The vision of an army of small unmanned aerial vehicles streaming through the sky to rapidly deliver food packages has captured the imagination of the public, the media, and most importantly some of the largest companies in the world. Achieving this vision won’t just require overcoming the technological and safety challenges, but also significant buy-in from the public and policy makers.

There are many current commercial uses of small unmanned aerial systems (referred to as UASs, UAVs, or drones) such as a farmer using one to survey their fields which are legally simple. Delivery drones, public mapping drones, or any UAS meant to travel outside a single property creates a whole different legal situation.

It is very difficult to picture how a system of delivery UASs could be widely used and commercially viable unless these vehicles have the right to travel over public roads and/or private property not owned by the delivery companies. Allowing that is going to require legislative and regulatory changes.

This article examines the legal and political challenges delivery drones face and will need to overcome before they see widespread use:

- The current state of drone regulation in the USA, UK, and Australia (similarities and differences)

- How quickly the rules are likely to change in these countries

- An overview of political challenges which may slow down regulation changes in the near term

For business leaders: By the end of this article, you’ll have a solid grasp of the state of drone regulation – and you’ll be able to take the present trends into account for strategic planning and competitive intelligence.

In most countries there is a long established legal tradition, dating back to the birth of commercial air flight, which dictates that the space directly above a piece of property belongs to the property owner, while the higher-altitude airspace used for commercial travel belongs to the government. This legal divide was fairly simple when it only involved large manned aircraft that needed to travel hundreds or thousands of feet in the air for safety reasons, but commercial UAVs are changing the dynamic.

Delivery drones will likely operate between just a few feet to a few hundred feet off the ground, and new rules will be needed to address this. We’ll begin by examining the present state of drone flying regulations.

(For readers with an interest in other drone applications, see our previous articles on delivery drones and industrial drone applications.)

Where the Rules Currently Stand

The main focus will be on the United States, since it is home to several of the most prominent technology companies developing delivery drones and would potentially be one of the largest markets for delivery drones.

This article will, however, address other countries. The slower pace of regulatory change in the United States has in part caused Amazon to test delivery drones in the UK and Alphabet to test them in Australia. Currently these countries offer easier places to test and perfect the technology thanks regulatory waivers. Once a system is proven to work and is accepted in one jurisdiction, it often becomes easier to lobby other jurisdictions to follow suit.

United States

USA Drone Regulations in Brief:

- Visual line-of-sight (VLOS) only

- One pilot per drone

- Daylight-only operations

- Maximum altitude of 400 feet above ground level (AGL)

- Only over a sparsely populated area

In August 2016, the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) comprehensive regulations for routine non-recreational use of small unmanned aircraft systems went into effect.

The rules allow for the use of commercial drones up to 55 pounds. They can travel up to 100 mph and up to 400 feet above the ground. They can only fly during the day and are allowed to carry a payload.

The most significant restriction is that a drone must be within the pilot’s visual line-of-sight (VLOS). According to the FAA, “the small unmanned aircraft must remain close enough to the remote pilot in command and the person manipulating the flight controls of the small UAS for those people to be capable of seeing the aircraft with vision unaided by any device other than corrective lenses.”

The rules also dictate that a pilot cannot operate more than one drone at a time and that the drones cannot fly over populated areas, which basically eliminates all economic advantage gained by using AI to make drones autonomous. While waivers can be obtained for these rules from the FAA, and many have been granted, the waiver process can be slow and unpredictable.

