Large volumes of data, managed properly, are a boon for many industries, including the military. It would not be possible to mount effective military operations without knowing the when, where, and what in deploying resources. Military big data, therefore, helps defense leaders make better decisions, provided it is not “dark data.”

The term “big data” was coined more than two decades ago in a paper presented at the 8th IEEE Conference on Visualization in 1997. The term describes single data sets so large it did not fit into main memory.

At that time, computer memories were in megabytes, with the most powerful running at 128 MB. With even more data coming in at an increasing pace because of information sharing among scientists over the internet, it is no wonder there was so much pressure to develop technology to handle big data.

Today, the cheapest smartphone runs on one Gigabyte (1000 MB) of memory, so ever-growing volumes of data is not as much of a problem as before. To put it in today’s terms, the world data volume in 2013 was 4.4 zettabytes (1 zettabyte = 44 trillion GB), and this might likely rise to 44 zettabytes or more by 2020. However, advanced computer hardware has made data gathering and storing relatively cheap and easy. Additionally, recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technology, analysis has also become much more manageable.

Controversy often surrounds the collection of big data in the military, however. One recent hubbub concerns the collection of visual data using an open source machine learning platform. Drones were the method used in this instance for data collection, or in military parlance, intelligence gathering. The protests were not about the data, per se, but the potential use of ML for aggression.

This sudden vigor against the military use of technology is a curious thing, as using it for Intelligence gathering is hardly a new thing. Granted, the methods used today are different, but the nature and importance of the data itself is not.

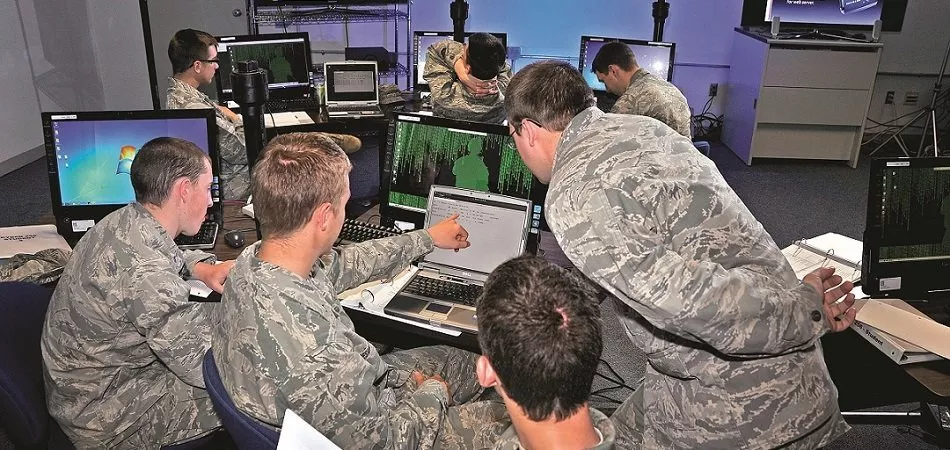

The military continues to gather intelligence in conjunction with the Intelligence Community in various disciplines, which might amusingly be called the “INTs.” There are 17 organizations under the IC, but their paths in the military intersect under the following disciplines:

- HUMINT (Human Intelligence)

- GEOINT (Geospatial Intelligence)

- SIGINT (Signals Intelligence)

- OSINT (Open Source Intelligence)

HUMINT: Human Intelligence

Human Intelligence gathering (HUMINT) is collecting information through personal contact with people. Information takes the form of documents, photos, digital files, and other materials, acquired covertly through unofficial channels or overtly through diplomatic or consular personnel as well as authorized communications with foreign officials. The military might also gain intelligence through enemy interrogation or traveler debriefing.

Most people associate HUMINT with espionage, sometimes jokingly referred to as the second oldest profession in the world, and they would be mostly right. Spies do continue to play a large role in intelligence gathering in this discipline, although it is more complementary to other INTs. For example, a human contact might provide the codes that give SIGINT operators remote access to a system.

The importance of HUMINT in this day of technological advancement is also about context, something AI-enabled surveillance might miss. Having someone on the ground can provide valuable (human) insights in assessing the validity of military targets and observe developments as they unfold.

