At a recent United Nations conference in Shanghai I discussed critical topics on the Chinese AI ecosystem. This article clearly and elaborately outlines perspectives on the strengths and weaknesses of the Chinese AI ecosystem, based on my interviews and discussions with various Chinese NGOs, founders, and investors.

China is now widely considered the second largest AI economy, lagging only behind the U.S., in terms of the number of AI companies and talent pool. Data and reports backing up this perception are shared throughout this article.

Further, this article aims to address the following questions with respect to the Chinese AI ecosystem:

- What is the AI ecosystem like in China?

- How do the Chinese government, private organizations, and academia alike practically work in tandem to achieve China’s AI goals?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of China’s AI ecosystem?

- What are the major similarities and differences between the U.S. and China’s AI ecosystems?

I met and interviewed several important Chinese AI leaders who are changing the AI ecosystems of the U.S. and China alike. This article includes several direct and edited quotes from these leaders throughout the article to give you a more credible and practical version of what constitutes the world’s second largest AI ecosystem.

This article is categorically divided into four parts:

- Recent History of AI in China – China’s recent AI plans, important announcements and policies regarding AI investment and funding, execution of said policies, etc.

- Strengths of the Chinese AI Ecosystem – Government’s top-down approach to the proliferation of AI, availability and easy access to a huge amount of consumer data, closed-loop ecosystem, and aggressive investment and funding in domestic and foreign AI companies.

- Weaknesses of the Chinese AI Ecosystem – Domestic AI talent shortage, relaxed data privacy policies, brutal internal market and foreign competition, and irregular distribution of funds across important sectors.

- International AI Competition Between China and the U.S. – Inarguably the world’s greatest economic powers, there is tension in talent, tech, and regulation to see who can develop AI to win the rest of the 21st century.

Without further ado, let’s take a deep dive into the Chinese AI ecosystem, starting with its recent history in introducing new plans to proliferate AI.

Recent History of AI in China

In 2016, the Chinese government made a commitment in its Three-Year Guidance for Internet Plus Artificial Intelligence Plan (2016-2018) that it would focus on funding and development of AI for improving its economy.

The July 2017 New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan released by The State Council of China details China’s strategy to build a $150 billion national AI industry in the near future, on its way to becoming the leading AI superpower by 2030. This focus on AI as a national goal seems to be a continuation of the 13th Five-Year Plan and the “Made in China 2025” industry plan. A more comprehensive version of these plans is depicted in the next section of this article.

The Three-Year Action Plan for Promoting Development of a New Generation Artificial Intelligence Industry (2018–2020) delivered on the promise of its predecessor (focusing on AI as a national priority). It outlines major areas for China to focus on with regards to AI development and proliferation. It mentions specific industries and sub-technologies that fall under AI and plans to implement a conducive infrastructure.

Some of the industries, technologies, and products China wants to focus on are:

- Integrated intelligent systems: networked vehicles, service robots, drones, medical image-assisted diagnosis systems, video image identification systems, voice interaction systems, translation systems, and smart home products.

- Smart consolidation of software and hardware: sensors, neural network chips, open source platform, etc.

- Intelligent manufacturing and industrial support resource pool, standard testing and intellectual property service platform, intelligent network infrastructure, network security and other industrial public support systems to improve the artificial intelligence development environment.

Local governments are active participants in enforcing this national goal. The Shanghai and Beijing governments also announced their implementation plans and a major AI-themed industrial environment in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Many other districts have promised funds for AI research, including Guangzhou, which founded an International Institute of AI.

Wan Gang, Minister of Science and Technology, promised at a March 2018 press conference that China would publish further detailed guidelines and policies on AI. These policies would provide directives to problems in national security, health, job structure, general security and personal privacy.

A Succinct Look at the Chinese AI Strategy

Jeffrey Ding, the China Lead for the Governance of AI Program at Oxford University, provides a succinct version of the Chinese AI strategy in his 2018 Deciphering China’s AI Dream paper:

- By 2020, China’s core AI industry gross output and AI-related industry gross output would exceed $22.5 billion and $150.8 billion, respectively, putting China in the league of most advanced countries.

- By 2025, China plans to reach core AI and AI-related industry gross outputs exceeding $60.3 billion and $754 billion, respectively, making China a global leader in many AI domains.

- By 2030, China seeks to become “the world’s primary AI innovation center,” with a core AI and AI-related gross outputs exceeding $150.8 billion and $1.5 trillion, respectively.