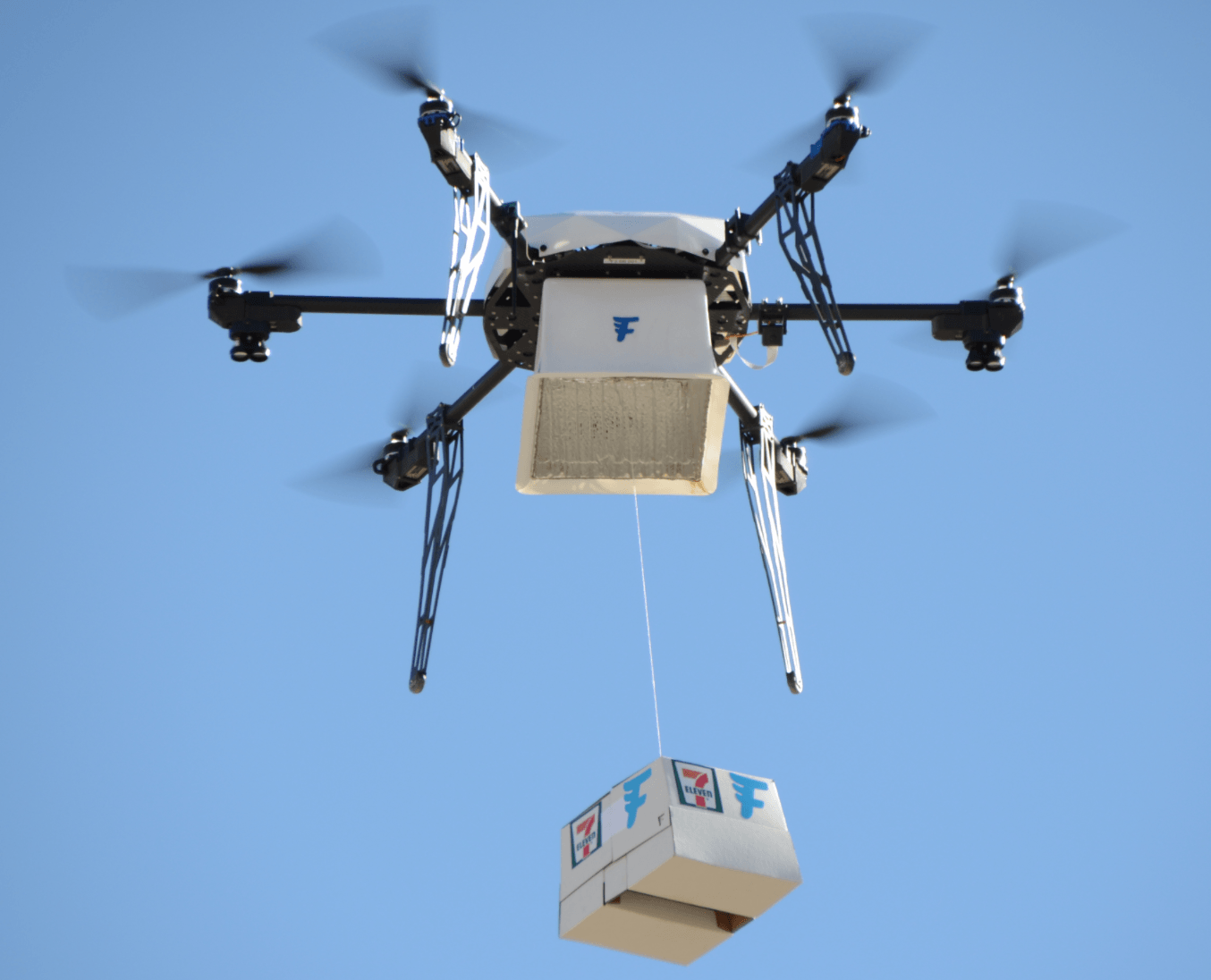

The VLOS regulation is one of the biggest barrier to many commercial drone business plans. It is technically possible to make drone deliveries with the VLOS restriction in place, as the drone startup Flirtey demonstrated with 7-Eleven in Nevada, but it would be extremely difficult to make it an economically viable system. In this demonstration all delivery were all made within one mile of the test store. While the drones flew autonomously a trained Flirtey pilots kept them in line of sight at all time ready to take over control. Replicated this for a true city wide delivery system would require hundreds of pilots on rooftops all over the city.

