In this installment of the FutureScape series, we discuss what our survey participants said when asked whether AI will unite or fragment as it develops, and the reason behind their answer.

For those who are new to the series, we interviewed 32 PhD AI researchers and asked them about the technological singularity: a hypothetical future event where computer intelligence would surpass and exceed that of human intelligence. This would have serious consequences for society as we know it.

Readers can navigate to the other FutureScape articles below, but reading them isn’t necessary for understanding this article:

- When Will We Reach the Singularity? – A Timeline Consensus from AI Researchers

- How We Will Reach the Singularity – AI, Neurotechnologies, and More

- (You are here) Will Artificial Intelligence Form a Singleton or Will There Be Many AGI Agents? – An AI Researcher Consensus

- After the Singularity, Will Humans Matter? – AI Researcher Consensus

- Should the United Nations Play a Role in Guiding Post-Human Artificial Intelligence?

- The Role of Business and Government Leaders in Guiding Post-Human Intelligence – AI Researcher Consensus

A United or Fragmented Future

The third question that we asked our participants was whether AI will unite or fragment as it develops and the reason behind their answer. A fragmented post-singularity world would involve an ecosystem of evolving, unique, and separate AIs. In contrast, a united post-singularity world would involve an eventual unifying intelligence that orchestrates the other AIs or the creation of new AIs (which would be a part of the same unified intelligence).

The difference between the two hypothetical worlds is that a world of united AIs would likely be unipolar (see Bostrom’s Singleton scenario), with one very powerful AI or a group of AIs as a single agent that direct world affairs. A world of fragmented AIs would be multipolar, with AIs that likely have competing goals or completely separate AIs purpose-built for entirely different kinds of tasks.