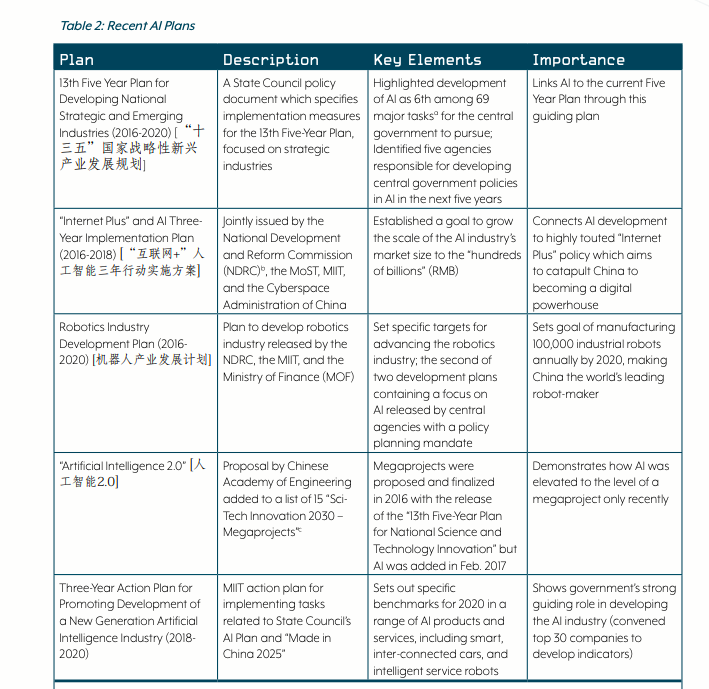

For a further understanding of the Chinese AI strategy, the table below sourced from the same paper outlines each of China’s AI plans, its driving factor and value:

Wrapping up on China’s careful plans to proliferate the implementation and usage of AI, we move on to sensitive indicators on how this might actually be possible, potential factors that might prevent China from achieving this goal, and its competition with the U.S. AI ecosystem.

Strengths of the AI Ecosystem in China

China is catching up fast with the U.S. in the AI superpower race.

A conducive factor propelling China forward in this direction is the cooperation between the Chinese government, the private sector, investors, and academia. This encourages multiple players to act toward one goal, constituting one seemingly impermeable ecosystem, which many consider to be closed-loop.

They also have the largest consumer database at their disposal, thanks to their population size and increasing numbers of digitally connected users. It also doesn’t hurt that this connected user base is amenable to sharing data. China has started to take advantage of these factors to aggressively fund and invest in AI technologies both nationally and globally, especially in the U.S.

In this section, we cover the strengths of the Chinese AI ecosystem in detail:

The Chinese Government’s “Top-down Approach” for National AI Goals

Irakli Beridze, Head of the Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, United Nations, puts it succinctly in our interview with him from early 2019:

China’s biggest strength is that the government, private sector, and academia are working hand-in-hand to achieve this [national AI] goal.

He further expands on this, stating that China is currently the world’s second largest economy, and one of the first countries to announce a national AI strategy, which they did in 2016. In 2017, they declared their ambition to “take over the world” with this [AI] technology, according to Beridze.

Beridze believes that the Chinese national AI and investment strategies facilitate execution of this goal. As mentioned earlier in the article, China has a large population of curious, connected users. Therefore, the country can acquire and analyze large volumes of big data to further its AI goals.

Kai-Fu Lee, former President of Google China, offers his perspectives in a Wharton interview on whether China will be the next AI superpower:

The Chinese government is very supportive of AI. Last July [2017], it declared AI to be one of the most important areas to focus on. Provincial and city governments are building out cities the size of Chicago with autonomous vehicles in mind. There are two layers of roads. One layer is for pedestrians and the second is for cars, thereby limiting the possible accidents and casualties to the pedestrians. Highways are adding sensors to enable autonomous vehicles. These high-spend infrastructure projects are just what the AI industry needs because private companies can’t possibly afford to build cities and highways.

Yiwen Huang, founder and CEO, R2.ai Inc shares Lee’s and Beridze’s perspectives. He was schooled in the U.S. and went back to China to found R2.ai, an AutoML company. We explored his perspectives on both the U.S. and Chinese AI ecosystems.

Huang explains that there is indeed heavy government support for AI in China. Different policies are being executed by the local and central governments to attract the right AI talent and projects. They also find AI projects and have tax policies that benefit technology companies developing or adopting AI. There is definitely a top-down AI atmosphere in China, in his opinion.

These policies seem to create an AI-conducive micro-ecosystem with more access to government, funding, and investor support and incentives when it comes to developing innovative AI products.

Ding’s “Deciphering China’s AI Dream” paper claims that the Chinese government actively picks winners in the AI space. According to this paper, the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (MoST) appointed the four largest Chinese AI companies—Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and iFlyTek—to “lead the development of national AI innovation platforms in self-driving cars, smart cities, computer vision for medical diagnosis, and voice intelligence, respectively.”

Investment and Funding for AI

Ding observes in his paper that the Chinese government is beginning to play a larger role in funding AI ventures. “Disbursing funds through ‘government guidance funds’ (GGF) set up by local governments and state-owned companies, the government has invested more than USD 1 billion on domestic startups,” he says.

According to this paper, statistics from Sun Hung Kai Financial indicate that these GGFs are projected to eclipse China’s private VC funds in size. In 2016, the fundraising target set by the government was $500 billion as opposed to the $330 billion target raised by private funds.

His paper also quotes a 2017 report which states that Chinese AI companies received about 69% of investments, whereas U.S. AI companies could only muster about 51%. Ding also notes that the velocity of AI investment is relatively fast in China. According to the paper, the average time for Chinese companies, from incorporation to receiving angel investment, is 9.73 months, compared to the average time of 14.82 months for US companies.

