People talk with their bodies – studies show that non verbal cues account for at least half of all interpersonal communication. Some experts put that figure at 70% and even 90%. Facial expressions, posture, and physicality can deliver signs that either reinforce or undermine the verbal work going on.

This may seem like a distinctively human problem, but as people spend added time communicating with technology, some scientists have realized that verbal cues and straightforward directives like clicking and typing just don’t cut it. When conversing with Siri, half of our natural communication gestures – such as smiling, nodding, and raising eyebrows – go unnoticed. We end up inflecting synthetically, speaking like a robot as we try get our message across. Siri is meant to encourage use of natural language, but ends up complicating it instead.

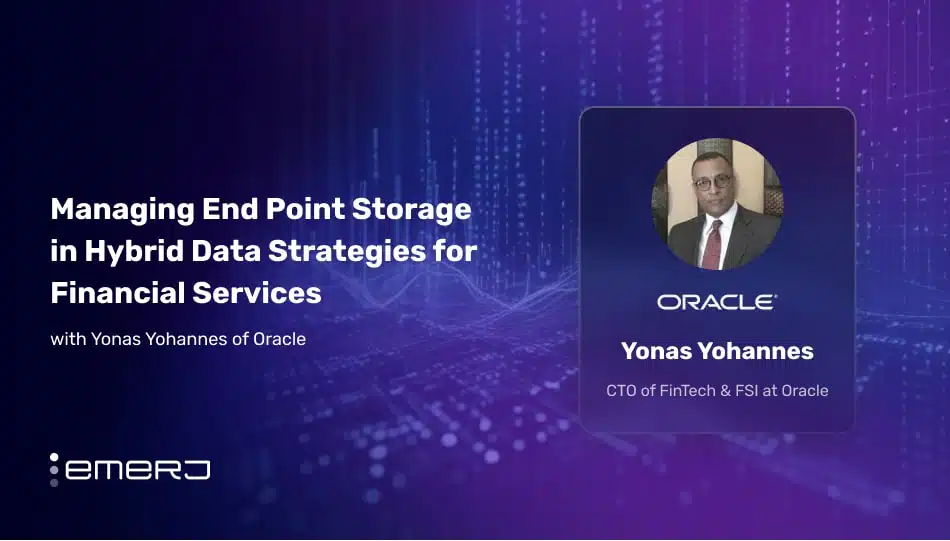

Led by Professor of Computer Science Bruce Draper, researchers at Colorado State University are developing fresh technology to help smooth communication between humans and our technological devices.

Draper notes the obvious but often unrealized fact that the very nature of our relationship with technology is evolving. Whereas technology originated as tools to be used, devices have become things which assist both in performing a task and providing feedback and guidance. You’d never ask a hammer how to hit a nail – but you would ask Google maps for the quickest route home. You may even then give feedback to Google maps, adding a note that there’s road work on this street or bad traffic on that. What was once a one-way conversation is now a feedback loop. In this sense technological devices have transcended their role as basic tools to function and have become something of counterparts that we engage with bi-directionally.

“First, they provide essentially one-way communication: users tell the computer what to do,” says Draper. “This was fine when computers were crude tools, but more and more, computers are becoming our partners and assistants in complex tasks. Communication with computers needs to become a two-way dialogue.”

Backed by a recent $2.1 million grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), Draper’s project – dubbed “Communication Through Gestures, Expression and Shared Perception” – is set to revolutionize the way we get on with computers.

In order to meet their goal, Draper and his team plan to grab information about gestures and facial expressions into a catalogue of what they call Elementary Composable Ideas (ECIs), bits of non verbal data derived from human interaction. The ECIs as a whole will be structured with a syntax-like spine that guides how the information can be read.

Draper and his team will use a Microsoft Kinect to analyze a human as she interacts with objects and other stimuli at a table. The Kinect interface records the nuances as the subject uses natural gestures – which Draper stresses is vital.

“We want people to come in and tell us what gestures are natural,” says Draper. “Then, we take those gestures and say, ‘OK, if that’s a natural gesture, how do we recognize it in real time, and what are its semantics? What roles does it play in the conversation? When do you use it? When do you not use it?’”

Scientists outside of Colorado are also making strides toward teaching robots to read language. At MIT and the University of California at Irvine, researchers used a series of instructional YouTube videos to train an algorithm to read non-verbal cues called subactions or micro-expressions. These subactions are like words and phrases in that they create a comprehensive message when added together. With these studies and more, robots may soon be able to tap into our oldest form of communication and engage with us in the most natural way.

Credit: Tracey Meagher