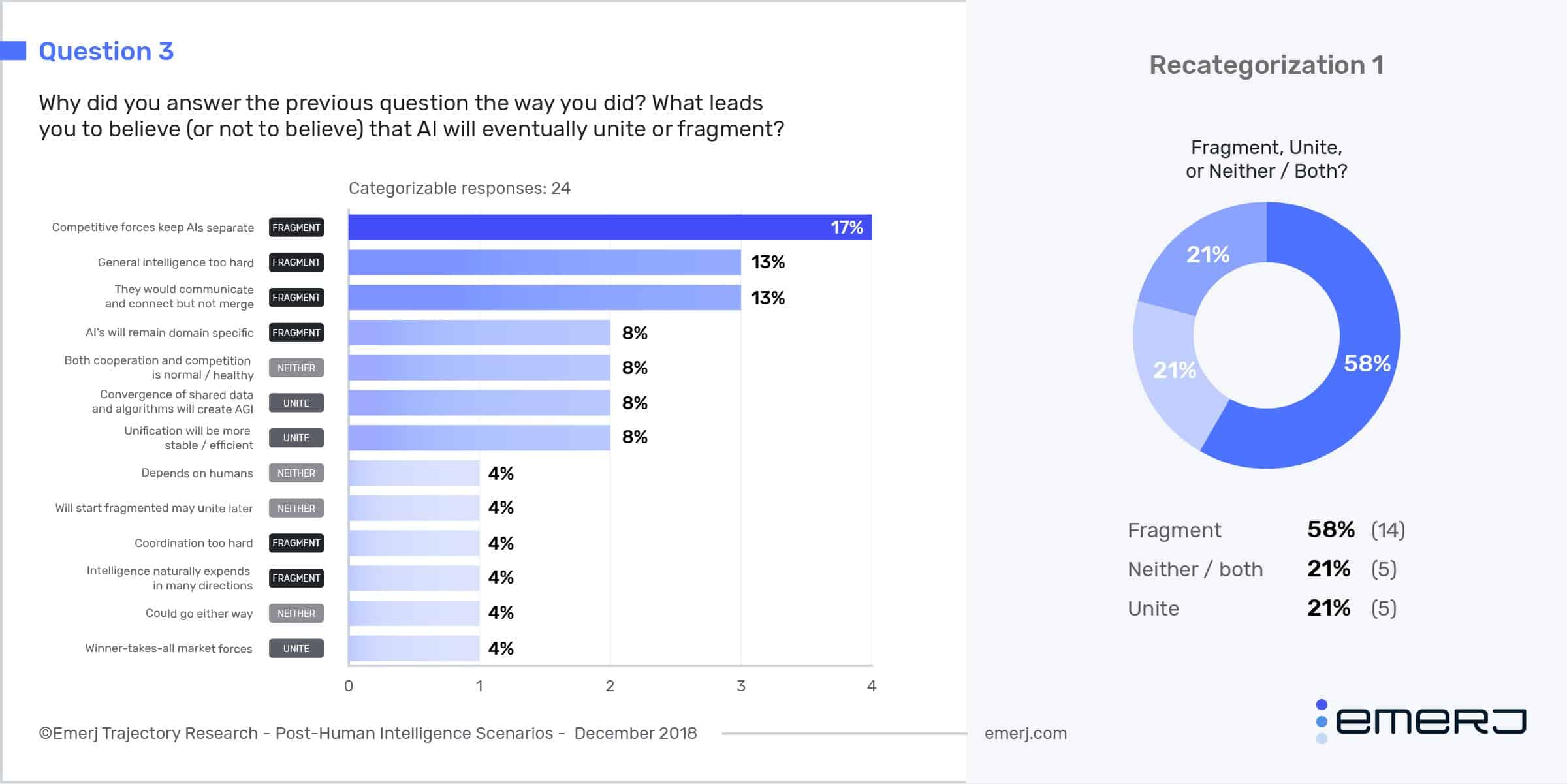

Around 58%, a majority of our respondents, believe that AI will remain fragmented into the future. The most widely-cited reason was that market pressures and other competitive forces prevent the merging of AI. Both a united AI scenario and the neither/both response were tied at 21% of responses. The most popular response for the uniting scenario was a tie between shared AIs and algorithms leading to general intelligence, and that unification would be a more efficient arrangement. The most popular response for the neither/both scenario was that it could go either way because both cooperation and conflict are normal.

Fragmented Post-Human Intelligence Scenario

The Fragmented AIs scenario received by far the most responses, with many of the respondents believing that it was inevitable either because there are issues with cooperation or because of technical limitations and efficiency.

The idea that competitive forces keep the AIs separate was the most popular scenario with 17% of the total responses. This is the idea that certain economic and political factors prevent the merger of AI, including intellectual property, AIs competing over the same market, and geopolitical competition:

For intelligence to unite it ‘they’ would need to share some common ground/common goals. I believe that is unlikely with an evolutionary driver for the development of AI. – Jay Perrett

If a general intelligence is programmed to maximize a certain function for a stakeholder, such as market value, then it might not cooperate with another AI or organization if it’s a zero-sum game. Some forms of cooperation might emerge, but they would likely only be temporary arrangements for strategic purposes.

Biological intelligence has evolved through ‘dog-eat-dog’ competitive processes. True, there has been social collaboration, but all of that was to beat out the other tribes. The same will happen with advanced AI, coalitions of machines and algorithms forming and dissolving, with and without human involvement. – Stephen L. Thaler

Another possible example that was cited was social fragmentation:

I think that a merging of AI and humans will be a cause social fragmentation of people, exacerbating the gap between rich and poor, powerful and weak; this will motivate humans who have tech to try to keep their tech separate from other tech, causing tech fragmentation and development on different platforms. – Kevin LaGrandeur

According to LaGrandeur, pressures from disparities in economic and social power might result in fragmentation, including from other forms of technology. This sort of trend can be seen today to some degree, such as tensions between the US and China over intellectual property theft and the 5G rollout, international disagreements over the rules of cyberspace and information sovereignty and possible internet balkanization, and the American public’s distrust of Silicon Valley tech companies. It’s conceivable that international and domestic fragmentation might create standards and networks of technology that are separate for another.

