(Alternative Montaigne-like title for this essay: “That the Meek Must Feign Virtue”)

When I first became focused on the military and existential concerns of AI in 2012, there was only a small handful of publications and organizations focused on the ethical concerns of AI. MIRI, the Future of Humanity Institute, the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, and the personal blogs of Ben Goertzel and Nick Bostrom was most of my reading at the time.

These limited sources focused mostly on the consequences of artificial general intelligence (i.e. post-human intelligence), and not on day-to-day concerns about privacy, algorithmic transparency, and governing big tech firms.

By 2014, artificial intelligence made its way firmly onto the radar of almost everyone in the tech world. New startups began (by 2015) ubiquitously including “machine learning” in their pitch decks, and 3-4-year-old startups were re-branding themselves around the value proposition of “AI.”

Not until later 2016 did the AI ethics wave make it into the mainstream beyond the level of Elon Musk’s tweets.

By 2017, some business conferences began having breakout sessions around AI ethics – mostly the practical day-to-day concerns (privacy, security, transparency). In 2017 and 2018, entire conferences and initiatives sprung up around the moral implications of AI, including the ITU’s “AI for Good” event, among others. The AAAI’s “AI, Ethics, and Society” event started in 2016, but picked up significant steam in the following years.

So why the swell in popularity of AI ethics and AI governance?

Why didn’t this happen back in 2012?

The most obvious answer is that the technology didn’t show obvious promise for disrupting business and life back in 2012. People in Silicon Valley, never mind elsewhere, didn’t have AI squarely on their radar – and today – AI and machine learning are recognized squarely as disruptive forces that will likely change the human experience, and certainly the nature of human work.

Now that AI is recognized as a massively disruptive force, people are interested in ensuring that its impacts on society and individuals is good. Certainly, much of the origin of “AI Good” initiatives stems from a desire to do good.

It would be childishly naive to believe that AI ethics isn’t also about power. Individuals, organizations, and nations are now realizing just how serious their disadvantage will be without AI innovation. For these groups, securing one’s interests in the future – securing power – implies a path other than innovation, and regulation is the next best thing.

In this essay I’ll explore the landscape of AI power, and the clashing incentives of AI innovators and AI ethics organizations.

AI Innovation Grants Power to (Some) Countries and Companies

The most fundamental principle of power and artificial intelligence is data dominance: Whoever controls the most valuable data within a space or sector will be able to make a better product or solve a better problem. Whoever solves the problem best will win business and win revenue, and whoever wins customers wins more data.

That cycle continues and you have the tech giants of today (a topic for a later AI Power essay).

No companies are likely to get more general search queries than Google, and so people will not likely use any search engine other than Google – and so Google gets more searches (data) to train with, and gets an even better search product. Eventually: Search monopoly.

No companies are likely to generate more general eCommerce purchases than Amazon, and so people will not likely use any online store other than Amazon – and so Amazon gets more purchases and customers (data) to train with, and gets an even better eCommerce product. Eventually: eCommerce monopoly.

There are 3-4 other well-known examples (Facebook, to some extent Netflix, Uber, etc), but I’ll leave it at two. AI may change to become less reliant on data collection, and data dominance may eventually be eclipsed by some other power dynamic, but today it’s the way the game is won.

I’m not aiming to oversimplify the business models of these complex companies, nor and I disparaging these companies as being “bad”. Companies like Google are no more filled with “bad” people than churches, law firms, or AI ethics committees.

The promises of AI’s rolling snowball of data dominance – and the evident advantage of the companies doing so already – leads to the conclusion that there might only be a few companies and countries will hold an AI advantage in the coming decades.

There are only a very small number of organizations with sufficient talent, resources, data science infrastructure, and reach capable of bringing world-changing AI innovation to life today. Among them:

- Google / DeepMind

- Amazon

- IBM (…maybe?)

- (Various departments within the US government and military)

- (Various departments within the Chinese government and military)

- Baidu

- Tencent

- Potentially:

- ByteDance

- Alibaba

- (a handful of others)

(Those above-mentioned entities are also the most likely to potentially construct artificial superintelligence – but that will have to be the topic of another article.)

