This article is the fifth installment in the AI FutureScape series, and in it, we discuss what our survey participants said when asked about the role international organizations like the UN should play in hedging against the risk of AI.

We interviewed 32 PhD AI researchers and asked them about the technological singularity: a hypothetical future event where computer intelligence would surpass and exceed that of human intelligence. Such an event would have drastic consequences on society for better or for worse.

Readers can navigate to the other FutureScape articles below, but reading them isn’t necessary for understanding this article:

- When Will We Reach the Singularity? – A Timeline Consensus from AI Researchers

- How We Will Reach the Singularity – AI, Neurotechnologies, and More

- Will Artificial Intelligence Form a Singleton or Will There Be Many AGI Agents? – An AI Researcher Consensus

- After the Singularity, Will Humans Matter? – AI Researcher Consensus

- (You are here) Should the United Nations Play a Role in Guiding Post-Human Artificial Intelligence?

- The Role of Business and Government Leaders in Guiding Post-Human Intelligence – AI Researcher Consensus

Should International Bodies Like the UN Get Involved?

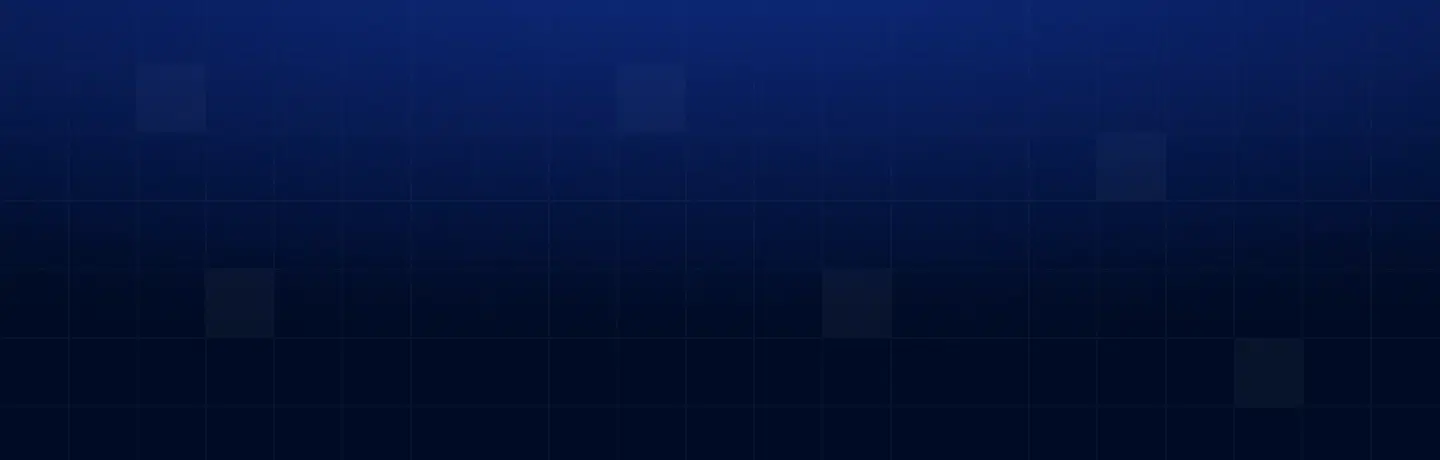

If AI could potentially become a threat, then should the international community coordinate to solve this problem? We decided to ask our experts this question and got an overwhelming yes.

- 63% of respondents believe that there exists some role for international organizations to participate.

- Only 23%, less than a quarter of our respondents, believe that international organizations should not interfere with AI development.

- The rest of our respondents believed that there was a role, but that international organizations shouldn’t do anything yet, and that it was just too hard to tell if they should.

International Organizations Should Intervene in the Trajectory of Intelligent Technologies

The largest category of answers by far was that international organizations need to regulate AI to hedge against the risks:

Let me shift the question to: Should AI be the subject of international agreements? Something as critical to the future of humanity as AI should be on the table for serious international discussion and negotiation. This is as true for AI as it is for any other factor on which humanity’s future depends.- Daniel Berleant

I think some sort of international regulation is necessary with something as powerful as Strong AI, just as it is with nuclear weapons — and for the same reasons. – Kevin LaGrandeur

AI is a tool, and as many tools, it can be used both for evil or good. However, AI has a huge potential for either goal and the implications of an AI system being used maliciously, especially as they become more intelligent, could be disastrous.” – Miguel Martinez

Our respondents are also highly worried about the use of autonomous weapons. These have become a universal issue among AI researchers. An open letter by the Future of Life Institute signed by almost four thousand AI researchers advocates for a ban on autonomous weapons. The controversy of Project Maven also highlights that many in the field do not like the idea of their research being used for weapons.

