Both artificial intelligence and robotics have been improving over the past few years. Large companies are betting billions that in the near future we will have cars that can drive themselves, drones that can fly themselves to deliver packages, automatic fast food chefs, AI personal assistants, manufacturing robots that can train themselves and other robots, etc.

This has raised some big questions, including:

What happens if a new technology causes millions to lose their jobs in a short period of time, or what if most companies simply no longer need many human workers?

In the United States our current society is built on the premise that companies and government need human workers to function, and most able bodied adults can perform tasks companies would pay for. Everything from the way we design our transit systems to allow for daily commutes to work, to how we structure health insurance and how set monetary policy is based on this premise. The Federal Reserve’s core function is its dual mandate: to maximize employment and keep prices stable.

One of the most important policy decisions based around this concept of mass employment is how the government is funded. Roughly 80 percent of all federal tax revenue comes from income or payroll taxes. If even a modest segment of workers are displaced, the impact on government budgets could be substantial.

To deal with this possible problem the world’s richest man, Bill Gates, has floated the idea of a robot tax. Gates has suggested we tax robots at a rate similar to what we would’ve taxed the workers so tax revenue could pay for more employment in education and elder care. The idea is also to slow down the speed of the technology’s adoption, to give society more time to adjust.

This article is going to give an overview of where a robot tax stands as a policy from multiple angles:

- Whether a robot tax might even be needed. I.e. how quickly are robots going to replace workers

- How such a robot tax might work.

- What are the arguments for or against it.

The first big policy question about the robot tax is if it would even be needed in the next few decades.

Background Insight: Robotic Automation and the Job Market

Gates obviously thinks broad job replacement will happen relatively soon. He told Quartz that, “warehouse work, driving, room cleanup, there’s quite a few things that are meaningful job categories that [will be replaced by machines], certainly in the next 20 years.” However, estimates about the rate and speed of automation in the next several years vary greatly.

Gates is not alone in his fears. A 2013 analysis by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne concluded about 47 percent of total US employment is in jobs that are at high risk of computerization, possibly over the next decade or two. As Carl Benedikt Frey explains in the video below, he believe automation not trade will be the main driver in changes in employment:

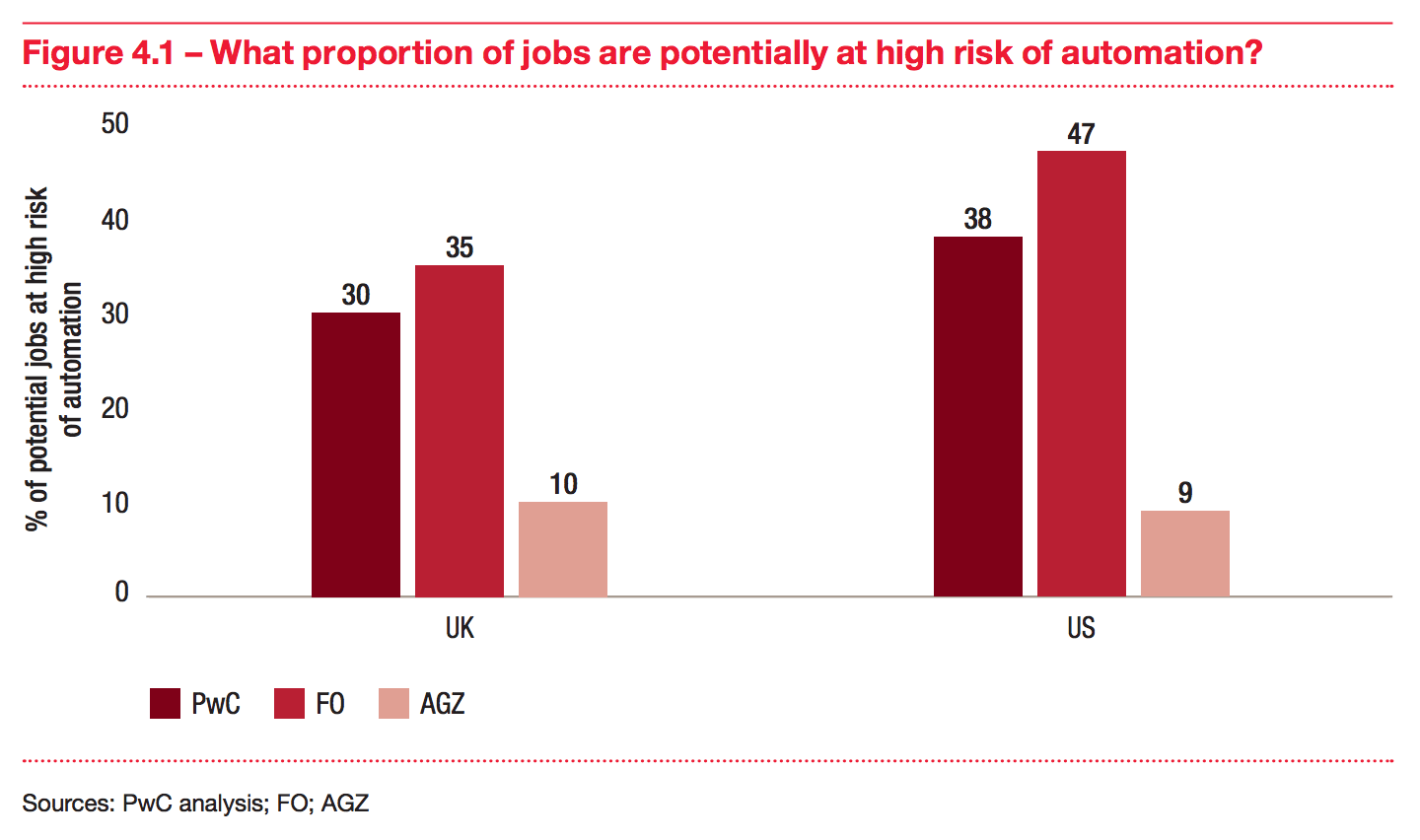

Similarly a 2017 analysis from PwC found 38 percent of jobs in the United States “could potentially be at high risk of automation by the early 2030s.” They found transportation, manufacturing, wholesale and retail to be at the greatest risk.

On the other hand Melanie Arntz, Terry Gregory, and Ulrich Zierahn published a paper in 2016 which concluded that just 9 percent of jobs in the United States are at risk of automation.

The following graphic shows how PwC charted compares these three analyses:

(Include this graph or just a graph based on this data from page 3 of the united states https://www.pwc.co.uk/economic-services/ukeo/pwcukeo-section-4-automation-march-2017-v2.pdf)