During this test the pilots kept the drone in the line of sight at all time.

When the FAA rules were first proposed, Amazon’s vice president for global public policy made it clear that the rules “wouldn’t allow Prime Air to operate in the United States.” After they were finalized, the Consumer Technology Association said the FAA would need to eventually address beyond-line-of-sight issues and that this change would be a “true game changer.”

United Kingdom

UK Drone Regulations in Brief:

- Must maintain direct unaided visual contact

- One pilot per drone

- Maximum altitude of 400 feet above ground

- Not with 150 metres of any congested area

On paper the regulations for commercial drones in the United Kingdom are very similar to those in the United States, but the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has been much more aggressive in providing special permissions and waivers.

In 2016, the CAA gave Amazon several important special exemptions so it could begin drone delivery tests in specified areas. These included allowing beyond line-of-sight operations in rural and suburban areas, allowing the drones to test avoidance systems, and letting one operator control multiple highly-automated drones at a time.

Allowing drones to operate this way is seen as critical to making Amazon Prime Air work as envisioned by the company. These special permissions enabled Amazon to begin its first limited private trial of its drone delivery system in Cambridgeshire.

Australia

Australia Drone Regulations in Brief:

- You must only fly by visual line of sight (VLOS)

- You must only fly one RPA at a time.

- You must fly no higher than 120 metres (400 feet) above ground level.

- You must not fly over populous areas

Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) last year also drafted rules very similar to the FAA for commercial drones when it comes to requiring a single drone per pilot, avoiding populated areas, and visual line of sight. But CASA has a clear process to get area approval for beyond visual line of sight drone use, and CASA claims to be eager to see autonomous aircrafts developed in the country.

Peter Gibson CASA Corporate Communications Manager told Emerj, “Australia’s advantage is that we had a set of safety regulations in place since 2002 that could be used effectively to cover drones as the technology emerged. While the rules were not originally written with drones as we know them today in mind, they were flexible enough to cover the emerging technology.”

Despite being based in California, Alphabet’s Project Wing is testing their drone delivery system in the Canberra region of Australia. The decision to do this was made in part because they have a good relationship with CASA, which approved their trial.

At the moment, basic commercial drone regulations are remarkably similar across several industrialized countries. The big difference is mainly how quick and aggressive the different aviation agencies are when it comes to granting exemptions or waivers for rules. This in large part explains where we are seeing different companies test delivery drones.

Drone Rules and Regulations in the Future

To move from testing to widespread use of autonomous delivery drones requires more than just targeted regulatory exemptions. A few drones being flown by one company in one specific neighborhood is relatively simple. Thousands of drones flown by a dozen different companies all potentially moving in the same airspace above a city is whole other level. That requires an entire regulatory framework covering universal safety rules, UAV air traffic control, and drone to drone communication standards.

Before autonomous drones can theoretically fly in all urban environments, there needs to be a standardized unmanned aircraft systems air traffic management (UTM) system. That is a project drone makers, NASA and the FAA are currently collaborating on.

The original timeline set out by NASA calls for demonstrating a UTM system that is capable of UAS tracking to ensure collective safety over moderately populated areas by early 2018. Next, by 2019, it calls for demonstrating a UTM system that can handle autonomous vehicles used for news gathering and package deliveries over higher-density urban areas. So far, NASA says their tests have been mostly a success, and they have been moving along only slightly behind the original schedule.

Below is a video from NASA’s recent test of a UTM system, with multiple types of drones flying simultaneously:

Once this UTM research is completed by NASA in 2019, it will be turned over to the FAA for further testing and potential rulemaking. That makes 2019 likely the earliest possible date for the FAA to create regulations that would allow widespread drone delivery but the process could take longer. Sometime in 2020 is likely a more reasonable date to expect new FAA rules, but it is also possible it could take years based on technological or political concerns.