When it comes to near-total hegemonic power over the globe, there are, at present, only two viable competitors:

- The United States

- China

The longer the time horizon, the more the odds tip in China’s favor.

So if you’re an ambitious or self-interested person, and you don’t own a massive share in one of the genuine “AI powerhouse” companies, and you aren’t in the leadership of one of the government of the USA or China… how are you supposed to keep up in the game of power?

AI may grant nations unprecedented economic and military might. While this could lead to aggregately more abundance for all of humanity, the spreading of that wealth would – to some degree – be in the hands of the relatively few companies or nations who acquire that AI advantage.

How can such a person ensure their significance and ensure that they aren’t left behind as the “AI powerhouses” gobble up all the influence and power?

How can people outside of the AI innovator circle ensure their interests are represented in an increasingly AI-dominated future?

Other paths are available to them:

Regulation and Innovation are Both Paths to AI Power

How can ambitious people outside of the AI innovator circle gain power and prominence if they can’t possibly compete with the US, China, Google, or Baidu?

One path would be to regulate or govern this new power, evoking the banner of “the people.” This could be done through a variety of means:

- Limiting and diminishing the perceived imbalances, slowing or hobbling the powerful

- Breaking up or tearing down entities that are perceived to be too powerful

- Forming and/or running governing bodies that are more powerful than the powerful entities in question

These aims could be pursued in order to benefit wider society, or they might be done simply to level the powerful and establish a position of prominence and control in their own hands. I have met leaders in various “AI ethics” movements who seem motivated by their potential good, and others who – behind closed doors – are unabashedly clear about AI regulation as a path to power and prominence.

The banner of “goodness” or of “the people” is most likely to be carried by nations and companies and organizations that have little hope of ever competing directly for power on a global scale.

The leader of France or Sweden or Canada cannot reasonably expect to quietly amass power in the form of economic and military advantage – they understand frankly that Silicon Valley, Beijing, and Washington D.C. will be the locus of much of that power.

No matter how many government initiatives or entrepreneurship programs Sweden creates, it is unlikely to become globally dominant in the military or economic sphere.