Data gathered through HUMINT is often in different formats, both analog and digital. It may be audio, video, text, or images, and will have to go through analysis to integrate it with data gathered through other disciplines. AI-based software can tag, organize, and analyze HUMINT data, and one such software currently under assessment by the military is Raytheon’s FoxTen.

Below is a short 1:35-minute video showing the capabilities of FoxTen:

However, AI might soon play a more active role to counteract tracking technology, some designed specifically for spies, others an unwitting tool. The Central Intelligence Agency has several ongoing AI projects, including coming up with ways to deceive tracking devices or map the location of surveillance cameras in hostile or unknown territory.

GEOINT: Geospatial Intelligence

According to the US Code, geospatial intelligence refers to the use and study of images and geospatial data to explain, review, and visually represent terrestrial characteristics and activities. Simply put, GEOINT includes all intelligence gathered from images, videos, and other visual representations taken from the air, on the ground, or underwater.

The value of GEOINT in a military sense is to provide the precise location of objects and activities, interpreting their meaning, and giving it the framework to help make military decisions. The visual data typically comes from satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV), and other surveying technologies.

In most cases, GEOINT data is an integration of geospatial data from different sources to create a three-dimensional representation of the situation. That, in turn, integrates into multi-INT data.

Of special mention in this section is the use of UAVs, more popularly known as drones. The military has been using drones to gather intelligence to support military personnel and operations for many years.

However, increased speed of communications, storage capacity, and ability of machine vision software to operate the drones autonomously has resulted in an overload of data.

The military has over 8,000 drones in its inventory and uses them to good effect. Human staffers have to go through around 1,600 hours of video footage daily, and that is not including the images. The data is invaluable to soldiers on the ground and commanders in headquarters, but only if analysis is accurate and timely.

AI and ML algorithms can analyze videos and detect threats much faster and more thoroughly than human operators can. This is the basis for Project Maven, which currently uses a TensorFlow-based platform to do predictive analytics of drone footage. Following the decision of Google not to renew the AI-development project, the Pentagon turned to start-up Anduril Industries to develop a sensor fusion platform for military drones.

According to the company’s site, with the Lattice AI platform, “only the final information is transmitted back to the user. This allows for a massively scalable mesh network of powerful computers to do the number crunching without ever needing to deploy a server farm or command center.”

SIGINT: Signals Intelligence

Signals Intelligence is information about the actions, objectives, and capabilities of a foreign target acquired through the interception of signals and transmissions. Three subsets of SIGINT exist depending on the type of transmission. COMINT comes from communication systems, ELINT (Electronic Intelligence) from radar and weapon systems, and FISINT (Foreign Instrumentation Signals Intelligence) from weapons systems under development or testing.

The National Security Agency (NSA) typically gathers SIGINT on terrorists, organizations, and persons with international or foreign associations using various methods, but tend to use UAVs more than anything else. It only does so when formally required by the US government. The NSA translates, decodes, and analyzes the raw data into a usable form for non-NSA analysts, such as those in the CIA and IC. These agencies combine the NSA material with data from other INTs to paint a complete picture.

SIGINT has always had more than enough data with which to work as it has such a broad array of sources. Telephone conversations, emails, radio waves, satellite transmissions, wireless connections, and even keyboard vibrations are going on all the time, providing a glut of information to the NSA.

The challenge is to mine the kernels of valuable information from the chaff of random signals. The collection process involves first extracting certain types of signals from layers of signals or conversations from the babble of conversations. After extraction, the SIGINT analyst filters the candidate items to select the ones for retention based on a set of parameters. The NSA then stores these selected items and sends them to the requesting agency for further analysis.

The process is painstaking, and not always as thorough as it can be. It was inevitable that the IC would look to advanced AI and ML technology to make this go faster and better. The main purpose of SIGINT is defense. Knowing the location, intentions, and capabilities of the enemy can go a long way towards preventing harm to soldiers and civilians alike.

However, researchers are increasingly looking to SIGINT to do other things. One is to provide insights that will help them make accurate predictions of future events from the data it gathers.