Beridze gives us more insights on this. In his opinion, the U.S. has more of a talent pool than China and more leading technological institutions. He says:

In China, they are also trying to attract talent from different parts of the world. Their [private sector] companies and institutions alike are issuing scholarships and competitive salary packages for western expertise to come and work on the development of AI. They are working on retention of existing Chinese talent. This will continue.

Mike Long, the CTO of CCI- a Chinese mobile payment company with 50 Million users, conveyed a point of cultural sentiment as a strength to the Chinese AI ecosystem. He suggested competitive Chinese parenting is contributing to early investment in the household as well.

Chinese parents attach great importance to children’s education. They consider it the most important thing. Maybe this is also the impact of the sense of competition. Due to the increasing heat of AI, more parents are paying attention to it. The market responds very promptly to this signal and the AI textbooks are even now appear in kindergartens.

More Connected Users. More Data

Lee delivers insights on the data aspect of AI in China:

China has more data than anybody—and AI gets better with data. If you train an AI for, let’s say, an advertising engine or an ads-targeting engine, or a bank using AI for determining loans, the more data you have, the more accurate AI becomes. China has more users and more usage per user, because the use of digital services is pervasive. For example, China has almost no credit cards and no cash. Everyone’s using mobile pay. That’s fuel to make rocket fuel for AI to work better.

His claims are backed up by a January 2018 report released by China Internet Network Information Center, a branch of China’s Ministry of Industry and Information. According to this report, about 57.7% of its population are connected users. Over 800 million people in China are active on the internet, out of which 98% are mobile users (788 million).

More connected users means more data.

In Beridze’s paraphrased words, more people are using AI, especially in the coastal regions. China has astronomically more number of connected users (people who use mobile phones, internet, etc.) and boasts a fast growth in online adoption period. WeChat alone has 1 billion users. There is a huge scope for big data analysis, owing to the company’s powerful computing power.

Huang claims that security and crime prevention sectors are increasingly using big data, which encourages the development of more new AI business models.

Openness to Sharing Data, Domestically

Stephen Ibaraki, serial entrepreneur and venture capitalist, also agrees with Huang and Beridze. In his opinion, more open policies are being made available in China for easy use and access to data. They are used in a way that speeds up innovation. He is careful to mention that this is his personal experience and he views this easy availability of data as not as big a concern in China as in other parts of the world.

He also disclaims that he cannot comment on the government’s more open data availability policies. He believes that the general Chinese population is more willing to help and more amenable to sharing data for innovation than those of other countries.

Ding, in his “Deciphering China’s AI Dream” paper, notes:

Data is another important driver for AI systems because machine learning is notoriously data-hungry. Access to large quantities of data has been cited as one of the advantages for China’s AI development.” According to his paper, China does have relatively lax privacy protections and “Chinese technology giants collect vast troves of data, and sharing among government agencies and companies is common.

But this is not without the consent of the Chinese population, according to the paper. Chinese consumers, who are the source of much of this data are “early and eager tech adopters, as reflected by smartphone penetration rates across the country.”

That said, this data availability is not without a catch, it seems. China selectively shares data only domestically, and not internationally. Jeffrey discusses China’s data protectionism in his paper. He claims that China’s internet is a closed ecosystem:

The Chinese government censored and blocked Facebook and Google, thereby enabling the rise of domestic platforms like Wechat and Weibo. One can see the advantages of data protectionism for AI development. If data is a scarce resource for AI development, China could establish exclusive control over this resource for its companies and research institutes. On the other hand, if more and more data is shared across platforms and countries, other actors could benefit from global data sharing while China remains closed off.

The Weaknesses of the AI Ecosystem in China

The Chinese AI ecosystem is not without weak links.

Despite its focus on technology and cultural inclination toward education and mainstream sciences, there is a definite AI talent shortage in China. There is also heavy competition among both domestic and international companies to penetrate into or sustain in the Chinese AI ecosystem. With relatively lax data privacy policies, China raises many concerns both nationally and globally. Further, aggressive AI investments and funds don’t seem to be distributed across pressing sectors like healthcare.

In this section, we look at each of the above problems in the Chinese AI ecosystem in detail:

Talent Disparity

Talent disparity, especially in the fields of data science and AI, is a global problem. In China, however, this problem seems to be a major concern. For a country which aims to be the world’s AI superpower, shortage of AI talent is detrimental.

In his paper, Ding claims that “despite the larger pool of STEM graduates [as compared to the U.S.], China has a talent pool of around 39,000 AI researchers, less than half of the size of the U.S. pool of over 78,000 researchers.”

He also notes that a large number of universities in the U.S. are world leaders in AI research, and this, in turn, gives way to more AI experts with “multiple full cycles of projects.” He clarifies further that 50% of U.S. AI researches have more than 10 years of experience, whereas only 25% of those in China have the same.

Beridze agrees with Ding, saying that:

The USA has more talent pool, fantastic universities. In China, they are also trying to attract talent from different parts of the world. Their companies [private sectors] and institutions alike are issuing scholarships and competitive salary packages for western expertise to come and work on development of AI. They are [also] working on retention of existing Chinese talent.

Ding admits that China’s talent programs have a mixed track record. According to his report, the Thousand Talents program, otherwise known as the Recruitment Program of Global Experts, launched in 2008, “attracted the largest influx of high-quality talent within a limited timeframe (2009-2011) in all of China’s history, per data released by the Chinese Academy of Personnel Science.”

