fourth Industrial Revolution, is designed to encourage public-private-partnerships between the Korean Government and industry.

States that have not yet engaged in AI national plan developments also present unique opportunities for corporate leadership; for example, there may be AI market sectors not addressed yet within those States. Local universities can help fill gaps in research and development, even proactively working with corporations toward AI commercialization.

For the most part wealthier States are the early adopters thus far in AI. Nevertheless, there is great potential for the application of AI in developing States.

For instance, AI can contribute to the achievement of the 17 goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by world leaders in 2015, to inter alia tackle the challenges of poverty, inequality and climate change. During the opening of the 73rd General Assembly in 2018, the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General António Guterres acknowledged this, emphasizing the potential of technologies such as AI to “turbocharge” progress towards these goals.

In all States, there may be open ‘white space’ available for intellectual property (IP) filings. The World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO) recently published an extensive analysis of IP in the AI sector.

Given that AI has potential to be applied in almost every commercial market sector, it behooves companies to execute patent searches in specific States to see if a patent ‘thicket’ already exists, or if filing opportunities could be leveraged ahead of the competition.

Lastly, regulations imposed by States can affect dramatically how companies do business with them. As summarized by Emerj, there is a trend now within AI for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to advise and recommend new policies. Global companies should be aware of and possibly engage with such groups, so that they can effectively embrace the potential to help guide the drafting of AI national plans and related regulations toward their corporate interests.

Finding Hires

The challenge of finding AI experts is universal to all States. Depending upon immigration policies for an individual State, it might be best either to bring talent into the local environment or to hire coders for remote work. But finding qualified AI programmers can be a significant task.

The dearth of AI professionals is so profound that there is even a bit of a chicken and egg problem between academia and industry: top AI faculty are being hired away from universities at exorbitant salaries, thus precluding the training of new professionals needed by those very companies.

Several States have STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) initiatives to help address this problem, as detailed in the FutureGrasp report. The AI investment sector, Talent / Education, is specifically mentioned in 11 States’ AI national plans or work group reports: Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Lithuania, Sweden, The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States. Engaging with these States may offer new opportunities for finding AI talent.

Talent can also be found in States that may not necessarily be on the radar of C-suite leadership. For example, Israel has a highly robust AI startup ecosystem. Estonian entrepreneurs have raised funds which some might consider outsized for a State of only 1.3 million people.

Executing R&D

Companies that lead in AI R&D will lead in AI applications; many States recognize this and are investing accordingly. In the FutureGrasp report, it is noted how the AI sector Research is by far the most popular among States, with 16 of 19 States investing in AI identifying research as a critical focus within their AI national plans.

Denmark, India, Japan, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States all have specific line items in their national budgets for AI research. Knowledge of and engagement with such States are critical to C-suite leadership, as they can then decide which States lead innovation and which States’ startups might be leveraged or acquired.

Appreciating Societal Sentiment

In the history of disruptive technologies, there are numerous examples of technology adoption pushback from grassroots movements, sometimes yielding societal avoidance of products or even a State policy banning specific technology uses.

For example, in the early days of nanotechnology there were calls for a moratorium on the use of nanomaterials (generally defined as any material with a base measurement of between 1 and 100 nanometers).

Claiming the need for further research of health and environmental implications of nanomaterials, public groups heavily petitioned governments to forego nanotech funding and industry to wait on sales of such materials. Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are also a classic example of good science viewed badly in the eyes of the public. State policies are imposed upon much of the European Union not to use GMOs within food products.

Similar movements and bans have potential to arise with AI. For example, San Francisco just recently banned the use of facial recognition via AI within its city borders. It is thus critical for the C-suite not to ignore public sentiment surrounding AI. As a platform technology that encapsulates and enables dozens of other market sectors, AI offers great potential.

Nevertheless, some in the public may consider it a mysterious feature – one cannot touch, taste or see an AI algorithm. States that have programs active in ethics and other spaces should be engaged by C-suite leadership to help temper such fears.

Otherwise, even with the best algorithms, companies may find themselves blocked from deploying AI within a country because of a lack of public understanding or misplaced sentiments.

Grasping Ethics and Legal Liabilities

Ethics issues and potential legal liabilities present on-going challenges for the C-suite in all technologies, but perhaps even more so in AI. AI could be considered a platform technology – i.e., AI spans numerous market sectors, provides a range of problem solutions, and presents flexibility and adaptability in our changing world.

Thus, C-suite must be aware not only of potential intended positive uses of internally developed and/or State-sponsored AI capabilities, but also their potential misuses.

By co-developing AI with States, corporations may unwittingly assist governments in their creation of security threats to the United States and/or to the international community writ large. For example, surveillance technologies can compromise the privacy of citizens, or in worst cases result in incarceration or deaths of innocent people.

Thus, it is imperative that C-suite leadership is aware of potential abuses of their AI work by foreign States. Companies may have to make judgment calls on AI projects for their ethical and legal implications, looking beyond mere profits to avoid potential litigious situations.

Summary

Ultimately, the C-suite should not only have an eye on State initiatives, but also be engaged with States active in AI as their policies will affect corporate bottom lines.

Amplifying business, finding hires, and executing R&D can thus be aided by political engagement by companies. Maintaining a knowledge of, and possibly influencing, public sentiment and keeping a firm grasp of ethical and respective legal liabilities are oft-overlooked cornerstones for successful technology adoption.

Navigating the complexities of State initiatives requires global perspective and experience. FutureGrasp and Emerj offer these panoptic views to assist C-suite leadership in capitalizing with States interested in developing their AI ecosystems.

Header Image Credit: Cain Live