Deepfakes have made their way onto the radar of much of the First World.

As with many technology phenomena, deepfakes have their origins in pornography editing (the Reddit page that originally popularized deepfakes was banned in early 2018).

In April of this year, I was asked by UNICRI (the crime and justice wing of the UN) to present the risks and opportunities of deepfakes and programmatically generated content at United Nations headquarters for a convening titled: Artificial Intelligence and Robotics: Reshaping the Future of Crime, Terrorism, and Security.

Instead of speaking about the topic, we decided it would be better to showcase the technology to the UN, IGO, and law enforcement leaders attending the event. So we took a video of UNICRI Director Ms. Bettina Tucci Bartsiotas, and created a deepfake, altering her words and statements by using a model of her face on another person.

This project involved a tight time schedule, very little budget for the project, and only one minute of data. Programmatically generating video and voice with open-source technology isn’t easy with these limitations, but the video came out reasonably well all things considered. After the initial demo is a breakdown of the broader concerns of programmatically generated content, which will be the focus for the bulk of this essay:

The United Nations presentation had to be short, and some of my initial remarks about government control of the virtual world – and about AI propaganda newscasters China – were asked to be removed.

In this essay, I’ll aim to flesh out the idea of programmatically generated everything, and some of its short and long-term considerations. I’ll address my points in the order presented below:

- The Varieties of Programmatically Generated Everything

- Positive Applications

- Negative Applications

- Near-Term Threats

- Long-Term Considerations

We’ll begin by examining the range of programmatically generated content:

The Varieties of Programmatically Generated Everything

There are an almost unlimited number of AI-created content – from architectural designs, to video games, and beyond. I’ll explore a number of the more developed programmatically generated content types, with context on the speed the technology’s development when possible:

Faces

This deepfake video of Barak Obama and Jordan Peele helped to bring the technology to public awareness. It’s also a humorous and apt introduction to what the technology can do:

The Dali Museum recently used extensive footage of Salvador Dali, and details about this voice, quotes, and facial gestures, in order to programmatically generate a full virtual replica of Dali. This technology is still nascent, but the results are magnificent compared to what might have been possible just a few years ago:

But AI isn’t just impersonating faces of the living, or recreating those of the dead. AI is also helping to programmatically generate entirely new faces, virtual “people” who have never actually existed. This technology is getting better every few months, to the point that programmatically generated faces that nearly impossible to tell apart from real photographs. The faces on the left were programmatically generated in 2014, and those on the right were generated in 2019:

Human Bodies and Movement

Algorithms trained on human movement can take a human model and “make them dance”, by moving them in line with a movement model, as in the excellent video from Caroline Chan below. At a high resolution this technology is still clunky, but within two years there should be close to no difference between a video of real dancing, and of programmatically generated dancing:

Much less sophisticated modeling can be done with more limited video data:

Future Events

MIT CSAIL has trained algorithms to predict future video frames based on still images, by training a deep learning system on video footage of similar videos, such as crashing waves on a beach:

Virtual Environments

NVIDIA has made it possible to take a simple series of photographs and turn them into an immersive 3D virtual world. By training a machine learning system on countless cityscapes with LIDAR and image data, a single image can be extrapolated into an entire 3D scene:

NVIDIA also has created a program that can turn a simple Microsoft Paint-like image into a rich nature scene, including trees, rock, grass, water, and other natural elements. Within two or three years it is reasonable to suppose that these images will be indistinguishable from photographs:

Artwork

All of these paintings below were made by Rembrandt. Except for the one on the bottom right, that was programmatically generated by an AI system trained on Rembrandt’s other paintings. The differences are essentially indistinguishable:

Music

AI-generated music has improved significantly in the last two years, even if most of it isn’t very good. Here’s a track purportedly generated by AI from AIVA, a Luxembourg-based startup:

We should expect that these musical applications will develop significantly in the years ahead, to the point where nontechnical users can iterate and develop new musical creations beyond those we know today.