However, his paper claims that, during this time period, multiple empirical studies and recruiter interviews revealed that the program failed to retain the talent, owing to factors such as expectations of instant research results.

This report also suggests that Chinese investors are fixing this talent disparity and retention problems through talent transfers via commercial means: for example, hiring foreign AI talent to work in China by recruiting them at 70-150% of average U.S. pay, as a “shortcut to accelerate AI development.”

Further, the report affirms that the largest Chinese AI players (Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent) have set up shop in the U.S. to attract foreign talent, which seems to be working based on the following examples: Andrew Ng, former head of Google Brain, worked at Baidu for three years. Qi Lu, former executive vice president of Microsoft, served as Baidu’s Chief Operating Officer until 2018 and is currently heading Y Combinator China.

This suggests that the government, investors, and private companies are working as active AI players in harmony together to bridge the talent gap in China.

Local and International Market Competition

Having the largest population base in the world might be a driver in the Chinese AI ecosystem for gathering and analyzing big data. However, it also poses competition problems.

Lee and Beridze are of the opinion that China’s population size facilitates the development of more AI use cases. What is more convenient here is that these use cases can be tested and tweaked in short cycles, thanks to varied market expectations and landscapes. Therefore, the time to value is relatively short. However, the other side of this coin is a heavy, aggressive competition among domestic and international companies to make it in this closed ecosystem.

Zhigang Chen, Founder and Director of Healthcare Big Data Lab at Tencent, believes:

Market competition is very brutal in China. In the US, there is domestic competition. Big companies in China (Alibaba and Tencent) are not considered competition in the US in a lot of sectors. The Chinese market is very crowded. They have domestic and international competition.

It is evident (from data, statistics and views shared in this article) that, in a way, China is battling this international competition problem by withholding its big data from the companies outside the nation, while it is increasingly investing in AI technologies in the U.S. aggressively and closing off the nation to global brands like Facebook and Google. This automatically pushes the population to use Baidu and the like.

Lax Data Privacy Regulations

In “Deciphering China’s AI Dream” paper, Ding observes that there is a “major debate over data privacy protections” in China. According to the paper:

Companies, different levels of government, and even the general public have been active participants in this debate, which pits those advocating for greater data privacy protections against those pushing for data liberalization to benefit AI technologies.

However, he also amends that:

Recently, in January 2018, advocates for data privacy celebrated when the Chinese government released a new national standard on the protection of personal information, which contains more comprehensive and onerous requirements than even the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, per analysis by CSIS senior fellow Samm Sacks.

There seems to be a consensus among the Chinese AI leaders we interviewed that China’s data privacy laws are relatively relaxed. However, these lax regulations appear to be executed only domestically. China is more aggressive when it comes to foreign competition.

Ding further expands on this point:

“Data security concerns have motivated China’s efforts to ensure valuable data stays under the control of Chinese tech companies. In this vein, China has pushed for national standards in AI-related industries, such as cloud computing, industrial software, and big data, that differ from international standards, a move that may favor Chinese companies over foreign companies in the domestic market.”

Mike Long stressed the importance of shared knowledge going so far as to suggest China could do even more saying,

Just like the development of application depends on the development of technology, the development of technology depends on the development of scientific theory. Most players in the AI ecosystem rely on open source of several AI frameworks. Some players produce their own AI frameworks based on published papers. The open source of AI framework can greatly accelerate the development of AI and produce more and more powerful and useful AI tools and applications. If big players are trying to close their source or to protect their AI technology by patents, the development of the AI ecosystem will be slowed down. Open is very important in the AI ecosystem. Due to political reasons, the US government is trying to be more and more closed. This is not a good trend for human society. The artificial barriers by political reasons can also pose a threat to the AI ecosystem. The speed of the development of the fundamental AI technology also affects the AI ecosystem.

Irregular Distribution of Funds Across Important Sectors

When we asked Chen about forces driving AI innovation in China, he mentions, from the regulatory perspective, government involvement pushes innovation.

However, he admits that:

[Speaking] from experience, I didn’t get money from the government. They are talking a lot about AI and how to use AI to bring economy to the next level. But it will take a long time. Also, they have a lot of other sectors to focus on. Healthcare is a vulnerable position. This system is overwhelmed because of China’s aging population problem. This system must be made more efficient. The government has to invest more in healthcare. Otherwise, the government will have more problem down the road.

International Competition – China vs. The U.S.

Major themes on the international competition between China and the U.S. arose during our interviews with the AI leaders quoted in this report.

Chinese AI Expansion Is Multilateral in Multiple Domains

To Wharton’s question on what the significant difference between the Chinese and American AI ecosystems is, when it comes to their resolve about being global AI superpowers, Lee answers:

A couple of things are unique about China. First, Chinese entrepreneurs are much hungrier, they work much harder, and they are also much more tenacious. They are looking for all kinds of business models in which AI can help. AI in retail. AI in education. They are also working out operational excellence in applying AI to changing the way people eat, disrupting autonomous stores and autonomous fast food restaurants. So it’s displacing traditional industries faster.