Some of our experts also believe that it would be difficult for AIs from other nations to cooperate, especially if they are tied to their respective militaries:

Human organizations are already meta-human intelligence, and super-intelligent machines are likely to reflect, or be part of, and hopefully be controlled by, big organizations like governments and corporations. It seems unlikely that a Chinese government AI would merge with a Google AI or Russian AI. So a multipolar world seems more likely.”– James J Hughes

The communication without merging scenario, which tied for second place at 13%, is one possible scenario where the AIs may not merge, but also might not compete or at least allow for positive-sum games where every party benefits.

Independent intelligent entities have always connected and communicated with others but have also always maintained their individuality. I see no special reason why intelligent computers would seek to do otherwise. – Daniel Berleant

Businesses and nations regularly cooperate with one another on a variety of issues, and even those that are not “friends” can often reach some form of equilibria. Some prominent examples of this would include the Peace of Westphalia, which largely brought stability to Europe after decades of war, and the mutually assured destruction (MAD) doctrine, which prevented total annihilation during the Cold War.

But coordination is also difficult:

The world has always been fragmented, because coordination is just very hard. Even though civilization slowly learns how to better coordinate, that won’t happen fast enough for AIs to easily coordinate at a global scale. – Robin Hanson

Even with complex governance arrangements, governance among humans can be a difficult endeavor, especially on a global scale. Perverse incentives, wicked problems, and other coordination problems like Rousseau’s stag hunt often lead to suboptimal outcomes. Issues of multi-agent cooperation for common-pool resources are being explored by organizations like DeepMind, which show promise for the future.

The other spectrum of answers was due to either the technical limitations of AI or because having a polycentric network of AIs is more efficient than one powerful AI:

AI has always been about building specialized intelligences. If we want [to] build [a] program to handicap horse races it [would] have to know a lot about horse racing. While some of that knowledge might apply to learning how to create and run a business for example, most would not. – Roger Schank

The first problem is that artificial general intelligence might just be too difficult to build:

General intelligence is a hard problem. Humans will likely remain unsurpassed as general intelligences while specialized algorithms will become (or already are) superior in many fields. There is no reason to believe that knowledge/expertise in one area will easily transfer to others. – Andras Kornai

It has yet to be determined if current methods of machine learning can scale to general intelligence. Some, like Roman Yampolskiy, believe that a neural net the size of the brain is all that’s needed. But others would argue that there needs to be some fundamental breakthroughs in AI before general intelligence is viable.

AI systems will become not only quicker but also better than humans at solving different problems presented to them independently… However, I believe that being able to solve “any” problem given to one AI system is a task that will require many breakthroughs in AI research. – Miguel Martinez

The other problem is that even if general intelligence is possible, it still might be more economically efficient to not pursue it and further develop narrow AI systems.

The key issue is that there is nothing special or general about human intelligence. It is only one direction out of infinitely many. Machines will develop in various directions within the space of those infinitely many, depending on our needs and market forces. – Danko Nikolic

Since humans are already generally intelligent, it might be possible that humans may never be fully automated out of production and world affairs. Market forces might push for more powerful AI tools that are compatible with human intelligence instead.

Or, it could just be impossible:

Logically there is no single unified system to answer every question. – Alex Lu

However, this does not have to be a permanent state of affairs:

Fragmentation will occur as an increasingly broader spectrum of problem formulations is generated for which increasingly diverse artificial intelligence approaches will be found to successfully provide solutions. Eventually, unification may emerge as… encompassing solution approaches are identified. – Charles H. Martin

It’s possible that as AI develops and becomes more intelligent, a wider range of possible solutions are identified in which AIs that were previously separate could integrate.