Yes the UN should have a role in the development of [weaponized] AI. AI controlling weapons systems should never to delegated with the decision to apply violent force. The UN needs a new international treaty to ban weapons that hunt, target and kill people without a human in control to check the legitimacy of targets for every attack. – Noel Sharkey

For those respondents who thought the man-machine merger was a likely scenario, the regulation of neurotech was also mentioned as an issue. One of the worries about human augmentation is that market forces would make anyone who doesn’t augment themselves become obsolete. This is worrisome because people who have religious or moral objections, those who are worried about the risks, and those who simply can’t afford them, will no longer become competitive in society.

Market forces would force people into cognitive prostheses. This, and the content that would be taken from people’s brains, can and should be regulated to limit and slow-down abuse. That immediately affects AI that would depend on such knowledge and information supply. Regulating the latter would help regulate and prevent abuses of the former. – Eyal Amir

A few of our respondents believe that international governance bodies should get involved to not only reduce the risks, but also to ensure we reap the benefits of AI.

There are a substantial number of ways that AI could benefit the world. Its applications in medicine alone could vastly improve our lives. Even though there are a number of risks that must be managed, policymakers should know that there are also real benefits that could make the world a better place.

The societal disruption caused by the increasing use of AI-based systems will have negative aspects…They will also have positive benefit, such as an essential end to illiteracy, which will enable many people who are currently disadvantaged in their interactions with [government] and industry to be empowered. The whole notion of singularity…seems to me to be a distraction from this, the really important question: how do we control the impact of this new technology. – James Hendler

However, there is also the problem of whether or not international bodies will even be effective at governing AI.

There have been discussions amongst experts as to whether or not governments are capable of regulating AI. Emerging technologies are often difficult to regulate to begin with because governments can’t keep up with the pace of technological growth, let alone consider shaping the future trajectory of a technology.

The nature of AI also makes it difficult to regulate. The term AI itself is ambiguous, there’s no required large-scale infrastructure required that makes projects easy to detect, parts of it can be made anywhere in the world, and the software itself is opaque; making it difficult to really know if there is something potentially harmful about it.

If they can… They do seem a bit too slow for the dynamics we are currently observing, so I am not sure they can. – Michael Bukatin

Yes, although hopeful the 21st century will see the creation of far more effective transnational governance mechanisms, directly connected to the global citizenry. The UN, WTO etc are just the best we have right now. – James J Hughes

That will be difficult, as future AI is likely to be decentralized and thus difficult to define as a traditional legal entity. It will not conform to the hierarchical structure that current governing bodies are assumed to conform to, which renders top-down direction or regulation challenging, if not downright impossible. – Patrick Ehlen

International Organizations Shouldn’t Get Involved Yet

Part of these limitations is the lack of concrete areas of work that can be done on this yet. Three of our respondents believed that international bodies should get involved, but not at the present moment.

Before raising alarms, some of our respondents believe it would be best to have some clear idea as to what to do. At the same time many policymakers, and society in general, lack an understanding as to what AI actually is.

Not now, because such bodies have very limited abilities to coordinate, and so should be reserved for very clear and important tasks. We can’t yet identify such tasks regarding AI. – Robin Hanson

Yes, but that should happen after the human society has a better idea about how AI systems work. – Pei Wang

International Organizations Shouldn’t Get Involved at All

10% of our respondents think that because these institutions are ineffective, it would be better for them to not try and govern AI. To them, it would be a waste of time. Or even worse, it could actually cause more harm than good. 7% of our respondents even believe that the stakeholders in these institutions would instead have their own agenda and try to protect their political power:

Those bureaucracies are inefficient and often harmful… They tend to be incompetent as well. Groups of competent people working with, not against, general intelligence, are a much better partner in global development. – Pete Boltuc

Of course not. All political institutions in the world are there to protect a territory (material interest) often related to greed. These institutions have nothing to contribute to AI. They can only slow down progress by injecting paranoia, fear, religious beliefs, ethnic and nationalistic agenda. – Riza Berkan

One of the respondents suggested that there are other more pressing concerns to focus on. For them, issues like nuclear weapons and biosecurity appear to be far more dangerous in the long-run:

No. Nuclear weapons will always be a million times more dangerous than AI. – Danko Nikolic

Too Hard to Tell

One of our respondents took the middle position, saying that it was just too hard to tell. Just like in the previous question, the ability for international governance organizations to effectively manage these risks will depend entirely on our collective choices.