Over the past several years the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration went through a similar process for testing vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communications standards and will soon be require the system in new vehicles.

Other nations’ aviation agencies might move faster than the relatively conservative FAA, but they are still unlikely to make big changes before 2019. Given the importance of unified standards for safety, it is likely most will rely heavily on NASA UTM research.

Political Considerations

So far, the regulatory focus has primarily been on technology and safety. Commercial drones in urban areas are still a relative novelty, but it is possible delivery drones could create a political blowback that would slow down or prevent the implementation of rules allowing them.

Privacy

There are a range of privacy concerns that could come from the growth of UAS. Any UAS traveling just above private property or along city streets will have a view into backyards and upstairs windows, which could make people uncomfortable.

Theoretically, the information gathered by UAS could be abused in numerous ways by governments or individuals. An employee that had access to all the information gathered by a fleet of UAS could try to blackmail on individual with incrimination photos or a domestic abuser could use to stalk on an individual.

Employment

There is the issue of possible job losses, which creates political concerns. According to the Bureau of Labor, over 850,000 people are employed as light truck or delivery service drivers, over 300,000 are employed as postal service mail carriers, and over 400,000 are employed as drivers/sales workers which perform tasks like restaurant deliveries.

Many of these jobs could potentially be replaced by drone delivery systems. This could possible create backlash from unions representing some of these groups.

Noise

Finailly, there is the issue of noise and aesthetics. NASA researchers found that regular people consider the noise from current UASs particularly annoying compared to traffic noise. It is possible people are simply not used to the noise, or there might be something about the noise itself that is inherently more bothersome.

As a society we are willing to put up with a range of noisy or ugly technologies from garbage trucks to telephone lines because the convenience is seen as outweighing any drawbacks. The potential for much faster delivery and much cheaper delivery could cause the public to accept any drawbacks. The companies investing heavily in delivery drones are effectively assuming as a society we will make the same trade off with this new technology, but it is not guaranteed.

A 2015 survey in Australia of online shoppers found only 11 percent want drones delivering goods they order online. A more recent survey for the USPS found 44 percent like the idea of delivery drones while 34 percent dislike the idea, but many had reservations. There was a massive generational gap with young Americans much more supportive than older Americans. Older Americans are more likely to vote and get politically engaged, especially in local politics.

Concluding Considerations for Business Leaders

The technology behind commercial drones has been advancing so fast it has been difficult for regulators to keep up. The desire for regulators to go slow is understandable when talking about 50 pound objects that could theoretically fly into electrical transformers, enter airplane engines or drop out of the sky onto children.

American regulators have been more cautious than their counterparts in other parts of the Anglosphere when it comes to the issue of drones. This is in large part why we are seeing testing taking place in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. But overall official commercial drone regulations across several industrialized countries have been fairly consistent. There are also practical limits to how much more aggressive regulators in other countries would want to be.

Having thousands of drones all flying together in an urban setting will take standards about drone to drone and drone to ground communications. The inherent value of one set of standards for UAS air traffic management systems and the outsized role the United States plays in setting standards means we are unlikely to see other countries move forward before NASA finishes its air traffic management testing.

As a result, we are unlikely to see regulations allowing for the wide use of urban commercial drones anywhere in the industrial world until roughly 2020. The UK or Australia might move somewhat more quickly than the United States to actually implement such rules early next decade, but likely only once standards have been effectively worked out.

This, of course, assumes that the public as a whole readily supports and welcomes possibly thousands of potentially noisy drones traveling through their cities, which could cause unemployment to rise among low skilled workers. Popular blowback can slow down the regulatory process or result in any technology simply being outlawed.

There does seem to be a growing understanding of the importance of government policy when it comes to allowing technological innovation. In recent years America’s largest tech companies have significantly increased lobbying spending to deal with the range of regulatory issues they care about.

Header image credit: Wesleyan University News