The IC research arm Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) reached out to data scientists and ML engineers in the academic and commercial sectors to develop continuous, automated SIGINT analysis techniques. Dubbed the Mercury challenge, the prize will go to the algorithm that can effectively “forecast events involving military action, civil unrest, or infectious diseases, specifically in Arabic-speaking countries in the Middle East and North Africa.”

Additionally, the rapid rise of sophisticated cyber and electromagnetic activities (CEMA) and electronic warfare from adversaries is forcing the Army to converge the SIGINT, cyber, and electromagnetic systems into one platform: Terrestrial Layer Intelligence System. The Army is actively looking for proposals to expedite the integration, including development of machine learning software to reduce workloads.

Another potential use of SIGINT technology is to take on a more active defensive role. The ability to detect, identify, and assess the threat levels of a signal, such as radars of surface to air missiles, can spell the difference between mission success and failure.

The Boeing EA-18G Growler keeps soldiers safe by jamming enemy radar signals. There are plans to make the Growler even more effective in defense by integrating AI software that can detect a signal faster and tell the difference between a friendly and hostile one more accurately.

Below is a short video showing the potential of an AI-enhanced Growler:

The world of SIGINT collection and analysis is no longer about intercepting messages and cracking codes for others to take action. With the help of refined data and machine learning, SIGINT is taking on the challenges of rapidly evolving electronic warfare.

OSINT: Open Source Intelligence

As might be intuited by the term, open source intelligence is gathering data from open or publicly available sources for exploitation for a specific purpose. This is a very broad definition of OSINT, and a more detailed one has been difficult to pinpoint over the 50 years OSINT has been in existence. According to RAND Corporation, the reason is that publicly available data sources are always changing. This has become much more obvious since Internet use became common and the explosion of social network use occurred.

Sources of OSINT have evolved over the years. In its first iteration, the most prolific OSINT sources were television, radio, and print media. Back in the day, human operators would go through these data sources manually. Later on, intelligence agencies used commercially off-the-shelf (COT) software to collect, clean, and analyze OSINT data.

Traditional media are still sources for OSINT, but the real powerhouse for data gathering is the Internet. Instant access to readily available and constantly updating data benefits intelligence gathering operations. These include blogs, online newspapers, social networks, video streaming services, forums, and other user-contributed content as well as hidden gems in the backend of websites.

The problem is the sheer volume and complexity of the available data. Data streams from the Internet have layers upon layers of nuances, and analysts have to perform everything from fact-checking to sentiment analysis, always keeping in mind the context of the data.

To add perspective to the enormity of this task, consider social media. On average, Twitter users upload 656 million tweets and Facebook users post 4.3 billion messages a day. This is data from just two social networks. Add to that the daily number of Google searches made (5.2 billion), YouTube videos watched (4 million a minute), blog articles posted, and this amounts to an extremely large quantity of data available to the military.

In the military, analysts have to be able to filter these data streams to identify and classify everything that has any use or impact on military strategies and operations. This may be in relation to certain countries, specific individuals, at-risk populations, weapons, and so on. They have to do this thoroughly, in context with human behavior, and in real time.

This is clearly an impossible task for human operators without serious assistance, and the IC knows it. To address this need, the CIA is currently looking at several projects using AI for OSINT, but not only for analysis. It plans to use AI software and natural language processing algorithms to go systematically through the data streams of social networks and other OSINT sources. The software will select only relevant items, theoretically reducing the OSINT collectors’ workload by 75%.

The idea is to conduct experiments in OSINT and big data gathering and analysis using machine learning in cooperation with private companies over a 5-year period. The CIA announced the Mesa Verde project in May 2018, but no updates are currently available on the proposal.

The commercial sector has not been so circumspect, however. Companies like Google already have tools and APIs specifically designed to handle big data. Below is a short 2-minute video illustrating the features of Google BigQuery:

Big data in the military comes from many sources and information overload is a very real problem. AI and machine learning might be one effective solution, but the powers that be know better than to reinvent the wheel. Looking to commercial and academic institutions to deal with big data is the logical and most strategic move for the military to take.

Header Image Credit: Israel Homeland Security