When governments (or political entities such as the UN) get involved, things either go really good… or they go really bad… So, government will likely magnify the effect of AI one way or the other. The question is, will it magnify its [wondrous] and beautiful advantages or will it create another equivalent of nuclear weapons? I have no idea. – Keith Wiley

Analysis

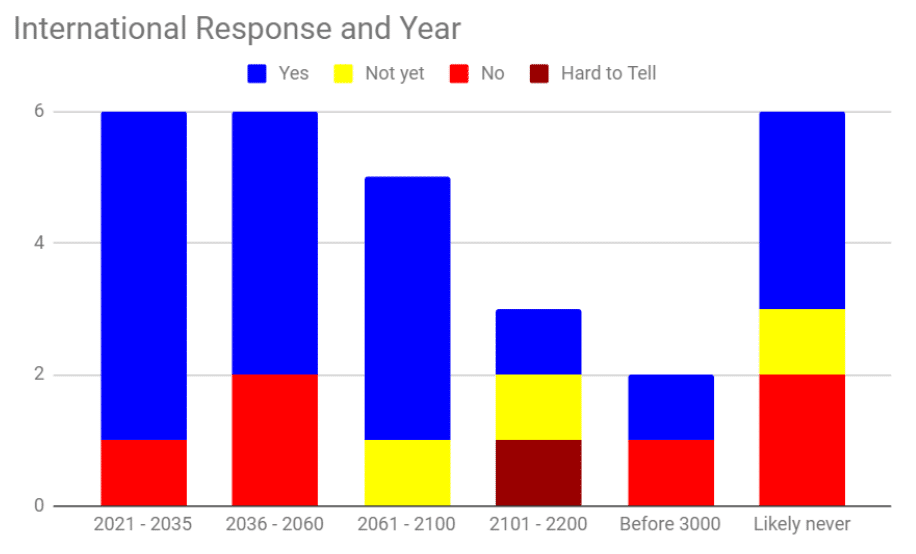

International Response and Year

This section explores the relationship between when respondents expected the singularity and whether they believe international organizations should be involved.

It seems from the graph that respondents who expect the singularity to occur sooner were more favorable to international organizations to play a role in AI. However, respondents are more uncertain in the far future.

From between 2021 and 2035, only one respondent didn’t want international organizations involved. Then, from 2036 to 2060, two respondents didn’t want international organization involvement. This makes sense because if the singularity was going to happen sooner, a response from the international community may be more urgent.

This trend, however, changes between 2061 and 2100, where only one respondent said that the international community should not get involved yet. The trend from 2021-2060 continues from there, where 2101-2200 was split equally between “yes”, “no,” and “hard to tell.”

Another interesting finding is that half of those who didn’t think the singularity would ever happen still advocate for international organizations to get involved. This is because even current levels of AI pose many problems for society, such as autonomous weapons and deep-fakes.

Taking a deeper look at the data, all of the responses between 2021-2060 that said international organizations should not get involved was due to them being perceived as ineffective. At the same time, two responses said that international organizations should get involved, but will likely be ineffective.

If we assume that the perceived lack of effectiveness is representative of the AI community as a whole, there’s a somewhat large population of researchers who do not think that international organizations will be effective at resolving these problems.

The only other reason stated outside of the singularity likely “never happening” category is that international organizations would simply promote their own agenda, which is in the “before 3000” category. So, it would seem that among respondents who said the singularity would happen, institutional effectiveness is their main concern regarding international involvement.