Give it 4 years. Alternatively, put @OpenAI on it for months.

Within 10 years many of the ‘best’ songs/music may be written w/aid from AI.

Within 20 years people will be able to listen to programmatically generated music created just for them, their mood/preferences. https://t.co/Ei62HIFxKG

— Daniel Faggella (@danfaggella) April 27, 2019

The Big Shift

The change here involves more than easy impersonations and interesting new forms of art. The big shift can be summed up as follows:

For five or six generations, images, audio, and video were artifacts of events that actually happened. This will soon no longer the case.

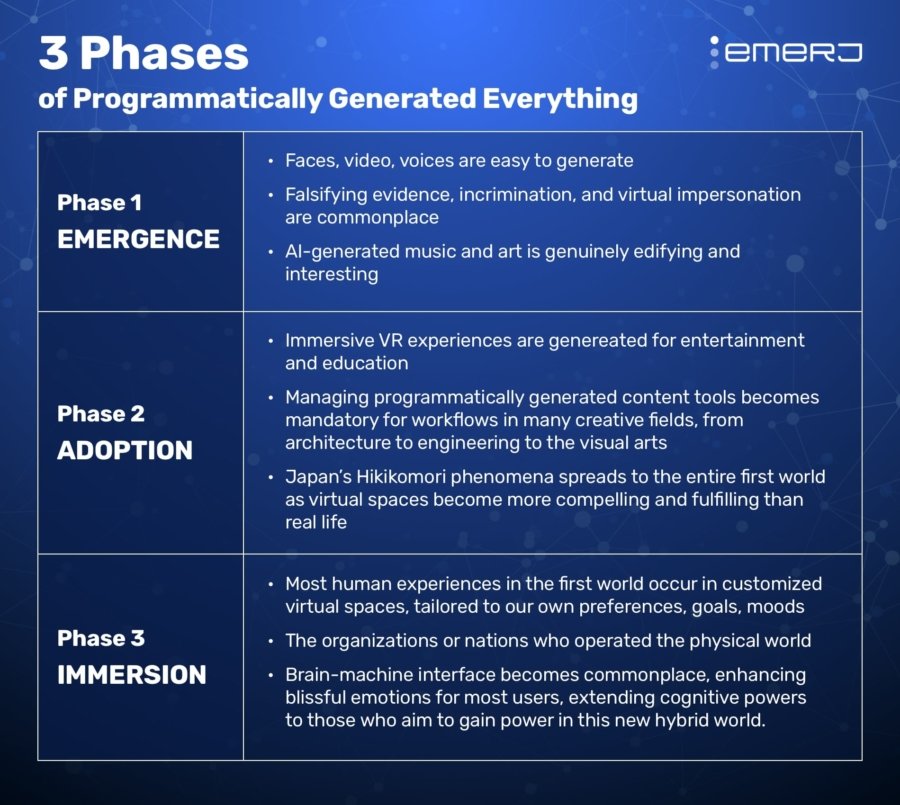

It’s a harbinger of a much larger transition towards virtual worlds and programmatically-generated experiences. I think it’ll go down something like this:

Before diving into the more far-reaching implications of these technologies (which interested readers can explore in my previous essay called Lotus Eaters and World Eaters) – I’ll explore some of the potential positive and negative implications of these technologies:

Positive Applications

Imagine having a machine creating tens of thousands of possible designs for an architecture project, or for a company logo, and distill these options down to a dozen options based on your preferences:

- Young students in the near future may be able to learn American history by speaking to a virtual George Washington.

- Imagine being able to see exactly what clothing or hairstyles would look like on your body by looking in an AI mirror.

- Imagine having a programmatically generated project manager who can stay on top of tasks and teams perfectly, calibrating requests and interactions based on the preferences of each team member.