Given that China has the largest population in the world and increasingly more connected users, this multilateral expansion is logical and opportune. There is a plethora of AI use cases in China, and the national environment conducive to AI development is taking advantage of it to stay true to their AI goals.

Beridze shared his insights on this topic:

China is no different than the other big economies in the world [for choosing to focus on multilateral AI expansion]. Sectors like healthcare, transportation and energy will be benefiting a lot. Security and law enforcement fields enjoy a great amount of AI focus.

He also gives some real-time examples:

The UAE countries, after AI funding, chose only certain strategic directions even though they are some of the wealthiest countries in the world. In countries like China, I do think they have a luxury of having a big economy. At one point, they might even become the largest economy in the world. So, they have the luxury of [branching into] many sectors and see later on which sector would be [more beneficial].

“Heavy” Companies vs. “Lightweight” Companies

In Kai-Fu Lee’s experience, “Chinese companies are better at raising large amounts of money because there’s a large market that can test ideas and scale them.” He also states that the major difference between the Chinese and the U.S. companies is that the former are willing to “go heavy.” That is, the Chinese may “build something that is incredibly messy and ugly and complex” but once it is built, “it becomes a moat around [their] business.”

Lee also believes that Chinese companies are more open to taking risks and tackling the outcomes by working harder to find viable solutions. In his words:

For example, in the U.S., we have Yelp and Groupon, very lightweight companies. In China, there is Meituan, which has built a 600,000-person delivery engine, riding electric mopeds with batteries that run out pretty quickly and have to be replaced. And yet, they run it to enable every Chinese consumer to order food on their way home and have it delivered to them by the time they reach their homes. The consumers don’t have to wait. The delivery time is 30 minutes and it costs about 70 cents. It’s the hard work that is shaving away a few cents a month, eventually getting to 70 cents per order. Then, they can break even. It is taking a large leap and a large bet and a large risk, because if they don’t succeed at 25 million orders a day, there’s a huge loss.

However, it must be noted that the business models of Yelp and Groupon are significantly different than those of Meituan. The minimum wage in China is also much lesser than that in the U.S., rendering it possible to employ a bulk, inexpensive workforce in China. This may not be viable in the U.S. for the said business model, owing to the country’s much higher cost and standard of living, compared to China.

More Aggressive AI Investments in China

Lee asserts in his Wharton interview that:

AI is also being used in a lot of white-collar job displacement, which will impact the U.S. and China equally. I think China is moving faster because entrepreneurs are emboldened by the national priority on AI, funded by larger amounts of money. They see this as the hottest area.

Ding’s paper seems to back up Lee’s claims. The paper notes that, in 2017, Chinese AI startups received 48% of global AI funding, surpassing the 38% funding for U.S. AI startups. Wuzhen Institute statistics referred to in the same report show that the investment situation in China was very different in 2016. From 2012 to 2016, according to Wuzhen Institute, Chinese AI firms received a funding of $2.6 billion, which was less than the $17.2 billion received by their American peers.

Ding observes that the proliferation of AI in China in 2017 has been “astronomical” in that China accounted for only 11.3% of global funding in 2016. He believes that China’s AI industry has significantly increased in both absolute and relative terms in the past few years.

The US Is Ahead in Core Technologies. China Excels in AI Implementation and Execution

When asked how China and the U.S measure up against each other in the AI superpower race, Lee opines that the race is an illusion and they are two parallel universes making independent progress.

However, Lee believes that “China is now taking the lead in implementation and creating value by using AI in all kinds of applications and industries.”

Huang mirrors Lee’s sentiments in his interview with us: “China is better at the AI application development side.” He further clarifies that the AI tech stack begins with AI research, data collection, data management and consolidation, and then culminates in AI development. In his opinion, the U.S. is ahead of China in the data part of the AI tech stack, especially big data platforms.

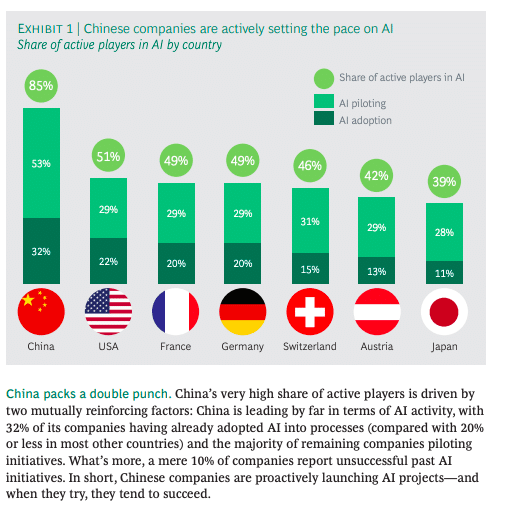

China Has a Significantly Higher Number of “Active AI Players” Than the U.S.

A 2018 Boston Consulting Group (BCG) study reports that “China is currently well ahead of the rest of the industrialized world in AI implementation, with up to 85% of companies identifiable as ‘active players’ in AI:”

According to the above statistics derived from the BCG study, the U.S. has only 51% of overall “Active Players” in AI as compared to the 85% in China. The study, however, mentions that within the Silicon Valley and digital start-up industries, this “Active AI Player” number is as much as 76%.