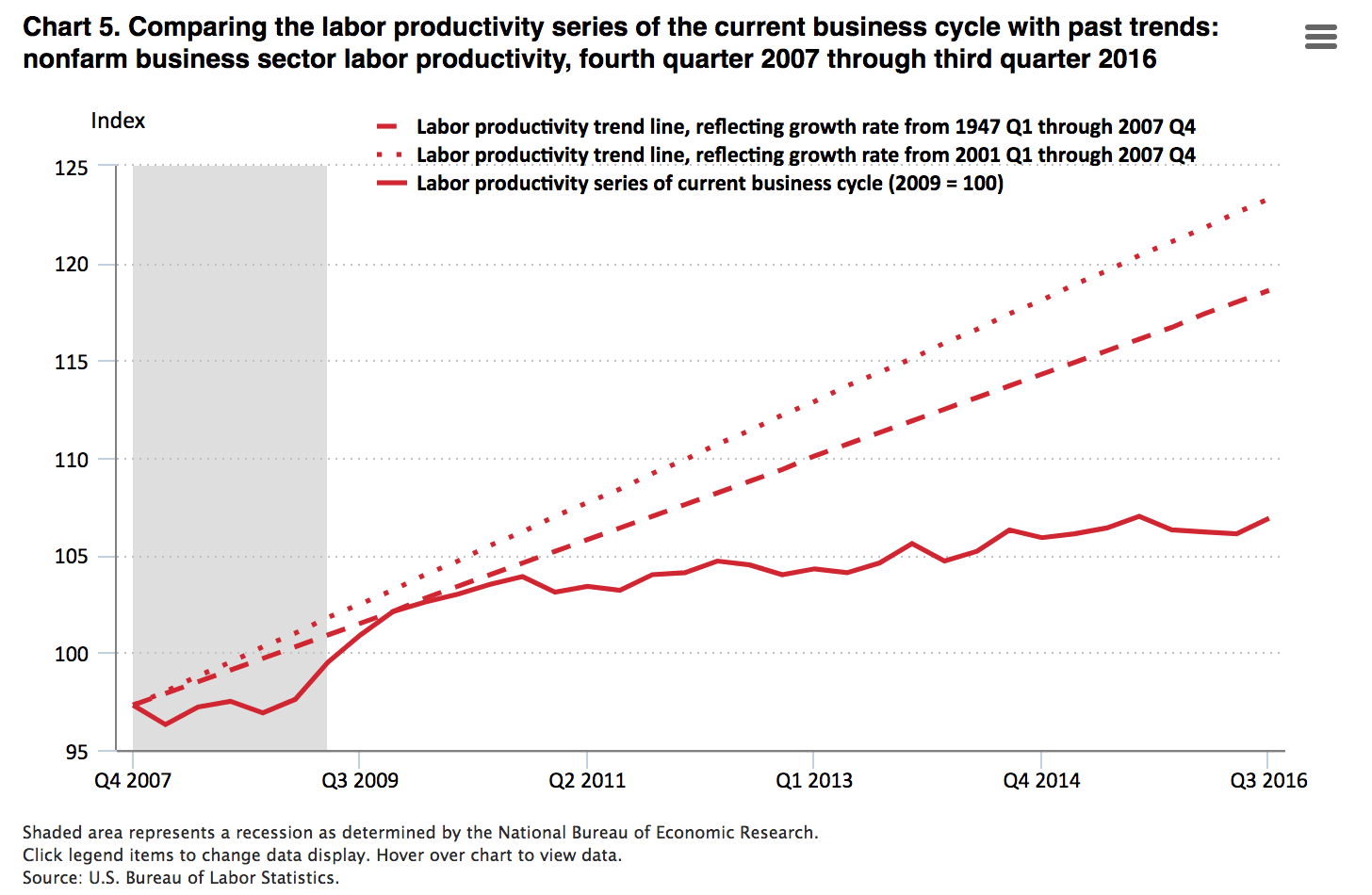

The economist Dean Baker has been skeptical that there is good evidence automation will soon lead to mass unemployment. He points to data on productivity, which in theory should be going up if we are currently seeing big advancements in automation spread throughout the whole economy. “It’s averaged just 1.2 percent annually in the last 10 years and 0.6 percent in the last five years. By comparison, productivity growth averaged 3 percent in both the decade from 1995 to 2005 and the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973.”

Dean doesn’t dispute the idea we could theoretically reach a tipping point in AI where technology could lead to mass job displacement at some point in the future, but he thinks the current focus on robots taking people’s jobs is misdirected at this time. Looking at current productivity numbers, a tax that disincentive investments in productivity would seem misguided right now.

There is broad agreement at least some jobs will be eliminated by technology, but the United States has been able adjust to technology eliminating some jobs over the past several decades. There are less travel agents now compared to 30 years ago but more yoga instructors.

That is why the rate at which it will happen is so important. Will it happen at a rate our current system can already manage, or at some point in the near future will it turn into a torrent of change requiring new government policy solutions?

Could a Robot Tax Work?

The first step is policy makers need to be convinced that automation will lead to mass unemployment is a serious and potential problem. It is only once policy makers think there is a problem does talking about the design possible solutions become relevant.

At this point the idea of what a “robot tax” would be or how it would actually work in practice is very nebulous. There are a few ideas which have been called a “robot tax,” but they very significantly in design and scale. For example South Korea relatively modest move to reduce the tax incentives for investment in automation a being called a “robot tax,” but that is nowhere near the scale what Gates is envision for his “robot tax.”

Gates simply suggested that “some of it could come on the profits that are generated by the labor-saving efficiency there. Some of it could come directly from some type of robot tax.”

A segment of a proposed motion in the EU parliament which was rejected simply called for looking at, “levying tax on the work performed by a robot or a fee for using and maintaining a robot should be examined in the context of funding the support and retraining of unemployed workers whose jobs have been reduced or eliminated.”

Levying a fee on each robot sounds much easier in theory than it practice. How would we define “robots” for these tax purposes? What separates a tool from a robot or a complex computer program from AI? For example, a backhoe replaces human ditch diggers, but few people consider that a “robot.”

Is a vending machine a human-replacing robot? What about a vending machine that can automatically alert its owner when it is out of a product? What about a vending machine the size of a small store that can automatically stock itself and answer complex questions from customers?

If a country did try to place a fee on actual robots, it is likely it would be difficult for some companies to avoid the tax. Manufacturing robots, self-driving cars, delivery drones, and anything that looks like a classic “robot” or clearly replaces a specific category of job would likely be hit.

But there are a lot of marginally robot-like tools that manufacturers would aggressive lobby policy makers to exclude from the tax. Alternatively, manufacturers could modify the tools just enough to exploit some loophole in the definition of a robot.

To get a sense of just how complex and protracted a legal question “what is a robot” could turn into, one needs only look at the legal fight (and huge tax repercussions) over whether Marvel’s mutants are “humans”.

For years, the United States has taxed the importation of “dolls,” which are representations of humans, at roughly twice the rate it taxes the import of “toys.” So Marvel entered into a decade-long legal fight to prove its characters like Wolverine and Spiderman weren’t technically “humans” and so their action figures would be taxed at the toy rate.

One big impact of an attempt to tax specific robots might not be slowing innovation but redirecting it towards almost-robots. Right now many companies are hyping how much they are using AI and machine learning to investors, but in a country with a robot tax you could easily see the opposite: companies using very AI-like programs they refuse to admit are true AI.

The difficulty of defining “what is a robot” might putting a tax on every robot a logistical and legal nightmare. As a result any “robot tax” concept might take on the form of something less direct.

For example South Korea reducing the tax incentives for investing in automation is called a robot tax. It is possible to imagine the “robot tax” taking the form of higher taxes certain types of productively enhancing developments and/or the form of big tax breaks for companies that keep the size of their workforce stable each year.

