Simulation technology is the training medium of the future. Though the public view of virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) is crowded with amateur, at-home enthusiasts, VR/AR systems are being adopted by industries from aeronautics to oncology. These industries bring the reality of simulation technology closer to the public than some might realize — potentially saving lives, time, and a wealth of hassle behind the scenes.

Manufacturers have been using prototype simulation for years — uploading product designs prior to production — to save time and money. Now, industry-leaders are taking simulations one step further by applying them in training and educational settings.

AEROCAMPUS Aquitaine is an EU leader in training aeronautic maintenance staff. If that sounds so removed from your concerns that you skip to the next paragraph, consider that every time you board a plane you put faith in the technicians who’ve secured the landing gear and checked the airplane’s turbines. Technicians’ responsibilities go beyond cursory review, and encompass full repairs and maintenance of commercial, private, and military aircraft. Planes don’t yet fly themselves, and they definitely don’t yet fix themselves.

Such responsibility demands in-depth and often constant training, which proves expensive and difficult to facilitate. So, as of July 2014, AEROCAMPUS Aquitaine implemented an unconventional educational method: virtual reality.

The aeronautics training giant adopted ESI Group’s IC.IDO 10 — a virtual reality “cave” that depicts the aesthetic and function of a particular object like a car or an aircraft. The chosen object is projected to a “powerwall,” within a room in which a joystick and pair of 3D glasses provide a fully interactive, mobile, and immersive experience.

Why?

Intuitively, the best practice is performed in real time on real objects. But as any educator can attest, trainees have a habit of botching something if not everything they touch. A mistake that took a second to make could take days to fix. And maintenance staff themselves often want to experiment with new techniques, new designs and devices. Performing any of these on an already operational aircraft is risky, expensive, and ill advised.

The IC.IDO system enables trainees to make mistakes without severe real world consequences (except perhaps the loss of their job). Technicians can test a new maintenance technique without potentially severing an actual plane’s chassis. And a system that can depict whatever object is programmed allows technicians and trainees to work on the most up-to-date aircraft designs.

IC.IDO also facilitates global collaboration by connecting remote VR systems. Two trained technicians can attempt a new repair technique on a virtual aircraft from opposite sides of the globe. A professional in France can teach a trainee in China the intricacies of a complex maintenance method from thousands of miles away.

The system offers both the practical presence of a virtually realistic aircraft and the long-distance link to colleagues worldwide.

Meanwhile, biomedical engineers at Michigan Technological University (MTU) have adopted a different simulation technology to maintain an even more complex machine: the human body.

Despite awareness campaigns, breast cancer is the (poorly diagnosed) second leading cause of cancer death in women. Flawed testing methods via mammograms and subsequently false diagnoses have caused many women to undergo undue worry, expense, and additional tests.

A new examination has recently been emphasized in the clinic. Ultrasound elastography uses ultrasound images to measure stiffness of tissue. Cancer tissue is relatively stiff so the results sometimes — but not always — offer unambiguous images. In these cases, even an untrained eye could detect the cancer. But when the degree of stiffness is less apparent, accuracy of interpretation can drop from 95% to 40%!

Jingfeng Jiang, an MTU biomedical engineer, figured the biggest obstacle was lack of practice. As a postdoctoral researcher, Jiang helped develop ultrasound elastrography and noticed that the steep decline in accurate interpretations when cancerous tissue is less apparent was due to unfamiliarity with the results.

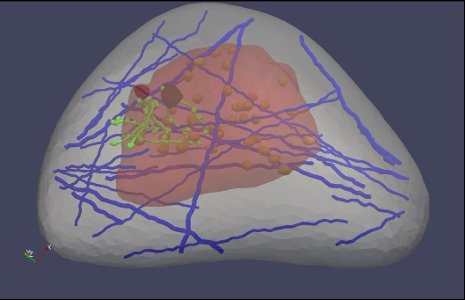

Using data from the Visible Human Project — a project that gathered thousands of cross-sectional images of human cadavers — Jiang and his team constructed a “virtual breast.” Projected as a 3D, computer-generated “phantom,” the virtual breast depicts the anatomical complexity of the real thing without the otherwise necessary human subject. A natural variety of tissue types and structures like ligaments and milk ducts are all present and controlled within a laboratory setting.

Clinicians can practice identifying breast cancer by using the ultrasound elastography on a phantom breast, and then interpreting results accordingly. No human subject is required and an incorrect diagnosis hurts no one but the clinician’s ego.

Innovations in applied simulation technology bring the reality of VR ever nearer to everyday life. Whether ensuring the skilled maintenance of an aircraft or the accurate diagnosis of breast cancer, VR is just a few degrees removed from quotidian. In training the professionals who monitor our health and safety, these simulations already benefit society from behind the scenes. And as these technologies evolve alongside other innovations — including conceptual innovations for how they may be applied — it might not be long before Ikea, Kenmore, and Chrysler send out a VR user’s manual along with their products.

Image credits: ESI-Group and Michigan Technological University