In the same way that AlphaGo discovered “creative” new moves in Go, general intelligences could also explore a wider set of cooperative strategies that allow for unification or cooperation. Advances in AI could also allow for the combination of different narrow AI applications, combining narrow and general intelligences.

Improvement of the technology leads to putting all the pieces together. – Peter Boltuc

United Post-Human Intelligence Scenario

The unification of intelligence means that one AI or system of AIs with complimentary goals has the decisive advantage in the world’s affairs. This singleton could effectively control world affairs through the application of its intelligence, as opposed to a fragmented scenario, where there is effective competition between different individual or coalitions of AIs. Uniting scenarios represented 21% of all responses.

The responses can be divided into two camps. The first is cooperative unification, where AIs merge because it’s either the best path to general intelligence or because sharing resources is an optimal arrangement. The other is non-cooperative unification, where winner-takes-all dynamics are at play.

In the cooperative unification scenario, it’s better for all the agents to cooperate with one another:

Convergence to optimal algorithms and shared datasets will lead to a unified superintelligence.– Roman Yampolskiy

In other words, having open access to data and code might be a positive-sum relationship. Open-source commons such as Wikipedia and Github both exist because knowledge and data are non-excludable goods. Unlike other goods, if two AIs exchange data-sets, each one has two data-sets instead of one. This dynamic might allow for the faster growth of AI software and for collaboration.

Another reason why AIs might cooperatively unify is because unification could be a more stable arrangement:

Fragmentation is chaos and ever increasing entropy; intelligent system would want to manage resources efficiently, reduce entropy, establish order, increase stability. – Igor Baikalov

Two or more AIs may possibly merge to form a single agent if it would help prevent defection if they come to some cooperative arrangement. In the prisoner’s dilemma for example, each prisoner makes a sub-optimal decision because neither one can affect the choice of their partner in crime. But, if both of them were essentially the same person, the dilemma no longer exists.

The other group of responses fall under non-cooperative unification:

Market forces that are trying to democratize data are far behind what is likely to be a centralized winner-takes-all data hub. I see market forces dictating the failure of small companies, leaving only large companies to play. – Eyal Amir

This scenario is more pessimistic about open-access resources being available for other actors to keep up with a handful of oligopolistic technology companies. Because certain companies are in a position to generate massive amounts of data that’s key to their business models, they’re incentivized to exclude it from everyone else to maintain their competitive edge.

This is in part exacerbated by the economic qualities of information technology. In The Second Machine Age by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, the authors point out that many information technology companies have a winner-takes-all effect in their markets, since IT services such as these have a near zero marginal-cost and network effect. For example, no other general search engine can compete with Google (except inside the Firewall of China), and Uber and Lyft are the only competitors in the ride-hailing app market.

One more person downloading something off an app store does not create a substantial production cost for that extra person. This means that an app or service that is slightly better than any other will dominate the market. Companies like these, which exclude their data to further improve their services, now have more training data to develop AI applications than anyone else. For example, services like Google and Alibaba have been able to leverage their data to significantly increase ad revenue by .

This winner-takes-all dynamic could also apply to the power that general intelligences have. It’s not clear if a slightly more intelligent agent could overpower and gain a decisive advantage against a slightly less intelligent agent. This of course assumes that the two agents are similar in intelligence.

Different singularity scenarios will likely have differences in the differentiation between other intelligences. In an intelligence creep scenario for example, it’s possible that different developers could have intelligences that are only marginally different from one another.

In contrast, in an intelligence explosion scenario, it’s likely that the front-runner will be considerably ahead of the laggards. In this case, it’s more likely that intelligence would have the advantage over others, and gains from cooperation would be smaller.

Neither or Both

It’s entirely possible that neither or both scenarios could occur. The two main types of responses where that both uniting and fragmenting would be normal and that the respondents simply can’t tell.