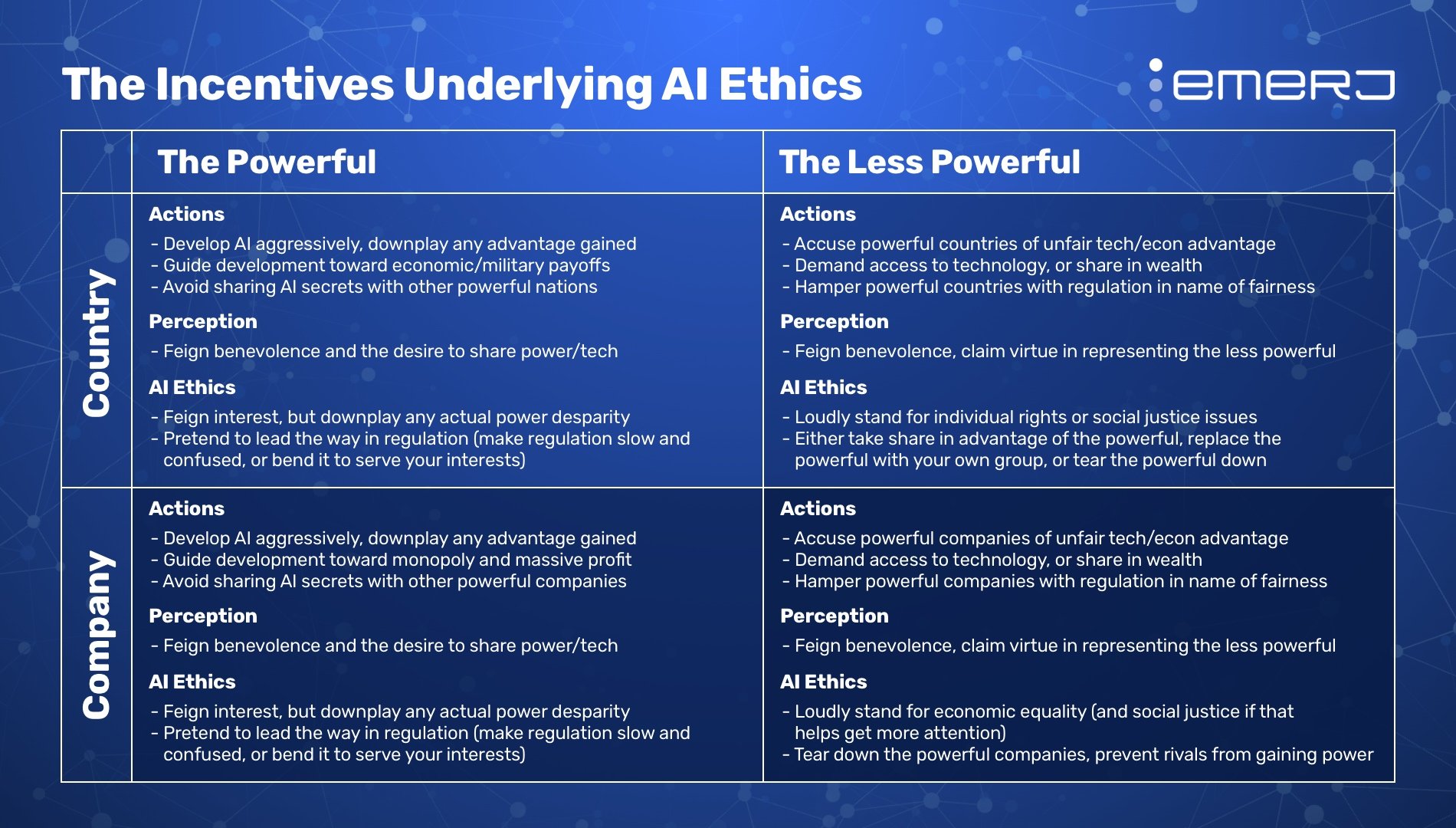

The incentives of the powerful have always been different than those of the less powerful, and the means of gaining prominence for the two respective groups are also different. This is what it looks like in the realms of AI innovation and AI ethics:

The advantage of the less powerful regulators in the AI power race is that they their interests are aligned with the interest of most people, most organizations, and most countries. This is because most companies and countries are less powerful.

This has nothing to do with who is more self-interested or more altruistic. Napoleon and Robespierre were once the underdogs fighting under the banner of “the people”, but were happy to drop this pretense when they reached the top (and indeed, pick it up whenever propaganda made it convenient). Most of the less powerful never reach a position of power, and so are able to maintain the pretenses of being “good.”

Those at Google are just as selfish and amoral as those at OpenAI. Those within the US Department of Defense are just as selfish and amoral as any “AI ethics” group. The difference is that the argument of the less powerful groups will almost always ring sweeter for “the people” (the less powerful majority of people, companies, nations) themselves.

The argument “Those bad people have too much power and they’re keeping good things from you” has, for the last few hundred years (at least in the West), been stronger than “We few have the power and we’re welding it for the best interest of ye, the masses.”

Some of the weaker parties understand that the banner of “the people” is all part of the power game. Most of them, though, conveniently suspect that the intentions of the powerful (those who don’t share their interests) are “bad”, and suspect that the intentions of the weaker parties (those who mostly share their interests) are “good.”

And so revolutions occur, and regimes change, and those on the top are toppled.

The Power Grab of Artificial Intelligence Governance

These same dynamics of the banner of “the people” will continue to play out in artificial intelligence.

The people in the US Department of Defense, Facebook or Google are not railing against the risks of AI, and the risks of concentrated power.

Again, whenever possible, it generally behooves the powerful to quietly amass their resources and advantage without drawing notice or resentment of their power.

Those who are losing the AI race (the race for truly super powerful AI, potentially artificial general intelligence) will rail against concentrated AI power. Not out of selflessness, but out of the same self-interest that makes the powerful organizations stay quiet.

At the World Government Summit this year, I was at a roundtable with a representative from OpenAI. I asked frankly:

“Would Elon Musk have created OpenAI to ‘democratize’ AI if he was at the helm of Google instead of Tesla and SpaceX?”

“Well, probably not” was the response. It’s not a bad response, it’s not an admission of some immorality, it’s merely an admission of AI ethics being a path to power for those who can’t innovate their way there.

Since that event (February 2019), Musk is no longer associated with OpenAI, and OpenAI has turned itself into a for-profit entity so that it can compete on AI innovation, not regulation.