China’s “Technology Transfer”

In 2018, Michael Brown and Pavneet Singh of the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), a United States Department of Defense (DoD) organization that offers non-dilutive capital to organizations in exchange for commercial products that solve national defense problems, released a report called China’s Technology Transfer Strategy.

This report claims that the Chinese are heavily investing in U.S. AI companies, thereby constituting a “technology transfer” from the U.S to China.

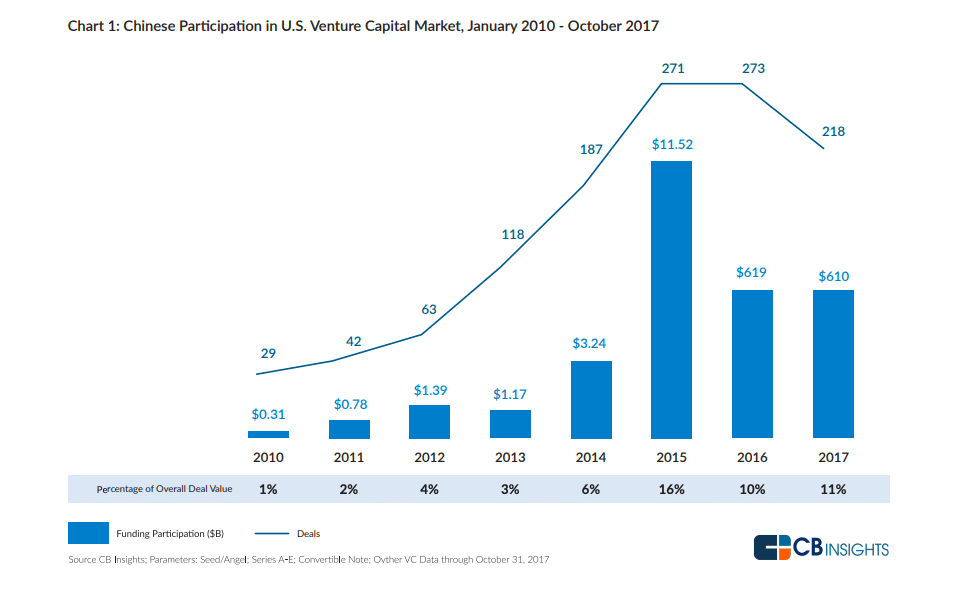

According to this report, Chinese participation in venture-backed startups constitutes 10-16% of all venture deals from 2015 to 2017.

The report further expands on the above claim to include more data. China’s rapidly growing global FDI is now ~$250 billion, with $213 billion announced acquisitions in 2016. In the same year, China also invested $45.6 billion in the U.S, where its cumulative FDI since 2000 exceeds a hundred billion USD. Particularly, electronics, information and communications technology, biotechnology, and energy sectors in the U.S. have seen $35 billion investment from China from 2006 to 2010.

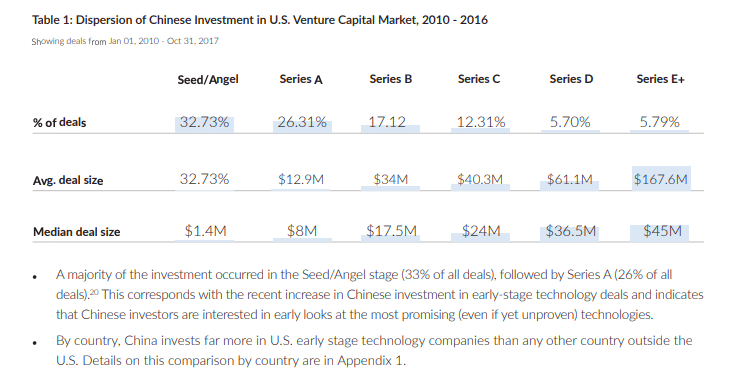

The images below, sourced from this report shows the Chinese investment in the U.S. venture capital market and the distribution of said investment across various series fundings:

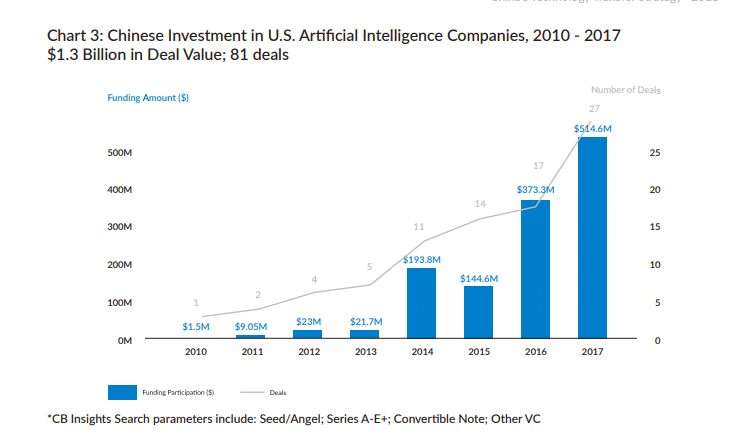

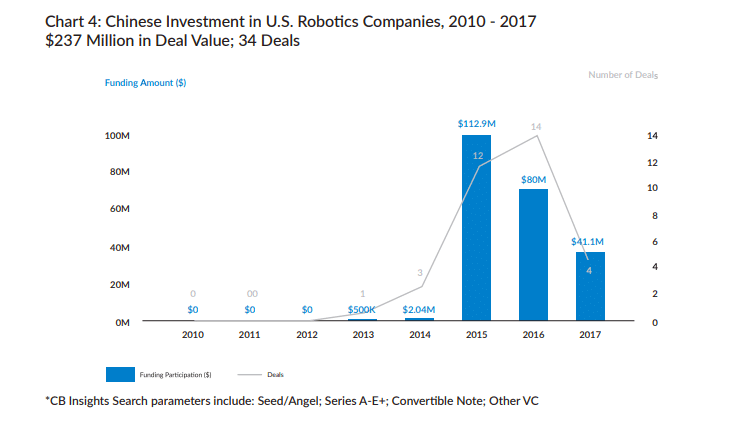

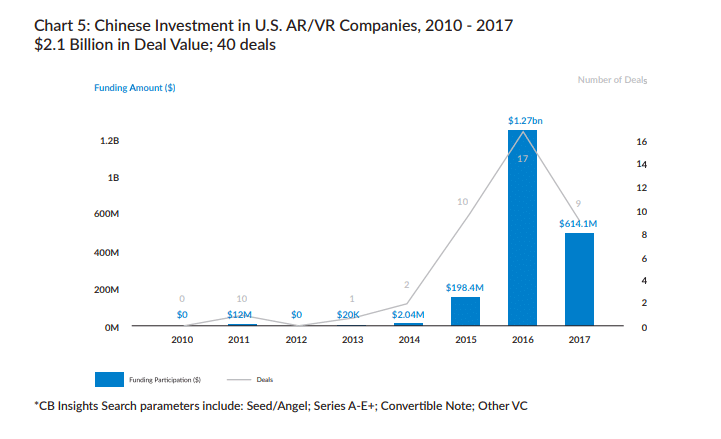

Data from the report on the Chinese investors particularly active across artificial intelligence, augmented reality/virtual reality, robotics is provided below:

Between 2010-2017, China participated in 81 AI-related funding and investment activities, contributing to a total of $1.3 billion in financing.

China has invested nearly $237 million in Robotics startups between 2010- 2017.

In the Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality space, China invested in $2.1 billion worth of deals from 2010-2017.

The report heavily warns that the U.S. needs stringent measures against the foreign transfer of domestic technical knowledge, for security and defense purposes.

Shared below is a video of Michael Brown’s interview on this topic. In this panel interview [24:30] he insists that China is catching up quickly to the U.S. in terms of economic rise with a razor focus on technology. He asserts matter-of-factly that economic security is closely tied to national security and the fact that China is aggressively focusing on technology and foreign investment funding in the U.S. is an actual threat “unlike any other we [Americans] have seen in our lifetime.”

He also notes that for the first time, another country is actually capable of being an economic competitor to the U.S. He admits that the last technology race that the U.S. had was with the Soviets. However, he is persistent that “China is potentially a much more dangerous threat” to the U.S. in the current AI race. He advises CEOs of Silicon Valley and CEOs, in general, to be more focused on this issue. He also requests for more funding for federal technology research in fields like AI, and STEM research.

Ding also mentions this technology transfer concept in his paper:

In the domain of tech transfer, Chinese firms in the pharmaceutical, biotech, and healthcare industries reached a record amount of $3.9 billion in overseas acquisitions in 2016.

Further data from Ding’s paper may also indicate why the DoD is not enthusiastic about China’s technology transfer. According to the paper, a 2017 U.S. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology report on the semiconductor industry said that China has been increasingly active in the acquisition space, while placing conditions on the access to its market for incentivizing technology transfer.

Ding’s paper also reads that, in September 2017, the White House prevented a state-backed Chinese investor from acquiring a U.S. semiconductor company, making this “only the fourth time in [the U.S.] history” for an American president to block company acquisition on national security grounds. The paper also draws parallels in Europe. When the European Union Commission introduced new frameworks screening FDI into critical technologies like “artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, technologies with potential dual-use applications, cybersecurity, space or nuclear technology,” without explicitly calling out China, analysts construed implicit references to China’s economic activities.

China’s “Copycat” Problem

While China’s Technology Transfer Strategy report clearly states its misgivings on China’s “copycat” problem backed up by data, it concedes that “there are clear examples of Chinese indigenous innovation showing that China is doing more than copying technology.”

According to the report, China leads ahead of the U.S in patent applications, academic research paper publication, and the number of STEM degree graduates. China has over 1 million patent applications, whereas the U.S. has close to 589,410. Further, in 2014, China awarded 1,288,999 STEM degrees, which is more than double the degrees awarded in the U.S.

Lee offers his opinion on why China copied U.S. technology and why it is not an IP violation:

In the beginning, a lot of American companies didn’t go to China either due to regulations that they didn’t want to accept or because they felt it was too tough a market. So the Chinese entrepreneurs started copying the American ideas. This was not IP violation, but just copying the general idea of a search engine, a portal, an e-commerce site, and so on.