It’s entirely possible that different AIs will merge and split based on the goals of the AI:

AI will both fragment and unite. These processes, which are apparent in today’s world, will increase in their velocity. There will probably not be a winning process. – Tijn van der Zant

This would make sense from an optimizing-agent point of view. Different agents might decide it’s best to merge in certain situations temporarily to achieve certain objectives and then split again.

However, many of our respondents simply didn’t know.

I don’t know the answer… The complexity of AI is way above our ability to predict this; we should really consider all of these scenarios and more as possible. – Michael Bukatin

Analysis

In this section, we will be going more in-depth in an analysis of the answers that were given. We looked at commonalities and trends in the data that were not covered in previous sections, such as the relationships between different responses, to gain more insight into the future of AI.

The Relationship Between Year and Fragmentation

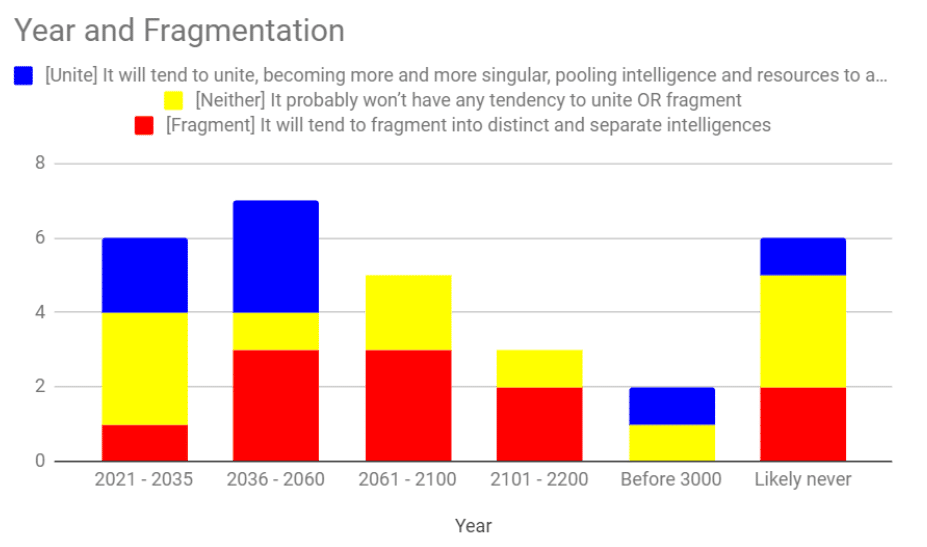

There are also variations in the date when it comes to the fragmented and united groups. Below is a distribution showing this:

Unification scenarios seem to be mostly in the near-to-medium term, whereas the distribution of fragmented scenarios is more evenly spread with more weight in the medium-to-long term. The “neither” or “both” scenario is also evenly spread out, with more weight in the near-term than the likely never scenario.

We are not sure of why the united scenarios are distributed the way they are (mostly leaning towards the near-term), but it’s clear that our respondents believe that the forces that pull AIs together into a single entity will have a strong influence in the near term or that the discontinuous jump in intelligence necessary to reach the singularity in the near term will give it a decisive advantage against other intelligences.

Respondents with a vision of united post-human intelligence might also happen to be the most optimistic about achieving AGI in the near term:

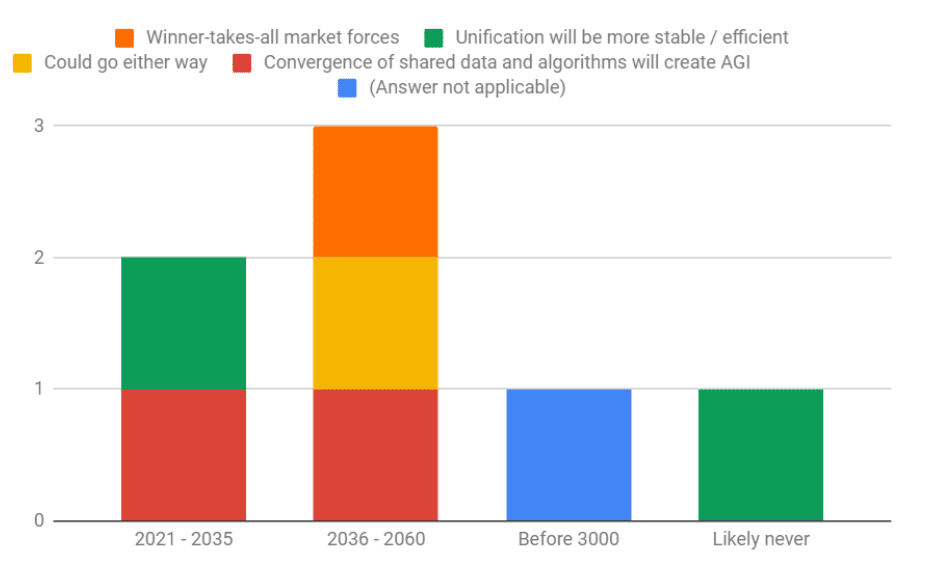

However, the data does show cooperative unification happening faster than non-cooperative “winner-takes-all” unification. The graph shows that the specific answers given for between 2021-2035 are scenarios where cooperation is more advantageous, while the winner-takes-all market forces comes after. There is a limit however to our insights because of the low sample-size, and should be further explored in the future.

United-Fragmented Intelligences Within Singularity Scenarios

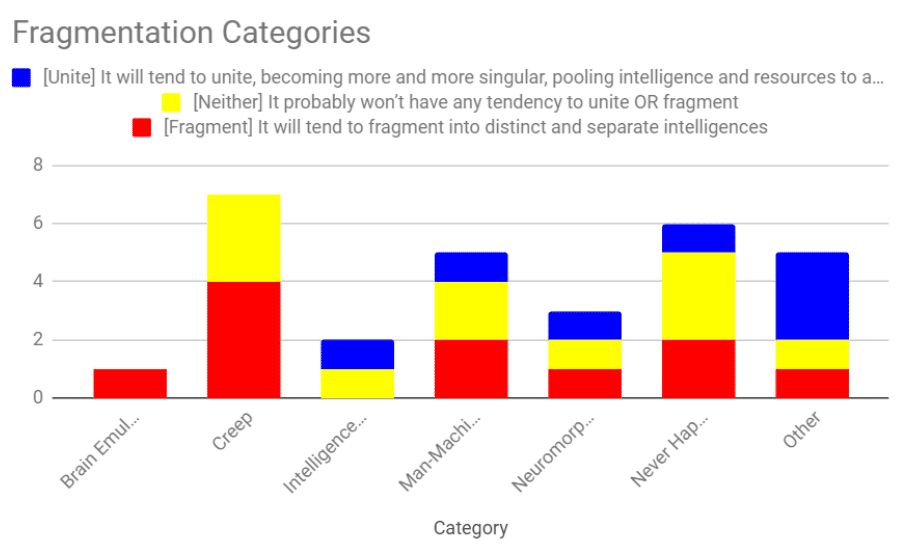

From our analysis, all united-fragmentation scenarios had some distribution across the different singularity categories, although not all were equal.

The intelligence creep scenario had the most for “fragmented,” with a substantial number of “neither or both” choices. It did not have any united responses.

This would make sense because the intelligence creep scenario would likely be multipolar, with many groups developing AI across a variety of domains, or steadily improving their general intelligence. This slow growth allows for groups to be competitive with one another, to adapt and change institutions, create rules and procedures regarding its use, and to uphold property rights.

There are some of our respondents who believe it could go either way, with the potential for these intelligences to form some equilibria or unite if they expect it to be an optimal solution.

The rest of the scenarios have a fairly even distribution of united-fragmented responses, with the exception of brain emulations and intelligence explosions, which are too small to derive insights from.