This example is important because it illustrates a point I’ve parroted a thousand times:

Companies will strive for power through AI innovation (the most direct path) whenever they can, and they will compete via AI regulation only when they must.

Europe as a whole must compete on regulation, as they have no other choice.

Two years ago OpenAI must have competed in much more modest ways, by sharing their research and aiming to proliferate AI knowledge. With enough money and talent, however, they will. The strong are the most likely to be safe, after all.

My prediction:

- “Underdog” companies under the banner of “for the people” will pivot their approach from AI regulation to AI innovation as soon as they are able to do so, just as OpenAI has. Others will follow suit, mostly in US and China.

- AI innovators who fall behind the times and lose talent or funding (might happen to IBM soon, but may even happen to Google within a decade, who knows) will pivot from AI innovation to AI regulation, as the latter will be their only option for power. This will be framed as an act of virtue, but it is an act of unadulterated self-interest.

Again, I am not morally judging these actions, I’m stating the incentives at play. All organizations, my own included, are run by self-interested humans.

This uptick in “concern” about AI from the AI regulator crowd is not because these policy experts have long been musing over the social implications of AI.

Indeed, a huge swath of the “AI ethics” and “AI policy” crowd has existed only as long as the topic has been popular (2016-2018). It is not long musing and an ardent and explicit focus on AI over the years, it is instead a firm understanding that AI will enable new vistas of power, influence, benefit, and potentially damage – and it now makes sense to leap into the conversation for benefit.

The majority of this crowd was nowhere to be seen when Bostrom or Goertzel or Hugo de Garis were hashing out these issues a decade ago or more.

Back then, the social impact and (importantly) power-enabling capabilities of the technology wasn’t self-evident. Now it is, now the interests of these regulators are at risk, and they can play the role of the virtuous meek – which is more believable (but not more true) than Google and Baidu playing the role of the virtuous strong.

So, by carrying the banner of virtue, ethics and governance, groups can speak openly about its ethical concerns, they can take big tech down a peg, and they can form organizations that can do the next best thing to building super-powerful AI:

They can create and be part of groups that manage or govern these super-powerful AI.

This is because many of them understand that whoever creates artificial superintelligence may be able to control it, direct it, and have their interests represented in the AI-enabled future, much more than those without it. Some AI regulation groups are only focused on present concerns, but many have an eye on the control of this technology when it is mega-powerful, as opposed to its moderate capabilities today.

In a more ultimate sense, whoever controls artificial superintelligence will potentially wield the power to quiet literally control the world, and determine the trajectory of intelligence itself. This article is about more near-term AI implications, so I’ll have to save the AGI power game for later essays (interested readers may want to skim my Final Kingdom essay on danfaggella.com).

Dealing with the Self-Interest That Drives Regulation and Innovation

By absolutely no means am I painting AI ethics and AI governance efforts as inherently malicious.

AI ethics groups are not full of bad people – they are merely full of people, humans. And of humans in a weaker (i.e. not technologically powerful) position, it might be said:

Of those who rail against tyranny are many who long to be tyrants.

Powerful or weak, humans who will naturally do whatever behooves their ends (as all humans do).

Economic power and political interest are not always vicious things to seek, nor are they virtuous. They are almost always advantageous, however, and so the technical innovators will pursue them with monopoly force and spending billions on lobbying – and the governance groups will pursue them through regulation and control of a different kind.

We should sympathize and have compassion for the selfish condition of man (neuroscientist and policy thinker Nayef Al-Rodhan’s term is “emotional amoral egoism”, which is remarkably apt).

Broad individual rights/social justice concerns (some valid, some silly) will get magnified attention under the obscure header of “#AI Ethics” for a little while.

Ultimately, AI ethics is abt using Robespierre model to power, not Bonaparte model. All is self-interest. pic.twitter.com/BpDytDOTwx

— Daniel Faggella (@danfaggella) April 23, 2019

While we should aim to be good and hope that others will be, too, we should operate under the belief that humans will do what behooves their own interests. Rather than chastise or accuse humans or groups, we should build governance mechanisms that take this inherently amoral egoism into account.