All of us wish to access more than we can today – to explore, to see, to feel, to experience – more. If we are optimists, maybe to become more and contribute more. In Emerson’s words:

This quasi omnipresence supplies the imbecility of our condition. In one of those celestial days, when heaven and earth meet and adorn each other, it seems a poverty that we can only spend it once: we wish for a thousand heads, a thousand bodies, that we might celebrate its immense beauty in many ways and places.

AI-enabled virtual worlds will encourage and allow for much of this kind of exploration, learning, and experience. But it will also be a force of necessity. Just like the internet today, many of us won’t be able to live or work without technologies like this in the decades ahead.

Programmatically generated tools for architecture, for programming, for engineering, and more. And more than pragmatic, the technology may drag us to worse conditions, or be used in overtly malicious ways.

Negative Applications – Beyond Deepfakes

- Imagine advertising so captivating and real-time customized to your preferences that you can’t possibly ignore it.

- Imagine virtual worlds and digital platforms so stimulating and rewarding that you never want to leave them, or where your behavior can be subtly molded to purchase products, engage with advertisements, or be indoctrinated with political beliefs – all without your being aware of it (what Jaron Lanier has called the “ultimate Skinner Box“).

- Imagine programmatically generated news anchors who can say exactly what they need to say to each county (or if via the internet, to each individual user), molding the beliefs of the public to behoove the ruling party:

- Imagine young people living the majority of their time (entertainment, learning, socializing) in virtual worlds, losing the ability to socialize with other real humans who are not programmatically generated to fulfill their own desires (MIT’s Sherry Turkle has been exploring these topics for years, listen to our interview with Turkle here).

It may be easier to conjure images of dystopias than utopias, and I’m not here to paint this technology primarily in a bad light.

Near-Term Threats

Programmatically generated content presents a number of important challenges to the existing political order. I’ll highlight three present threats worth noting:

The weakening of democracy and freedom

We assume that democracies are the strongest, the post peaceful, the most prosperous form of government. We assume that the quality of life and the power of a nation will correlate to how democratic that country is. This is not the case.

- Democracies can be tampered with from outside, from nations who aren’t so tamper-able themselves. Russia collaborates with Chinese Great Firewall security officials in implementing its data retention and filtering infrastructure. These nations have an advantage in bringing programmatically generated into open democracies, while being far less vulnerable to the same kind of manipulation (due to one-party governments with top-down control).

- Democracies can be tampered with from inside as rival factions and groups aiming to vie for power. At this time of shamefully high political fragmentation in the United States, there are certainly extreme factions on both sides who would consider it justified to release a programmatically generated video to accuse political enemies of doing or saying something terrible. If nothing else, this could simply be done to make truth inaccessible, and stir discord.

Totalitarian regimes dominating the virtual world

One-party totalitarian states could mold the minds of their citizen to marshall them towards party goals. From programmatically generated newscasters, to subtle propaganda insertions in various online media, to AI-based monitoring of citizens activities in the virtual world – dictatorships can encourage loyalty, nationalism, or harsh sentiment toward enemies.

The ability to pool the resources of the private sector and academia towards the goals of the ruling party (economic and military predominance) may drastically improve the critical AI capabilities of totalitarian states.

Encouraging closed information societies

I fear that a total lack of trust in media, combined with persistent interference in political affairs and public opinion by other nations, will turn currently open societies into closed and paranoid ones. Nations may become much less trusting of one another, and may be forced out of necessity to set up information protocols unique to their country, a system they can trust with critical information.

- Mistrust of outside info implies mistrust of the “other”. The growing cosmopolitan spirit might be clouded by virtual barriers that enhance a feeling of in-group and out-group, friend and enemy. If there is any hope for a peaceful 21st century, I believe that a fading sense of tribal “other” is high on the list – and drastically decreased trust could reduce this critical element to peace and collaboration to overcome humanities grand challenges.

- A lack of trust between nations might more easily lead to conflict. In addition, nations will all be fighting for a more secure hold over the whole virtual world for themselves (see Substrate Monopoly below in this essay, and see my essay on the Final Kingdom).