He also believes that because of their growing consumer base and their entrepreneurship, the Chinese started to innovate. In the last three to five years, Lee claims that he has encountered many Chinese innovations that aren’t seen in the U.S. In his opinion, the social media for the young people in China is dominated by a video-oriented system that operates differently to Snapchat, Instagram, or Facebook. In addition, China has gradually replaced cash with credit cards and online payment systems.

Lee admits that most Silicon Valley views China as a copycat. However, he thinks it is a terrible mistake:

Every Chinese entrepreneur is learning from China and from the U.S. They religiously read all the tech media — Wired, TechCrunch, and everything. If American entrepreneurs only learn from the U.S. but not China, they’re missing out on half of the opportunities, lessons and case studies.

Finally, a comparison of the U.S. and Chinese AI ecosystems from Jeffrey Ding’s paper suggests that China is only ahead of the U.S. in the number of connected users and, by extension, data, and total global equity funding to AI startups.

However, this might be subject to change soon, given that the investment scenario in China changed in just one year, boosting China to the top in global AI funding.

Conclusion

China knows about its weaknesses in its AI ecosystem and is actively trying to remedy them with fast execution of national policies, like data and talent protection against foreign market invasion, and so on. In addition to implementing such protective measures, the country is aggressively funding foreign investments, especially in the U.S., scouting for talent and technology transfer.

The Chinese government, private companies, investors, and academia alike are working together to realize the country’s AI goals. Backed up by friendly government policies, domestic companies are enthusiastically participating in quick and short innovation cycles. Data is on the country’s side, and it seems like the country would sooner operate in a closed-off ecosystem than part with the data monopoly. This could prove powerful in as many as just a few years, as AI is still very dependent on data.

As does any large economy, China also seems to function in silos. Chen shares his experience in the Chinese healthcare sector: there is a mismatch of priorities in that the investors’ priorities are different from those of the companies in terms of objectives. He also states there is a definite gap in the expectations of people and technology limitations. There is another problem with the digitization in the healthcare sector and other sectors, which traditionally use paper-based reporting and documentation.

Despite these misgivings, he remains hopeful that China will catch up faster and more wisely as it did with its payment systems. He says:

China didn’t have electronic payment system five years ago. Credit card is the foundation for convenient payment system. When I was in China, I had to bring cash. In the last 5 years, it has changed. I haven’t used cash in a long time. I use mobile payment. In China, mobile payment hasn’t scaled as much as the US. To replace the existing infrastructure, the threshold is very high. Healthcare IT infra is not as good as in the US. So, for Chinese healthcare system to do better, it is probably easier for them to embrace new technology [than fix the old one]. New technological implementations could take off easier [in China as compared to] than the developed countries.

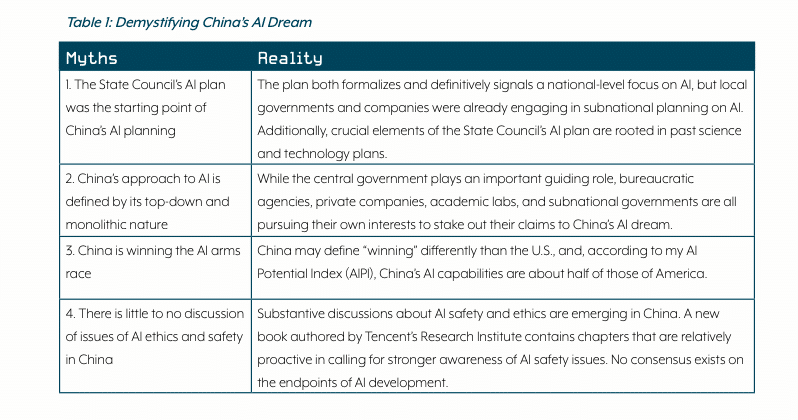

The table below, sourced from Jeffrey Ding’s “Deciphering China’s AI Dream” paper, layout perceptions vs. the reality of China’s AI policies.

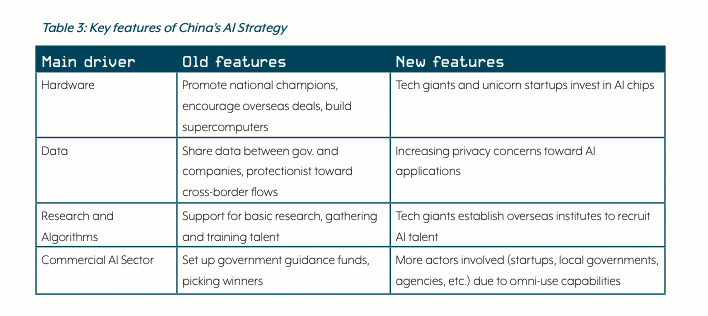

The below table is useful in understanding the new developments in China’s AI strategy as compared to the old ones:

In the above table, with respect to China’s adoption of data protectionism against foreign involvement, we hear varied opinions. Michael Brown at the DoD claims that the U.S. needs to adopt more stringent measures against China for protection of domestic technology and innovations. His views might seem extremist to some; however, there is a level of truth in the U.S. needing to invest more in AI technologies than China in order to stay ahead of the competition.

A big thank you to Radhika Madhavan for her writing and research help on this article, and extrapolating the most important points from my interviews, and from the reports and resources from Oxford, etc.