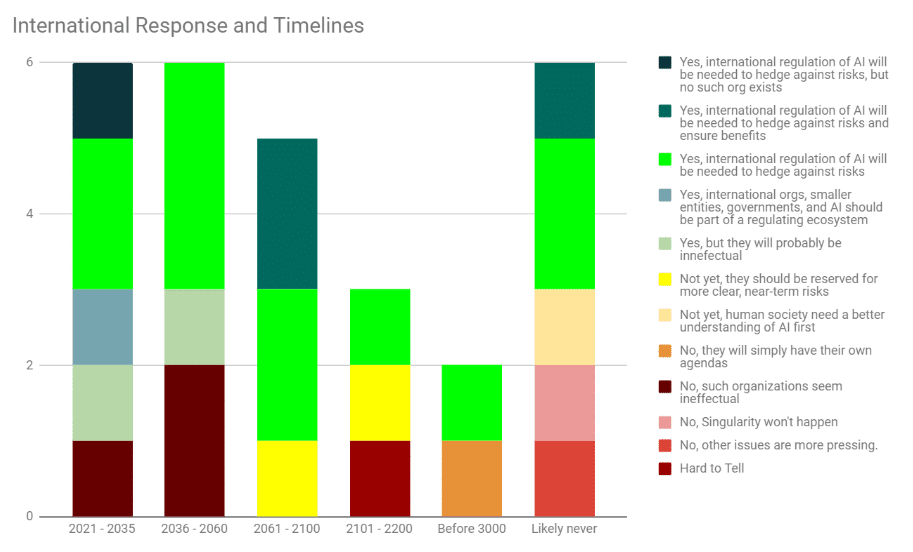

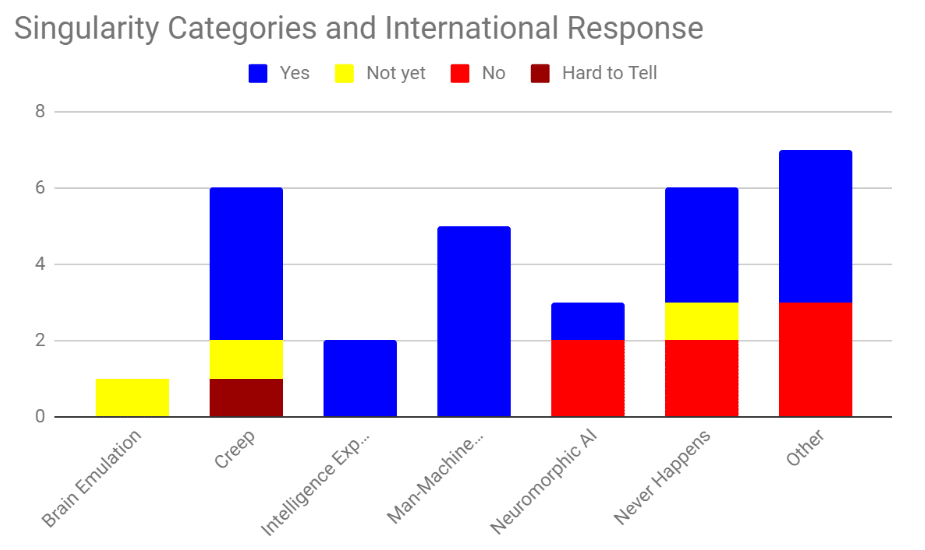

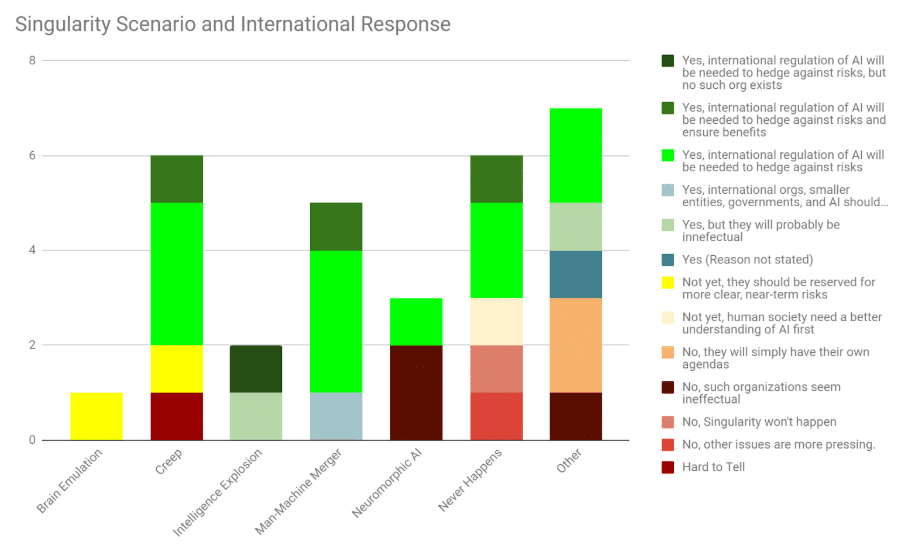

Singularity Scenarios and International Response

This section looks at the relationship between the different paths into the singularity and what respondents said about the role of international organizations.

From this graph, we can see that most of the categories, except the other and never happens categories, overwhelmingly advocate for there to be some form of governance by international organizations. The exception is neuromorphic AI, where two out of the three respondents said that international organizations should not govern AI.

A further look at the data shows that the two respondents in neuromorphic AI who did not think international organizations should intervene believe that these organizations would be ineffective.

Looking back to the originally-typed responses, the neuromorphic AI respondents were pessimistic about the organizations themselves and does not seem to be unique to its ability to govern AI. The most likely explanation for why this group is more pessimistic is that this is a consequence of the low sample size of the survey.