If the AI ethics conversation continues – as it seems to have begun today – as the “good” non-profit people and the “good” policy thinkers versus the “bad” innovators and businesses, we will have made false saints who will inevitably let us down.

We will put more faith than we should on those who often sit on the outside of the harsh world of commerce and competition (the world of people who manage private enterprises).

There seem to be a few tenets by which we can manage the self-interest of the parties involves in AI’s future:

- We should not allow the AI ethics conversation to slide into black or white, “bad” or “good.” Rather, we should see multiple perspectives as important, but we should understand that all groups and individuals will do what behooves them.

- We should aim for governance structures that can cope with the rampant self-interest of all individuals and groups involved.

You ask: “Does Daniel want a world ruled by Google or Baidu or some AI monopoly?”

Nay. I want a balance of power. The AI ethics conversation is an aggregate good and should be fostered – but regulators should be seen to be as selfish and amoral as innovators.

Today most all AI ethics groups get along well despite an unspoken assumption that they are all vying for limited influence, recognition, and power.

The danger is not that a particular class is unfit to govern. Every class is unfit to govern. – Lord Acton

Divisions between their followers and squabbles between their organizations will, in the next few years, be inevitable – probably just as tribal as the “AI ethics versus tech companies” dynamic today.

The next 2-3 years will see AI ethics orgs fighting mercilessly amongst themselves, just as companies do in the private sector. AI ethics groups hand more-or-less banded together now because it behooves their interest, but this will not be the case as real political influence becomes accessible to them.

On the Benefit of More Voices in the AI Power Conversation

On the aggregate, I see the flourishing AI ethics and governance conversation as good for humanity, and for the probable technological transitions we have ahead of us. The sense of concern for those left behind in the technological wake is in many cases genuine, and heartening.

It can be said that the less power can use the opportune banner of “the people” whenever they put up resistance to – or aim to usurp – the powerful.

This is opportune, in that the people easily attribute virtue to a leader that they believe behooves their own interests.

Fere libenter homines id quod volunt credunt. – Caesar

But it is also often true. Less powerful groups do often represent the interests of the “many” versus the powerful “few.” Even if motivated by raw selfishness, less powerful groups having a say against more powerful entities often represent the interests of other less powerful groups like them.

For example:

- Small countries who are unable to develop autonomous weapons may evoke human rights as a reason to cease development or use of autonomous military robots

- Smaller businesses who are unable to dominate data may change the anti-trust laws (in the US and elsewhere) to break up unassailable technology giants

- Concerned political parties may enact significant regulation about how their personal data is used by companies and governments online, pushing back against surveillance or hyper-personalized marketing

In all of the above cases, the interests of the greatest proportion of humanity is probably represented by the weaker party making its case against a stronger party. This isn’t always the case, but it is almost always the case that the weaker party can better evoke the banner of “the people.”

Of course, sometimes these underdog groups come to power themselves (Robespierre), and their attitudes, naturally, change to a position of consolidation, not of revolution. In their initial and weak phase, however, they probably accurately represented the interests of the masses of which they were originally a part.

Even if AI ethics was little more than virtue signaling (today it’s much more than that), it would probably be an aggregate good.

For example “Corporate Social Responsibility” (CSR) initiatives and “Sustainability” practices started off small. Many businesses 30 years ago may have believed that support of their community – outside of treating employees well, making payroll, and acting within the law – was not their duty.

However as organizations took stances on social issues, volunteered time, and differentiated themselves through programs for “giving back” and “protecting the environment”, the idea because more accepted.

Even if the first generation to enact CSR feel that it was little more than putting off bad press by appearing virtuous – or at least not malicious (as we might suspect most “AI ethics” initiatives within large organizations are today) – the next generation saw CSR as part of business itself, and maybe even as an opening for new business opportunities beyond moral “brownie points” (the equivalent of “greenwashing,” or pretending to be sustainable without actually changing any business practices).

Already we’re seeing startups considering the business upside of transparent AI systems that better meet the expectations of technology users. Even if these efforts are unadulterated self-interest (which is a harsh presumption, many such companies are probably founded with a genuine need to make a positive difference), this moves the needle on technology norms to directly include (at least ostensibly) the considerations for the user’s privacy and wellbeing.