A “robot tax” could also maybe take the form of a tax that target companies with high profits/revenue but small workforces. Something like a worker to profit ratio could serve as a proxy for deciding what company are making use of a lot of automation.

All of these less direct “robot tax” ideas get around the question of defining what is a robot but they all have their own implementation challenges and possible drawbacks.

Arguments “For” and “Against”

For

The argument for some variety of a ‘robot tax’ is based in the belief that automation will cause mass employment displacement in the near future (or at least massive economic inequality). Computer development hasn’t been linear; it has been exponential. We could reach a tipping point where machines suddenly become better than people at a whole range of tasks. The last major employment displacement, the industrial revolution, caused decades of falling wages and significant social unrest.

A robot tax would accomplish two goals.

- First, it would slow down the deployment of automation to give society more time to adjust to the possible employment displacement.

- Second, it would raise money needed to keep government programs going and to pay for programs to deal with this displacement, such as increasing the number of teaching jobs.

Against

The arguments against a “robot tax” are numerous, and many have been touched on in other parts of this article. Mostly they come down to questions of is it needed, can it even be implemented, would it cause more problems than it tries to solve, and is there a better way.

Is it needed? – Some analysts don’t believe automation will have as big an impact on employment in the near future. With the current weak productivity numbers, talking about policies that would disincentivize productivity gains seems like a bad idea. Meanwhile, automation does eliminate some jobs but also creates new ones; it is possible the rate of change will be manageable.

Could it be implemented? – Trying to define what is or is not a “robot” for the purposes of taxation would be an extremely difficult task and would turn regulations over the issue into a never-ending legal battle. The different states and levels of the United States government can’t even agree on what legally constitutes a sandwich, a question that requires far less technical expertise than defining what is an AI or robot.

Could it backfire? – Andrus Ansip, the European Commissioner in charge of the bloc’s push for a Digital Single Market, argued aggressively against the robot tax, saying if the EU adopted a robot tax, “somebody else would take this leading position.”

Unless all countries on Earth adopted a robot tax, you run the risk of robotics companies moving their operations from countries with a robot tax to nearby ones without. Instead of getting money from robots and slowing their deployment, the country with a robot tax could lose out on the cash and cause the development to occur elsewhere.

Is there a better way? – If mass automation does cause dramatic job displacement, the money that was previously spent on wages for these jobs doesn’t just go away. It should result in high corporate profits and capital gains. Instead of trying to figure out how to tax specific robots, countries could just try other ways to increase revenue from corporations.

This could be accomplished via high corporate taxes and capital gains taxes. Noah Smith suggested an alternative to the robot tax could be developing a sovereign wealth fund. The government could buy up shares in companies, or it could replace the entire corporate tax structure with the requirement that all companies give the government a set percentage of shares.

Concluding Thoughts

For businesses, the idea of a robot tax is new and mostly unformed, so there is little threat of it happening in the next few months or even years. But it is starting to gain the attention of policy makers in Europe and the United States.

Earlier this year Benoît Hamon, the Socialist candidate for president in France, campaigned on the idea. San Francisco Supervisor Jane Kim, launched the Jobs of the Future Fund to advocate in California the idea “if an employer replaces a human worker with a robot or algorithm, he or she would pay a tax.” And recently UK Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn called automation an urgent challenge that must be managed – see the video below from 49:36 to 51:55:

The regulatory and legal nightmare that would likely result from any effort to define what is a robot, and trying to place a specific fee on every type of robot, makes a broad-based, true robot tax seem very unlikely. When it comes to broad-based policy, it is likely the idea of a robot tax will end up being used as a way to simply refer to the general idea that automation could cause mass employment displacement.

Any big policy change that would result from that opinion is in practice more likely to take the form of restructuring how much a government taxes payrolls versus corporations and capital gains.

That doesn’t mean we won’t see some targeted robot taxes. While a fee on every possible type of robots would be a massive legal challenge, it would be fairly simple to tax a few very specific types of robots.

I think the most likely short term concern for companies about discussions around a robot tax is that a few high-profile industries could be hit with a tax at a national or local level. For example, self-driving taxis, self-driving trucks, and delivery drones are all very easily seen as job-taking “robots” by the public. Local legislatures could target these robots with a special fee to fund retraining of drivers or to make up lost revenue. These taxes would be easy to understand and give legislatures the chance to say they are doing something.

For the AI and robotics industries overall, the idea of a robot tax creates an interesting collective action problem. On an individual level, any one company benefits from playing up the labor-saving benefits of their technology and making very optimistic claims about how quickly it will be adopted. Yet the more these industries as a whole make bold predictions about rapid transformation, the more likely they are all to be hurt by a political backlash.

Header image credit: LeverHawk