Long-Term Considerations

The Great Virtual Escape

Given a long enough time horizon, human beings will gradually spend more and more of their time in virtual worlds. Already, it might be said that many people live most of their lives online. Many people have most of their communication online, most of their entertainment online, most of their learning online, most of their work online. This allows for convenience and a greater “reach” for our needs to socialize, to learn, to work – but it may also be a kind of crutch for genuine social issues.

Japan’s hikikomori phenomena has led to many young people (mostly men) isolating themselves in their rooms, choosing video games, online interaction, and pornography over engagement with the real world. Many of these men begin their hikikomori experience in adolescence or early adulthood, and remain in the homes of their parents for decades, rarely leaving their home – and retreating entirely from work or real-world friendship. In the last two decades, as hikikomori has proliferated, so have suicide rates in Japan.

In the United States, middle age (mostly white) men are committing suicide in record numbers since roughly 1999. This has coincided with increased rates of so-called “deaths of despair” from drug overdoses and alcoholism.

People seek video games, drugs, or suicide because they offer an escape.

“Escape,” I think, is the key word here.

As traditional modes of life are evaporating the face of fast-paced technological change, workplace evolution, and social trends – meaning becomes harder to find for many. I have argued that Japan’s hikikomori are the canary in the coal mine of the entire first world – and that escaping meaninglessness, anxiety, and depression will increasingly occur through virtual means. If friendship, adventure, and some semblance of meaning can be achieved through hyper-personalized, programmatically generated experiences – very few people will turn down these experiences for the “real” world.

To millennials, the virtual world is quite “real.”

Younger generations are even more enmeshed with the virtual world. 61% of Gen Z can’t go more than 8 hours without being online. Gen Z is 25% more likely than Boomers and Gen X to choose a digital world where websites or apps can predict and provide what users need at all times. Customized virtual worlds are what young people want – and being online or on digital platforms, all day is what young people do.

What do you think the experience of the even younger generation will be?

For the next generation, the virtual and digital world will be more “real” than the physical world – and within 20-30 years I predict that human beings will spend vastly more time in programmatically generated, customized online worlds – with many of them wholly ignoring the physical world outside of the practical necessities, which will at some point boil down to little more than nutrition intake, waste elimination, and some kind of basic hygiene.

Regarding the digital escape, we’ll have to ask ourselves:

- Should we encourage young people to spend less time with technology, and to engage more with the physical world – or are they better suited (for jobs, for friendships, for life) through the same amount of virtual immersion as their peers?

- Is it possible to make the transition into a mostly virtual world a positive overall impact for humanity? How?

Substrate Monopoly

The whole of the “programmatically generated everything” paradigm ultimately leads to the question of who is in control. In the next 20 years, this long-term battle for ownership over the virtual world will definite international politics and big business. In my full essay The Substrate Monopoly, I sum it up this way:

In the remaining part of the 21st century, all competition between the world’s most powerful nations or organizations (whether economic competition, political competition, or military conflict) is about gaining control over the computational substrate that houses human experience and artificial intelligence.

I won’t go into vastly more detail in this essay, for the sake of time – but at 19 minutes into my interview for The Simulation, I explain some of the basic dynamics of why I believe the virtual world will become the pinnacle of power in the 21st century, and how it might play out:

Regarding the substrate monopoly, we’ll have to ask ourselves:

- Should a single government or company control the virtual world? Should there be any limits to what people can access or experience in this virtual space?

- Is it possible to assemble a global consortium of nations to manage the virtual world to be fair and safe for all people?

- Will countries with total virtual control and a firm grasp on the minds of their citizenry (China) have a distinct competitive advantage in wielding their virtual citizenry towards a ruling party’s goals of prominence and power?

Resources

- Sherry Turkle et al, Simulation and its Discontents (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2009)

- Center for Generational Kinetics and WP Engine, The Future of Virtual Experiences: How Gen Z is Changing Everything

- Dawn of the New Everything – with Jaron Lanier | Virtual Futures Salon YouTube Channel