Voices in this camp of individual rights and considerations for wellbeing are probably a necessary and beneficial counter-balance to the increasing power of the companies who dominate the virtual world (tech giants like Google, Facebook, Amazon, etc).

Whether this positions the individual rights-focused, ethics-happy Western world to win the arms race of AI development with China… that’s another story altogether, and that’ll have to be another article.

More voices will hopefully mean more opportunity for good ideas to arise, for the public to be involved, and for proper balances between governments, innovation, and individuals. This is the hope, and I think it’s a reasonable hope to hold onto. I could never have imagined in 2012 just how much traction AI ethics would have today – and I hope more people from business, government, and international relations join the conversation about how AI should be governed for a (hopefully) more fair, just, and prosperous world.

Concluding Thoughts and Attempts at Optimism

The American industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt had a great many enemies in business (Daniel Drew and Cornelius Garrison among others). He fought fiercely against these men in business and in court during the rough-and-tumble early days of American commerce.

In reading Vanderbilt’s biography, I was surprised to learn that in his later years he was apparently friends (not just friendly) with many of these former enemies, and would enjoy drinks, cigars, and laughs with them.

Maybe this was an astute example of keeping one’s friends close and one’s enemies closer. He was a shrewd and aggressive businessman if there ever was one – and his friendships might have been little more than politics.

Maybe, however, it was a frank understanding of humanity, human motives, and the nature of power.

He seems to have understood that people will always fight over limited resources, and they will call their cause “good” and another’s “bad” in order to gain legitimacy or political backing – but that behind it all is a camaraderie of being in the same game. Vanderbilt seems to have been able to make merry in private life with those he was forced to tout as “enemy” so many times in public life and in courts of law.

I’m not calling Vanderbilt moral role model – I’m merely using anecdotes about the man’s later life.

Even in the great fray of this state of nature of ours, there are pockets of understanding that we’re in this selfish and cruel world together – and that we should be able to laugh about it, and respect one another – even if we can’t do so in the courtroom where we must feign moral opposition to one another.

If we can squarely understand our respectively selfish amoral nature, we can empathize. We can be ready for struggle. If we know that competition is natural, and cooperation only occurs when it behooves both parties, we can blame others less, and aim to foster situations where cooperation would benefit as many parties as possible.

There is a virtue, I think, in understanding what we would do in the shoes of the other.

AI ethics organization leaders are likely to speak at length about the virtuous and benevolent things that they would do if they were Larry Page or Mark Zuckerberg. The odds are, they would do precisely what the people at the helms of those companies would do. Conveniently they hold no such power, and so can argue from a position of pristine and powerless virtue.

On the other side of the coin, every private sector highly influential AI tech executive would do exactly what the AI ethics groups – or the smaller industry businesses – are doing if they were in their shoes. Aware as they are of the economic and political power that these technologies wield, tech leaders left without that power would almost certainly want to grasp it – or distribute it – through political means.

As humans we play a deceptive game of virtue. We pretend that we would not do exactly as our adversaries do if we were in their shoes. What is against our interests is “bad”, something totally beyond saints like us.

This is natural for politics, natural for influence, natural for swaying the masses. I think it the height of pettiness and disingenuousness, and I believe it does nothing for the cause of peace – a peace the must address squarely our deceptive and selfish natures.

America didn’t want to lean on Rockefeller the arbiter of the US economy, and indeed it broke up Standard Oil.

Similarly, France should not have leaned on the “virtuous” underdog of Robespierre.

As I’ve said before, the massive rise in AI ethics is probably a boon to humanity. But there are no saints, no “purely well-intended” who stand against the “purely ill-intended.”

I have met and spoke with many of the people at the helm of AI ethics initiatives.

Some are of the same brashly ambitious and cunning fiber that many think exist only in the world of business or politics (in case I haven’t made it clear, AI ethics and governance is politics).

Many are plainly in the ethics crowd because it is a mindless extension of their political beliefs and a signal of virtue, of ostensibly being a protector of the oppressed.

Plenty of them are genuinely empathetic people, carrying an extension of well-intended and deep personal values forward into the future developments of technology.

Most are probably a little of all three.

So are most business leaders, and most politicians.

So am I.

So are you.

…

See you next week on AI Power.